FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

More corn than gold

Some critics would seemingly like to give the impression that all classical music and all classical music recordings are wonderful. Such perennial positivity I find seriously suspicious if not downright dishonest as it stands in blatant contrast to reality. Most classical music just as with most music of any other sort or indeed most of everything in this life is just not very good.

What's great is by definition a minority that starkly stands out and is better than the majority which is mediocre or worse. If everything is great then by corollary nothing is. As proof of this I offer up this week's column. Of the dozens of pieces of music I have listened to over the last seven days with immense pleasure notwithstanding only three have stimulated me sufficiently to make me want to get my finger out and start tapping these keys.

On the positive side this state of affairs is mitigated by the sheer superabundance of music - and everything else - in this universe to such a degree that even if qualitatively only a small percentage is worth bothering with, quantitatively within that small percentage there is still so much magical music in existence that there is more than enough out there to provide you with aural ecstasy every day of your life several times a day for several human lifetimes.

1: Edvard Grieg (1843-1907):

Slåtter (1903)

Grieg: Slåtter Op 72; Norwegian Folk Dances. Vladimir Pleshakov, piano. © Orion

The bones of this piece are dance tunes for the hardanger fiddle but the way in which Edvard Grieg fleshes them out is a wonderful and enlightening example of the art of individual composition. He could have just adapted the melodies to the keyboard leaving out the notes and inflections that didn't sit well under the hands and accompanied them with four-square rhythms and tempi along with simple diatonic harmonies but that is not what Grieg chose to do. He chose to create something not exactly new but utterly unique.

Growing up surrounded by traditional Irish music and musicians I have listened to many - too many - discussions and arguments over the years about what is and what isn't valid when it comes to traditional music. I can imagine there were many purists in Norway who didn't take too kindly to what Grieg did to the original tunes he was given to work with but I feel that throughout these pieces all the changes Grieg made, and some are quite considerable, were done out of a deep sense of love and respect for this music, all the more so as it was his national heritage, and an almost giddy excitement at the seemingly limitless possibilities for arrangement and development they possess for a composer as gifted as Grieg was.

Grieg's gift for harmony was recognised throughout his career but it just got more and more unique as the years passed and so by the time he came to compose these pieces towards the end of his life his mastery was at its peak. The way he harmonised these tunes is only part, although the greatest part, of the magic here. The multiple ways in which he develops his ideas is fascinating to listen to as it unfolds in front of you.

Introducing a section where a major key melody is played in a minor key; taking notes of a melody and changing the duration of the note values to create wholly different slower sections that provide wonderful contrast and avoid what could have become monotonous in less-skilled hands; employing parts of a melody to create bass lines; playing melodies in different octaves; using the piano's pedals to somehow echo the unique sound of the hardanger fiddle's sympathetic strings.

None of these things are rocket science when it comes to composition but like many things touched by genius it seems obvious and simple after the fact. Likewise the description of how this piece was made doesn't come close to giving you any sense of the experience of listening to it as music.

2: Margaret Sutherland (1897-1984):

String Quartet No 1 (1938)

Australian composer Margaret Sutherland married or was married to - I am not sure which - an entity who was convinced that her desire to compose was a clear symptom of her mental instability; a tragically twisted example of the pot calling the kettle black and a demonstration that Philip Larkin's This be the Verse is not only appicable to parents. They should build a circular extension, with lots of mirrors, in Dante's hell just for spouses.

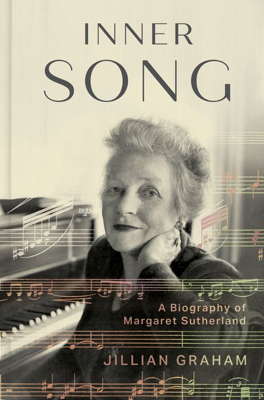

If this was the treatment she and her art received at home from the person who should have been the greatest source of loving encouragement and stalwart support one can only imagine how her musical endeavours faired in the wider contemporary community. For anyone wishing to know more about her life I can not do any better than recommend Jillian Graham's Inner Song which has just been published.

Inner Song: A Biography of Margaret Sutherland. Jillian Graham

Here I will restrict myself to my impressions of her first string quartet.

On the very rare occasions I have come across Sutherland's name it has been attached to the adjective pastoral which on the evidence of this piece is neither fair nor, more importantly, correct. There are too many wonderfully 'wrong' notes; wonderfully weird chords; unusually voiced harmonies stretched across all four instruments; too much wackiness in the scherzo; too much uncertainty and all round confounding of expectations; there is at least as much Central Europe, if not more, as there is Cotswolds in the DNA of this music; too much personality for the merely pastoral.

Take the second movement. The work as a whole has no designated key. This movement, as with the others, shows why as Sutherland accompanies her themes and melodies with chords from wholly different and unexpected keys. She creates a lot of extremely subtle but never stark harmonic tension. The pacing of this movement is delicious. She is in no hurry and allows the music to unfold blissfully and flow through varying states before a pronounced climax brings us back to that purple melody on the viola. She does all this without ever giving us too much of a good thing or ever losing sight of the bigger picture of the place of this movement in the work overall. Finally she delivers her mysterious masterstroke. Just as we are awaiting the denouement everything just stops and you are left hanging floating in mid air in an eternal moment pregnant with possibilities.

3: Nicola LeFanu (born 1947):

Moon over the Western Ridge, Mootwingee (1984)

The Raschèr Saxophone Quartet. Works of Nicola LeFanu, Miklós Maros, Maurice Karkoff, Erich Urbanner. © Col Legno

Next up we have another Australian quartet but this time one written by English composer Nicola LeFanu and one for a quartet of not strings but saxophones. This piece was inspired by a stay in the Australian outback but as LeFanu has a way with words in her genes I will let her set the scene:

great distances, great quiet; ancient trees standing in the white sand of a dry creek bed; groves of golden wattle, alive with birds; grey-green desert as far as the eye can see, broken by ranges of craggy hills; shapes ever-changing, in the shimmer of midday heat or the shadowy world of a moonlit night.

The sense of open vastness and unimaginable distance is what she most wonderfully evokes in this piece. Listening to it I am reminded of something that Tim Robinson – that great English cartographer and unique detailer and describer of the west of Ireland – said:

Somedays I feel I have truly seen things as they are when I am not there to see them.

There is an almost haunting atmosphere of stasis. To create a sense of things perceived through that 'shimmer of midday heat' there is a very deft employment of microtones to contrast with other diatonic passages for the world seen close up under that most unforgiving sunlight.

Staccato notes drip like sweat. The birds are here too in full squabbling voice. I have no idea if it is real or just a sonic mirage caused by straining my ears to hear far calls coming far in the 'shadowy world of a moonlit night' but there is a recurring melody in here in which I can't help but hear distant echoes of Ornette Coleman's Lonely Woman. LeFanu also has music in her genes but this is very much music of her own unique creation. In this recording the work is played by its dedicatees The Raschèr Quartet who in the world of saxual fourplay have a basically peerless pedigree.

Copyright © 21 May 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain