- Europe

- James Ehnes

- Kurt Atterberg

- Barry McDaniel

- Copland

- Croatian

- Big Round Records LLC

- Nottingham Trent University Choir

DEFINING OUR FIELD

JOHN DANTE PREVEDINI asks what is 'classical music' to us, why are we involved and what can we learn from our differences?

As classical music spaces finally reopen after a year of pandemic lockdown, we classical music participants are finding ourselves returning to places both frozen as we left them and yet somehow transformed in our absence. We will be making music in - and for - a world turned upside down by sickness, death and financial and sociopolitical hardship on a grand scale. What will be our place as classical performers, composers, conductors, music educators, critics, journalists, record producers and audience members in a moment such as this? In this essay, I would like to explore this question by examining the various roles we play as classical music participants and the ways in which we work together in common ventures.

What is 'classical music' to us?

I first want to affirm that by 'classical' in this context I mean Western classical, since that is how the term is typically meant when used in our circles, though the usage admittedly neglects many musical traditions from around the world also commonly called classical: for example, Turkish classical, Indian classical, etc.

A mid-eighteenth century music band in Ottoman Aleppo

The Eurocentrism of this accepted convention is worth mentioning here briefly, though the topic really deserves its own separate essay.

Detail from the 1695 portrait of English composer Henry Purcell (1659-1695) by Westphalian portrait painter John Closterman (1660-1711)

That being said, I do recognize a body of music that I believe would be reasonably uncontroversial to identify as classical because a critical mass of people - both specialists and the general public alike - knows and acknowledges it as such. Specifically, I am referring mostly to the so-called 'common practice' repertoire roughly spanning from Purcell to Debussy.

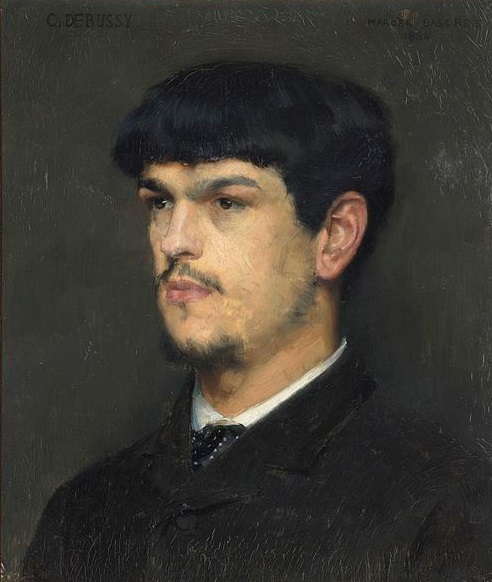

1884 portrait of French composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918) by French portrait painter Marcel Baschet (1862-1941)

I would perhaps add early Stravinsky and some other twentieth-century composers whose works have achieved widespread public familiarity (for example, Prokofiev and Copland). Less familiar to the public, though probably still uncontroversial in a classical designation, would be the earlier traditions of Western European church and court music spanning from the Middle Ages through the seventeenth century. So would be the less often performed but stylistically comparable contemporaries of the composers already mentioned.

The Kyrie from Missa Ecce ancilla Domini by Franco-Flemish composer Johannes Ockeghem (1410/25-1497) as illustrated in the fifteenth/sixteenth century Chigi Codex

Outside of these realms, the classical designation becomes potentially controversial for various reasons. One is that some music is simultaneously claimed by both classical and other genre identities. Gershwin comes to mind, as do Laurie Anderson and Frank Zappa.

American composer, pianist and painter George Gershwin (1898-1937) in circa 1935

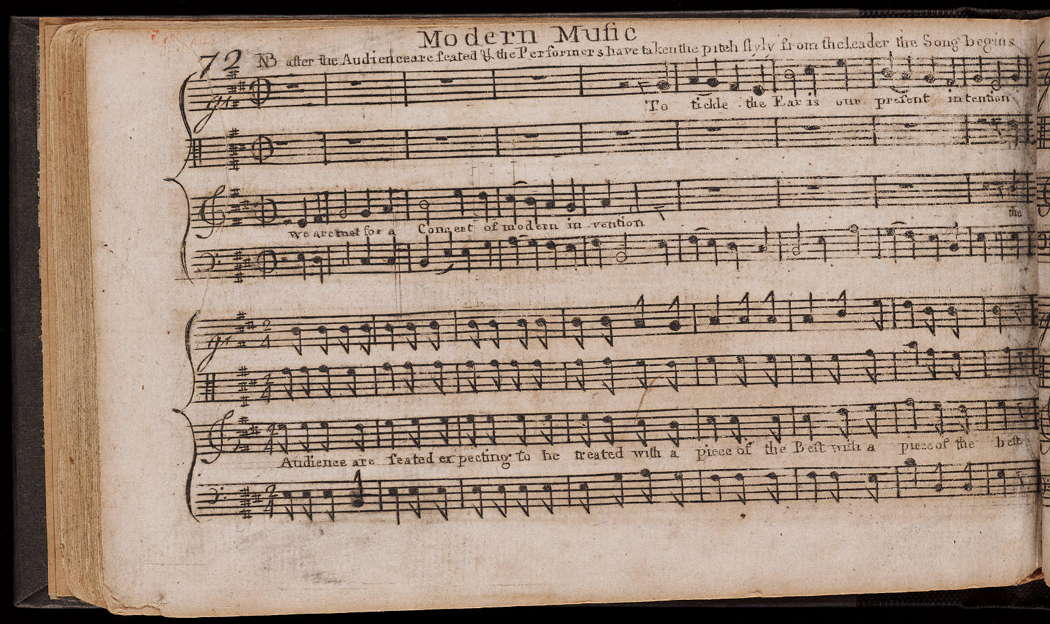

Looking further back in time, the early American composer William Billings wrote polyphonic vocal music that predates such stylistic divisions and now lives on in both the American classical repertoire and the American folk tradition of shape-note singing.

The first page of 'Modern Music' from Psalm-Singers Amusement (1781) by American composer William Billings (1746-1800)

Another reason for controversy is that some musicians wish to downplay their connection to the older traditions more universally recognized as classical, even as they reluctantly acknowledge the link. For instance, I recently read the mission statement of an orchestra in the United States that describes its genre as 'the music formerly known as classical'. Furthermore, some colleagues have asserted that 'classical music' lives on only in the academy without broader commercial potential, citing Stockhausen as an example. However, their claim overlooks the fact that many Beethoven pieces are widely used to hawk common products like laundry detergent and dog food. We must also remember that much standard symphonic and operatic repertoire was composed and originally performed under circumstances that were indeed commercial, even if the music itself is less commercialized today.

Considering the various threads that still somehow tie this music to a common lineage, I would like to propose a definition of classical music which I think, though hardly infallible or absolute, will be useful for the purposes of this essay. I offer this definition as music which either: 1) originates in the reference body of Early Modern Western European church, court or commercial music, or 2) intentionally draws upon a definitive influence of that reference body and is recognized as so doing by institutions that also curate that reference body. By defining classical music in this way, I hope to emphasize the context of different roles that people assume - such as performers, directors, teachers, etc - engaging with a piece of music under a plausible common understanding of it as they collaborate in the process.

A violin in Budapest, Hungary. Photo © 2020 Tetiana Shyshkina

Why are we involved?

Our typical relationships with classical music on the whole depend on what value we see in the field and what roles we play within it. Specifically, we may be performers, teachers, audience members or participants in some other capacity, but there are more general potential factors as well. Some of us are here to protect and preserve the traditions surrounding the existing core repertoire. Some of us are here to harness the power of the old forms in asking new questions in today's world. Some of us are here for an educational experience. Some of us are in it for business. Some of us are aficionados who simply enjoy and appreciate the craft of music and musicianship. All of these motivations are equally valid and must be seriously accounted for if we are to collaborate effectively and symbiotically as a vast and diverse network of colleagues keeping the field alive. They also define the functional meaning of this art form in our society.

An X-Award performance at Xiamen University Malaysia. Photo © 2020 Wan San Yip

What can we learn from our differences?

By examining the various reasons why people engage with the field of classical music, we can learn in more detail what the field must do for these people to keep them involved. This is important, because if we lose teachers, students, performers, audiences, composers or other constituents, the symbiotic ecosystem of our field will suffer. Such risks are already apparent in the classical music world. For example, composition students in some university programs struggle to find classmates willing to perform in their required composition recitals, because those performers receive no academic credit for playing student compositions as they do for playing assigned standard repertoire. Similarly, many classical ensembles wish to showcase a newer and more culturally diverse body of music but are compelled to cater to a paying public that often prefers what is already familiar. Then there is the perennial fear that academic experimentalist and deconstructionist traditions will pressure some composers to embrace technical innovation at the expense of socially, emotionally or morally engaging content. Some people observe these dynamics and take them as evidence that our field is out of touch and cannot address the needs and perspectives of the contemporary world. I believe we can meet the challenge, but all parties have serious work to do to make that happen. We need not abandon the roots of our tradition, and we can instead consider their power as a phenomenological and technical toolbox that can be used to articulate and present music that captivates future generations.

Dutch National Opera and Ballet in Amsterdam. Photo © 2019 Keith Bramich

As the lights come back on and we reenter our concert halls, opera houses, recording studios and universities, take a moment to reflect on the ways in which we all depend on one another as classical music participants in an evolving musical tradition. It may seem a daunting and nebulous task, but in a world undergoing such seismic shifts, we need to remain alert to our obligations to engage in the broad culture of this music. Nor can we afford to fall prey to primarily consumerist motives, though basic financial support is always important. Our shared classical music culture has long been defined by practice rather than sheer consumerism, and that practice has resulted in the reaffirmation of distinctive qualities that make our field so attractive to its devotees. The culture of classical music - like a spoken language - may not be a product that sells widely, but it is a valuable asset in community building that needs to be kept and maintained through interdisciplinary practice. Lastly, this diverse community in turn needs nurturing on all fronts. Otherwise, the networks that sustain us risk disintegration.

Connecticut, USA