- Kamilló Lendvay

- Ludvig Norman

- John Blackwood McEwen

- Peter G Howell

- Marco Polo

- Donizetti: Maria Stuarda

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

- Oleg Lundstrem

SPONSORED: An Integral Part - Lindsey Wallis looks forward to the Canadian Music Centre's tribute concert to composer Roberta Stephen.

SPONSORED: An Integral Part - Lindsey Wallis looks forward to the Canadian Music Centre's tribute concert to composer Roberta Stephen.

All sponsored features >>

PODCAST: Join Jenna Orkin, Maria Nockin, John Daleiden, Gerald Fenech, Julian Jacobson, Patrick Maxwell, Giuseppe Pennisi and Mike Wheeler for a fascinating fifty-minute audio only programme.

PODCAST: Join Jenna Orkin, Maria Nockin, John Daleiden, Gerald Fenech, Julian Jacobson, Patrick Maxwell, Giuseppe Pennisi and Mike Wheeler for a fascinating fifty-minute audio only programme.

Wholly Fresh Life

RODERIC DUNNETT attends two events in the UK to hear the work of Ian Venables

Two recent events, centred on Oxford and Worcester, have served yet again to confirm the extraordinary talent, freshness and originality, and deep insight of Ian Venables, one of the most intensely admired and justly acclaimed English composers at work today.

Ian Venables' preeminence in the realm of English song has long been recognised. Each new work is a revelation. Whatever the texts he chooses to set - and by now they feature many different ones, one is overjoyed to point out - at its heart is the poetry itself, and the unique skill he displays to probe and prise out from the words, so impressively, both meaning and subtext.

A portrait of Ian Venables

Time and again, a Venables setting has proved a veritable marvel, especially for the unexpected discoveries it makes: not just its extraordinary empathy with the text; but so frequently the beauty, the joy or pathos, depending on the slant of the words. Each song - or more significantly, each cycle - is an exploration, and reveals a recognisable, highly individual, vitally appealing and invariably attractive style, through which he draws the constantly absorbed listener in and personifies each stanza and paragraph of his chosen poet. Invariably, he does his authors, whether British or other - American, for instance - a special service: he illuminates them by underscoring the intention and drift of the words, exploring their undertow, artfully teasing out, capturing and encapsulating the finest detail, lending specific emphases that enhance and uplift the understanding of the listener.

It has proved doubly exciting to discover that just as Venables excels so marvellously at what is known as Art Song (Lied), he is also a fine composer in other genres. Chamber music - his Piano Quintet, for instance, and especially energised, enterprising early String Quartet but also works for solo instrument - attracted him from quite early on, and it should not be forgotten that several of his song cycles have been coloured additionally by a solo instrument - clarinet, for instance, or viola - or latterly by a select group of instruments, as in his striking latest achievement. But church music too: he has composed anthems, perfect for the forces, some of them quite dazzling; a set of Responses; and to be heard this summer, both Evening Canticles - the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis. But above all comes his shining Requiem: gorgeously expressive, and widely hailed as one of the finest - if not the finest - of present day settings of the Mass for the Dead, it is has won huge recognition for its economy, eloquent, highly sensitive word setting and pervading tenderness. The entire work is - and many take the same view of his finest song cycles - a masterpiece.

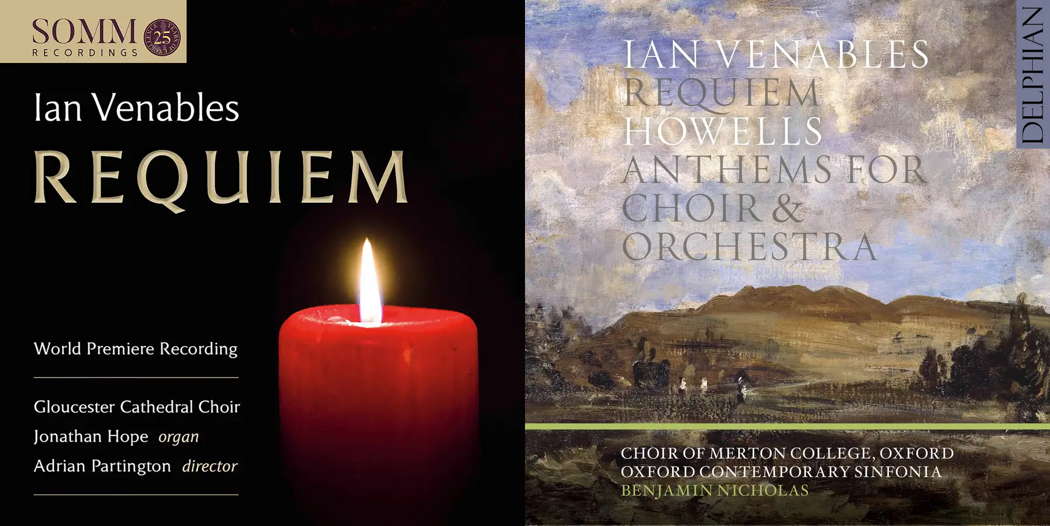

Written for the choir of Gloucester Cathedral, not only did his Requiem receive its moving, fabuously polished first performance from the cathedral choir under the direction of Adrian Partington (gorgeously recorded on the Somm Recordings label, SOMMCD 0618); but it has proved a vehicle for Venables' inspired, and to some extent unique gift for striking orchestration in the commissioned full version subsequently unveiled by the Choir of Merton College, Oxford on Delphian Records DCD 34252, conducted with equal perception and to exemplary standards by Benjamin Nicholas.

Recordings of Ian Venables' Requiem - SOMMCD 0618 (left, © 2020 Somm Recordings) and Delphian Records' DCD 34252 (© 2022 Delphian Records)

Thus exquisite, deeply thought through word setting, aided by a profound, indeed characteristically beautiful personal language, is a hallmark of everything Venables writes. His newest song cycle - he has composed nigh on a dozen - was unveiled at a very desirable venue, The Church of St John the Evangelist, in Oxford - a location which has grown to become one of the most highly valued of Oxford concert halls, with a well-attended series focusing especially but not exclusively on the piano, occasionally with solo instruments or ensembles added.

As here. Out of the Shadows, Op 55. for baritone and piano trio, is his latest arresting song cycle, written to a private commission and given its first performance in May 2024. He has turned to the Greek (Alexandrian) poet Constantine Cavafy, whose writings - he was a friend of E M Forster - express the hopes, delights, yearnings and disappointments central to his life, the great bulk of which give voice to his homosexual inclinations and remarkably open and honest expression of them for the times he lived in. There is pain; but also joy. He relished who he was, and had no wish to change.

So apt a subject is the treatment of Cavafy, possibly not for the first time, by Venables - it was clear here - that one might hope for Venables to revisit him. 'At the cafe door' is about as explicit as any Cavafy poem - redolent too of the Greek Anthology. To evoke a beautiful, presumably youthful male body, fashioned, as it were, by Love itself - Eros in his mastery, joyfully model(l)ing its well-formed limbs' - requires a subtle, painterly hand such as the exemplary, ever-precise chiselling of Venables' paintwork, abetted by his (Phoenix) piano trio, which enchants as much as the sumptuous subject himself, as alluring as Hadrian's boy-love Antinous.

The Phoenix Piano Trio

The third poem here, 'The mirror in the hall', is also by Cavafy, indeed one of his most famous, its imagery so compact, fresh, naughty and original, and like other poems in this new cycle it exemplifies par excellence the extraordinary gift Venables has for choosing texts which will respond to musical setting, and then proving with unerring expertise the rightness of his choice.

Here as usual is a young desirable again, 'a tailor's assistant'. An almost haunting quality attends the music here, and with good reason. For the third section reveals a mystery: the mirror into which this hungered-after boy looks - he is receiving payment, one might almost think for services rendered - remembers, and treasures, uniquely, 'the image of flawless beauty' that it has for a few brief moments embraced. The lingering memory of a pretty, nay exquisite, boy - or young man, depending on the poet's taste of the day - of course mirrors the recall of the viewer - the poet - himself. In Thomas Mann terms, a Death in Venice experience. To capture and embrace the magical moment cries out for beauty, and empathy, in the music, and a richness mixed with innocence, such as Venables so expertly imports here.

And these are the qualities, too, that Venables' innovation, delicacy and sensitivity inspires in his soloists, who have included those most eloquent of singers, Roderick Williams and Andrew Kennedy. Here baritone Gareth Brynmor John with marked eloquence captured the spirit of every song, lending it charm, carefully differentiating the moods particular and special to all six, weaving gorgeous expression, phenomenally rich timbres and a wealth of intelligent insights from the subtle web of Venables' writing.

Gareth Brynmor John

Another entrancing feature of the entire Out of the Shadows cycle is, of course, the trio of instrumentalists, and the range of ways Venables employs the three together, paired, or individually, to achieve maximum effect and characterise individually each song. The second poem, by Horatio Brown - 1854-1926; his collection Drift was published exactly in 1900, Venice-based, a mountaineer, and an enjoyer, indeed understanding supporter of liberal views, although a writer of homoerotic verse as only a sideline amid such wider expertise - includes in its central stanza a line 'Piano, 'cello, violin', and mixes irony with an amusing, almost Baudelairean touch in each final line, in which the same comely young man is lightheartedly celebrated. A tweaking of instrumental textures - contrasting touches of one, two or betimes all three instruments lend forward impetus to the whole - is an ideal way to capture the shifting detail of a poem such as this. Indeed it's relatively, perhaps surprisingly, rare nowadays for such cycles, Venables points out, to be accompanied by more than just piano.

Despite the thrust of the texts here the idea was not to generate a 'gay' cycle, but to celebrate love and friendship between or among men, usually patently Platonic in its day. To include - so appropriately - an extract from Tennyson's In Memoriam A.H.H. (Arthur Hallam), called forth from Venables a touching tenderness. Lines like 'A hand that can be clasped no more', so deeply tragic, or 'he is not here but far away' and the tragically resigned concluding 'blank day' illustrate marvellously the composer's gift in many of his songs - his settings of A E Housman, for example - for evoking with empathy and understanding human situations where the predominant emotion is grief.

Profound insight into the texts he sets is wholly characteristic of Venables. He has a vivid intimacy with and especial insight into the poetry of John Addington Symonds, and here has revealed another contrasting feature of his art - a flair for evoking in scherzo mode mischief, joy and fun. A typical previous example was his buoyant setting of one of his best-known flippant songs, 'The Hippo', as entertaining as Flanders and Swann.

Here the poem, 'Love's Olympian laughter' is almost outrageously happiness-filled. Venables frequently digs into his magnificent repertoire of perky good cheer to bring vividly alive phrases like 'a bat or cricket ball or racquet' (rhymed with 'flannel jacket'), visualising Love (Eros or Cupid) forsaking his bow and quiver and transmuted into the beloved youth, named 'Laurence' (just as Horatio Brown thrice declares himself enamoured of a boy 'John'). The Symonds song has bounce, and enraptured flippancy, its levity almost like naughtiness. Such a delight.

Serenity is the keynote of the sixth and last song, 'Body and Soul', by the poet Edward Perry Warren, whose dates (1860-1928), spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, virtually concide with both Brown and Cavafy's. The 'calm heaven', which Venables so aptly and incisively conjures up, folds exquisitely into 'that love can melt the body and soul in one' - worthy of a Shakespeare sonnet. Teasing out music sensitive enough to capture 'the cloudland of thine arms' and 'wherein I love thee more daily and after' - forming an exquisite envoi to this delicate and enchanting cycle - cries for the kind of expressive mastery for which Ian Venables is so widely admired. He enters every text, so often splendidly and imaginatively chosen, lends it the richness of his personal idiom, and brings to it by his perception and allure added meaning. A rare skill, so beautifully evidenced here.

This was in fact the second recent recital honouring the vocal music of Ian Venables. Shortly beforehand, his song cycle Invite to Eternity, a beautifully crafted treatment of four poems by the poet John Clare (1793-1864), took central (and pride of) place at the Royal Grammar School, Worcester in a riveting evening's appearance by the tenor Brian Thorsett, paired with the captivating Dante Quartet - Zoë Beyers and Ian Watson, Carol Ella and cellist Richard Jenkinson.

The Dante Quartet

Clare's poetry, much of it postdating his incarceration in an asylum, is wide-ranging in moods and evocative. The second poem set here - the same as the work's title - is a touching, wan, and pleading invitation to a young girl ('Say, maiden, wilt thou go with me?') - yet increasingly coloured by the ever-presence of demise and death; the third, 'Evening Bells', is a positive rejoicing - a scherzo in words as well as music, a vivid and joyous creation.

John Clare

The first here, 'Born upon an Angel's Breast', includes a marked contrast, although the mood distinctly lightens: 'The sweetest feeling of the heart - There's pleasure even in its smart ...'. There is also a tinge of violence that is intense and disturbing, evoking the flavour of the tragic depressions which led Clare to be incarcerated in an asylum, or asyla, from his late forties till his death. The splendidly expressive tenor, Brian Thorsett, dived deep into the texts to bring a riveting directness and enthralling clear diction to each line, exploring with the strings - second violin and viola, for instance - a wealth of varied expression.

There are so many ways in which Venables achieves enchanting and desirable effect: in the four-stanza second song, the expressive power of his setting at 'to see things pass like shadows ...', the subtle way in which he capitalises on the poems' technique of enjambment to make successive lines embrace and coalesce; the different means by which he keeps poem and music alike moving; touching apoggiaturas that perennially decorate the evolving lines; delicious exchanges between individuals - second violin (Ian Watson) and viola (Carol Ella), or others, or the sensitive, fusing way in which the song settles on its conclusion. ('Then trace thy footsteps on with me; We're wed to one eternity'.)

