DISCUSSION: Defining Our Field - what is 'classical music' to us, why are we involved and what can we learn from our differences? Read John Dante Prevedini's essay, watch the panel discussion and make your own comments.

DISCUSSION: Defining Our Field - what is 'classical music' to us, why are we involved and what can we learn from our differences? Read John Dante Prevedini's essay, watch the panel discussion and make your own comments.

Peace comes dropping slow

I recently listened to a soprano saying with polite exasperation how that when people find out she is a musician they typically ask her what instrument she plays. When she informs them that she sings they typically respond 'ah but that's not an instrument'. The veracity and tact of this statement are inversely proportional to the ignorance from whence it oozed. For anyone out there who thinks the human voice is not an instrument, I would ask you to ask yourselves why do all professional and many amateur singers spend decades training their larynxes, diaphragms and lungs. Not to mention investing so much time and effort in the ability to reproduce, with precision, what are oftentimes enormously complex vocal scores. On top of this the far more nebulous art of interpretation requires as much dedication and study as any singer has at their disposal. Why do trained singers even in the world's largest opera theatres not need artificial amplification to make every note they emit perfectly audible? Artificial amplification that it seems not even buskers can dispense with these days.

The human voice in its fundamental role in not only the Western classical tradition from Gregorian chant on but also in so many ancient and vigorous indigenous musical traditions from around the world is arguably the greatest of all musical instruments and when trained can produce music unlike anything else in the universe. With that humble introduction here are a few pieces that showcase the word made flesh.

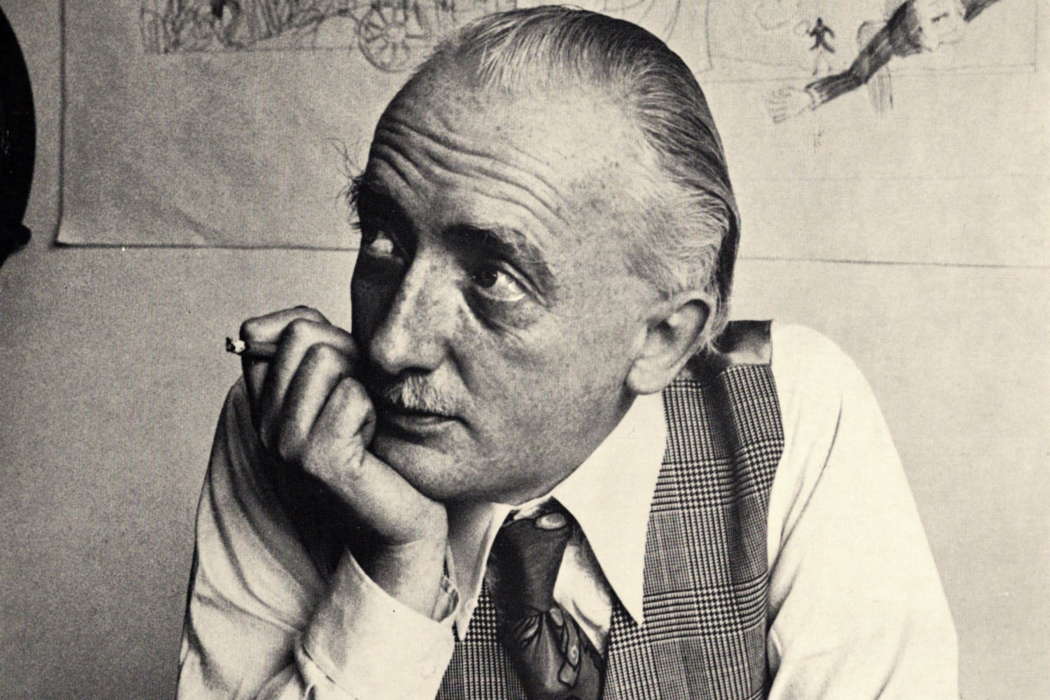

Seán Ó Riada (1931-71):

Ten Poems

The Vertical Man - Music by Seán Ó Riada. © 1969 Claddagh Records

Seán Ó Riada set poems to music throughout his all too short life. It is still hard to believe he had barely turned forty when he died especially when you see photos of him in his last years. These ten settings are not a unified work but rather a bouquet of loose leaves harvested from the short bloom of his adult creativity. Ó Riada was a Cork man and the first four of these settings are poems of Hölderlin which he was inspired to write on the passing of Aloys Fleischmann, Ó Riada's former teacher and a German musician who played a very important part in the musical life of the city on the banks of the dark Lee. As Ó Riada said himself, Fleischmann 'taught him so much more than music'. Incidentally Fleischmann's son, Aloys junior, played an even greater role in that invisible art known to some as Irish classical music.

Gebt ihr mir

Ihr Wälder meiner Jugend, wann ich

Komme, die Ruhe noch Einmal wieder?

Among these settings there are also poems by three great Irish bards of Ó Riada's generation: John Montague, Thomas Kinsella and Seamus Heaney. Heaney's Lovers on Aran is particularly well done.

Did sea define the land or land the sea?

Each drew new meaning from the waves' collision.

Sea broke on land to full identity.

When reading these lines in the present context I like to entertain the conceit that one can substitute land and sea for words and music and the crashing waves for the vibrations of the human voice. The selection ends with a forty-second, one for each year of Ó Riada's life, setting of Sekundenzeiger by Hans/Jean Arp. A somewhat surreal but tellingly cool reflection on mortality from which Ó Riada does not flinch or seek to mollify. Indeed it makes one think of W B Yeats' own epitaph.

Seán Ó Riada

The possessor of the well-trained voice on this recording is the late great Irish mezzo-soprano and contralto Bernadette Greevy.

Bernadette Greevy

She was born like yours truly in Clontarf, the same spot by the sea from where I bid my final farewell to the man who taught me so much more than music and who welcomed me into the wondrous world of poetry and song, a land where old ghosts can always meet and moth-like stars flicker for ever.

Copyright © 2 June 2024

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain