- Allan Rae

- Jeanne Bamberger

- Richard Wagner: Tristan and Isolde

- Schubert: Winterreise

- Ernest Berk

- Wergo

- Joseph Joachim

- Rossini: Zelmira

Memorable Voices

JEFFREY NEIL investigates San Francisco Opera's sold-out production of Georges Bizet's 'Carmen'

Six months after Bizet's premiere of Carmen in Paris, Ernest Guiraud tinkered with the orchestration of the Arlésienne suite for a Vienna Court Opera production to accommodate a ballet in the second act and transform the piece into a 'grand opera' filled with dance, lavish sets, and exotic costumes. In contrast, San Francisco Opera's sold-out Carmen this season, conducted by Benjamin Manis, fell in line with recent productions at the War Memorial Opera House, such as Tristan und Isolde, prosecuting a case for austerity that squelched the possibility of grandeur. The production was saved by the strong performances of its talented vocalists, in particular Eve-Maud Hubeaux (Carmen) and Jonathan Tetelman (Don José).

Jonathan Tetelman as Don José and Eve-Maud Hubeaux in the title role of Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Before the mise-en-scène was revealed, a burnt umber Braille curtain introduced an unrelenting visual color theme of tobacco that dominated Francesca Zambello's production for San Francisco Opera and Washington National Opera. Act I begins with a pinpoint of light at the foot of the stage that expands to reveal the blurred silhouettes of the singers behind a black scrim, a staging similar to what has been seen in Covent Garden and Oslo. Behind me, the outrage of a curmudgeon in the audience exclaiming, 'This is stupid' sums up what I think has been a persistent problem this season: the foreshortening of the possibility for transcendence and - dare I say - escapism in the 'deconstructed' staging. The sets were monotone and claustrophobic, the costumes drab, and the lighting so dim as to make it hard at times to see what was happening on stage.

A scene from Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Carmen is an opera of cultural and erotic voyeurism: sung in French, but set in Andalucía shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, the theme of occupation by a ruthless foreign force has to always be in the background. The production moves the time period to 1875 (something that only a diehard fashionista would have discerned from Carmen's bustle in the fourth act), and it is not clear what the dramaturgical pay-off was of this transposition out of the revolutionary part of the nineteenth century and into the actual year that Carmen premiered in Paris.

The spirit of revolution and bourgeois prurience animates Carmen. Carmen and her Roma companions have gun barrels trained on them, but manage to turn them around to threaten the military men and the social conventions they uphold: thus the dynamic is set between Carmen, who embodies libidinal freedom and Micaëla, an irritating evangelist of middle class propriety. For Micaëla Bizet has composed dulcet music that soprano Louise Alder sung with unflagging conviction.

Louise Alder as Micaëla in Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera.

Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

It's a sign of where we have traveled as a culture that when this throwback of feminine virtue from the Bourbon Restoration implored Don José to return home to his dying mother in Act III, the audience reacted with raucous laughter.

To understand how Carmen is linked to liberationist movements of the working class, it's worth comparing her story with that of Preciosa from Miguel de Cervantes' La Gitanilla, written two and a half centuries prior. In Cervantes' fantasy, a gypsy girl enchants - instead of ensnaring - a Spanish lad of 'clean blood'. Rather than Carmen's sultry dances that subvert bourgeois propriety, Preciosa's dances are modest, and when she is not dancing or reading fortunes to the aristocrats who are fascinated by her, she recites and astutely interprets poetry. In Cervantes' fantasy closure, the gypsy is discovered to be an old-Christian aristocrat, so there is nothing risqué when she finally marries her Don José equivalent.

Bizet's Carmen is on the surface the diametrical opposite of Cervantes' earlier vision, a product of a revolutionary Romanticism, but it is also not quite as exotic as it might seem. Carmen reflects the 'grisette' in France, whom the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française described in 1835 as 'a young working woman who is coquettish and flirtatious'. Grisettes were irresistible to young men from good families, who in real life were prone to use them and ruin them when their infatuation wore off.

Eve-Maud Hubeaux in the title role of Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Carmen, however, will not be owned - or discarded by a man. Eve-Maud Hubeaux shows how the character resists through acts as simple as casually washing her dirty leg in public while singing 'L'amour est un oiseau rebelle'. Hubeaux's nimble mezzo-soprano voice and agile movements tap into the potential of the lyrics and the music to give us a sense of freedom. This is an opera with flights of strings and wind instruments that inspire a desire to abandon duty. I felt a special thrill in the control and ease with which Hubeaux oscillated between notes in her 'Prends-garde à toi' at the end of Act I. What differentiates Carmen from the typical Parisian grisette is the danger she poses - an irresistible titillation. Even the armed man must protect himself from her.

Eve-Maud Hubeaux in the title role of

Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera.

Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

As Don José, Jonathan Tetelman looks the part, and from Act I to his effortless wails at curtain close, his vocal talent meets the challenges of the role. Don José and his rival Escamillo are the two poles of masculinity - the tenor who struggles with conventional duty to a feminine ideal and the swashbuckling toreador whose pervasive leitmotif broadcasts his celebrity. But Don José is the more complex character, embodying the Romantic ideal of devotion to love at all costs. Tetelman's voice is able to flit between sweet plaintiveness and robust lustiness to communicate his tortured devotion, epitomized in the simple question: 'Carmen, tu m'aimeras?'

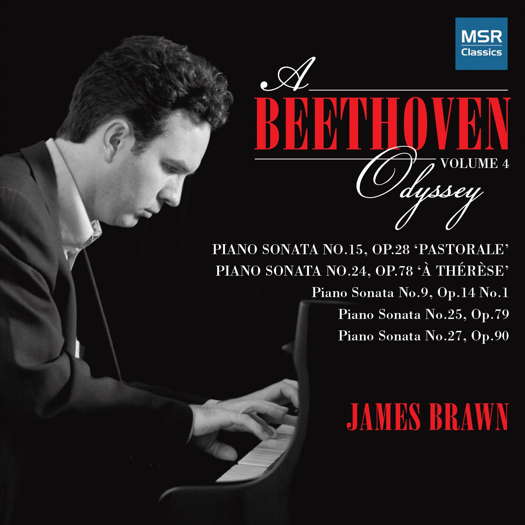

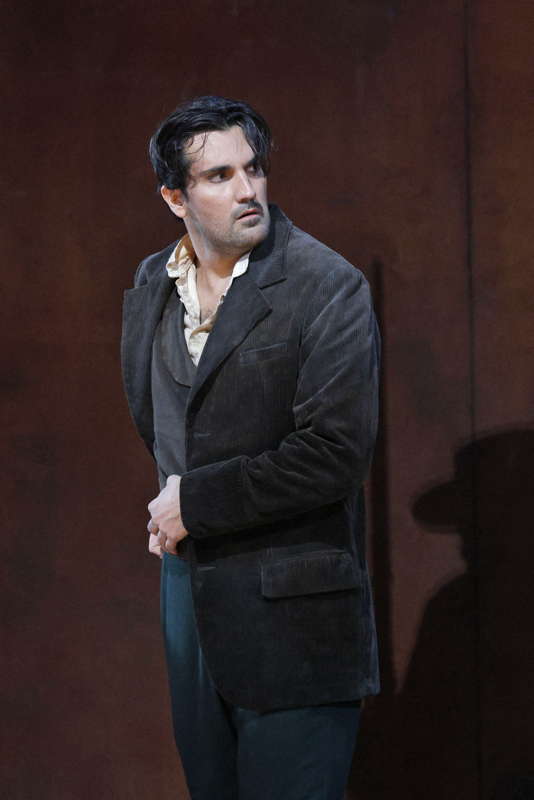

Jonathan Tetelman as Don José in

Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera.

Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

The production incorporates some dance - in Act II, the seguidilla and the closely-related sevillanas, whose movements are softer and more rounded than the ballistic and staccato moves of flamenco. The performances were graceful enough, but they would have optimally communicated the same undercurrent of desire and terror that characterizes the dynamic between the lovers. This gets us to the issue of the heat between Hubeaux's Carmen and Tetelman's Don José. The relationship is complicated, more so because of the tragic difference in expectations between them. I don't think the duo ever fully captured the manifold conflicting feelings between characters they play - Don José repeatedly asking, 'Tu es le diable?' ('You are the devil?') and Carmen expressing her need to be free from the binary of pious maiden or diabolic temptress.

As a welcome departure from the Dickensian squalor of the encampment in Act III, which featured tarps thrown over the walls of the recycled set from previous acts, Act IV introduces pageantry and color. There are dancing toreadors in splendid particolored, beaded outfits, and the reappearance of the gorgeous Drogen, a white and buff Gypsy Vanner gelding.

Christian Van Horn as Escamillo and members of the San Francisco Opera Chorus in Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Some of the newer talent, like Adler fellows bass-baritone James McCarthy (Zúñiga) and soprano Arianna Rodríguez (Frasquita), possessed some of the most memorable voices.

From left to right: Christopher Oglesby as Dancaïre, Alex Boyer as Remendado, Nikola Printz as Mercédès and Arianna Rodríguez as Frasquita in Bizet's Carmen at San Francisco Opera. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

SF Opera veteran Christian Van Horn's bass-baritone voice complemented Tetelman particularly in their Act III duet where Escamillo's vocal swagger and machismo battled the supple, full vibrato of Don José.

Variations of the phrase 'Laisse-moi' or 'Laissez-nous' ('leave me alone,' or 'let us be') appear fifteen times in the opera. I strongly believe that these deconstructed or minimalist productions simply do not free the performers to fully realize the emotional and aesthetic potential of Carmen. With so much young talent showcased in this production, it's a shame that this production was short on grandeur when it came to sets, costume, lighting and dance.

Copyright © 23 November 2024

Jeffrey Neil,

California, USA