The third song illustrates wonderfully Venables' skill, as so often, in saying something in a way one might not expect; often, he captivatingly springs surprises, and each delicious surprise brings with it a kind of glee. He squeezes more out of a phrase than one would ever think possible: the rewards are great. The most poignant John Clare poem, Ian Venables reserves for last: tragically entitled just 'I am'. The deeply emotive cello opening, slow, tender yet also gradually declamatory; a certain starkness - what could be more apt? Knotty entwinings for the full quartet - one thinks of Schubert's Quartettsatz - as the writing for the voice, enunciated with such delightful eloquence and finesse by Brian Thorsett, pursues its course, the more despairing or embittered ('I am the self-consumer of my woes'), the pained 'nothingness of scorn and noise', or 'the vast shipwreck of my life's esteems' yielding to the serene and dreamlike 'And sleep as I in childhood ... Untroubling, and untroubled where I lie'.

Venables' fine achievements in the field of chamber music, with or without a vocal part attached, are well known and highly valued. Furthermore, his dedication to the cause of the composer-poet Ivor Gurney (1890-1937) has had a magnificent impact on the good fortunes of that most gifted, both elated and poignant Gloucestershire song composer. It is owed not a little to Venables and the hands-on Gurney Trust he so considerately chairs and leads that the modest number of recorded Gurney songs has blossomed and wonderful fresh riches have been unveiled.

Ivor Gurney

Venables' gift for handling chamber forces in such a way as to further enhance and enrich the feeling of the poetry he sets has been long recognised: his cycle The Song of the Severn, premiered at Malvern in 2012, showed his unassailable gift for evoking rural-inspired poetry by John Masefield and others. In his treatment of poetry by Andrew Motion, Remember This, his use of piano quintet served at every point to underline some phrase or individual word to which he felt due attention should be drawn. His recent masterpiece, Portraits of the Mind, commissioned by the Vaughan Williams Trust and featuring not least an evocative poem by George Meredith, exemplifies yet further not just Venables' deep perception of the relation between music and text, that of a true professional, but his astuteness for exploring how a small ensemble by its range and often, in his case, innovation, can provide further insight and tease out reflective undercurrents that might in a blander treatment be virtually missed.

The idea of arranging four of Ivor Gurney's songs for tenor and piano quintet was not just an inspired one, but one which, to quote words from the powerful opening song, 'opens unknown doors'. Certainly, Venables' arrangements shine fresh light, as he always does, and intensify each passage of text before him. Herbert Howells, even during the Great War, had orchestrated two Gurney songs, including ('By a Bierside') and Venables had already orchestrated two more, including the powerful and resigned last poem of Sir Philip Sidney, 'Even such is Time'.

Certainly from his five instrumentalists he does not shrink to evoke at key moments massive power - 'Death is so blind and dumb ...', the quintet soaring to great heights. Yet from song to song, he most inventively and meticulously invites from his players and the soloist an array of ever-shifting moods, just as Gurney does. One great gift of these incisive settings is that he also, as mentioned, has a gift for avoiding the obvious. At the end of 'By a Bierside', as also in the beautifully nostalgic 'In Flanders' (really meaning in Malverns) he draws out an immensely expressive section pianissimo; contrasted with the usual buoyancy, indeed rapture, the former ends with not so much merry bravado - the penultimate 'Cotswold or Malvern' - as intimacy: Richard Jenkinson's exquisite cello ending hangs in the air, enraptured, beautifully becalmed and becalming.

These fine, profoundly imaginative details, of dynamic as well as colour, often betraying a degree of marked originality, are what give Venables' handling of Gurney here its welcome added new dimension. Again it is the cello which captures so specially purely Gurney's achingly beautiful short phrases - as polished as a haiku - in his own poem 'Severn Meadows'. The cello hands up to lead violin, thence the melody is shared around, and from the final line Venables draws out an utterly melting envoi. From Edward Thomas' 'Lights Out', Gurney prises a song which can be most justly compared to perhaps his supreme masterpiece, 'Sleep', from his prewar Elizabethan Songs. With piano alone it is a marvel. One element of Thomas' in themselves almost somnolent three stanzas which is captured so entrancingly by not just Gurney but by Venables too with his subtle manipulation of strings and keyboard, is the enjambment: we are lured on by the instruments: 'Unfathomable deep/ Forest' ... 'Straight/ Or winding' ... 'dearest look/ That I would not ...'. The lines weave into one another and are enmeshed with the utmost finesse, as almost gossamer tendrils. Thomas, Gurney, and Venables.

Ian Venables. Photo © Anthony Cheng

The first sows the seed, the second finds shape, the last gives it wholly fresh life.

Copyright © 4 June 2024

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK