DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

Bringing Out the Paradoxes

JEFFREY NEIL delves into the nuances of Mozart's 'The Magic Flute' in San Francisco Opera's current production

I doubt I am alone in failing to grasp the nuances of plot in The Magic Flute no matter how many times I see it - in spite of a lifetime studying precisely that genre of romance with its complicated plot twists and - if we're being honest - random episodes. Mozart's final opera was a collaboration with librettist and comedic actor/singer Emanuel Schikaneder to create a humorous fairy tale that also advanced Enlightenment ideas and possessed coded references to freemason rituals. But the fairy tale is in its heart of hearts a benighted form of storytelling, dependent on repetitions that don't necessarily lead to self-knowledge and curses that a character can't reason himself out of. There are episodes that are merely there to entrance, but have no purpose in advancing a plot along Aristotelian lines where some action inevitably leads to another.

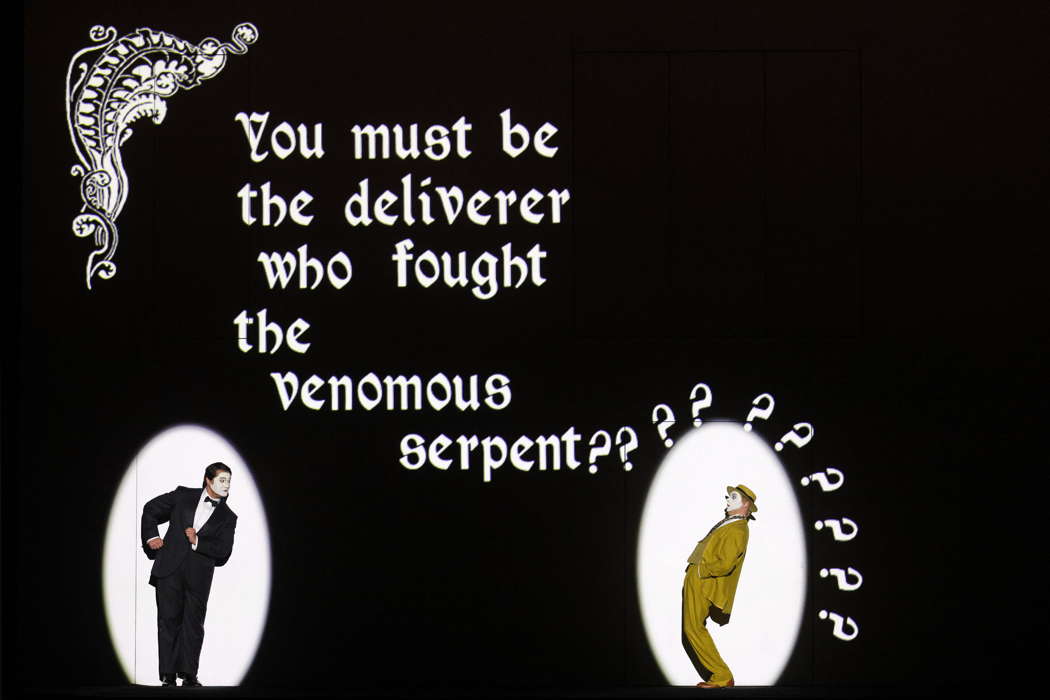

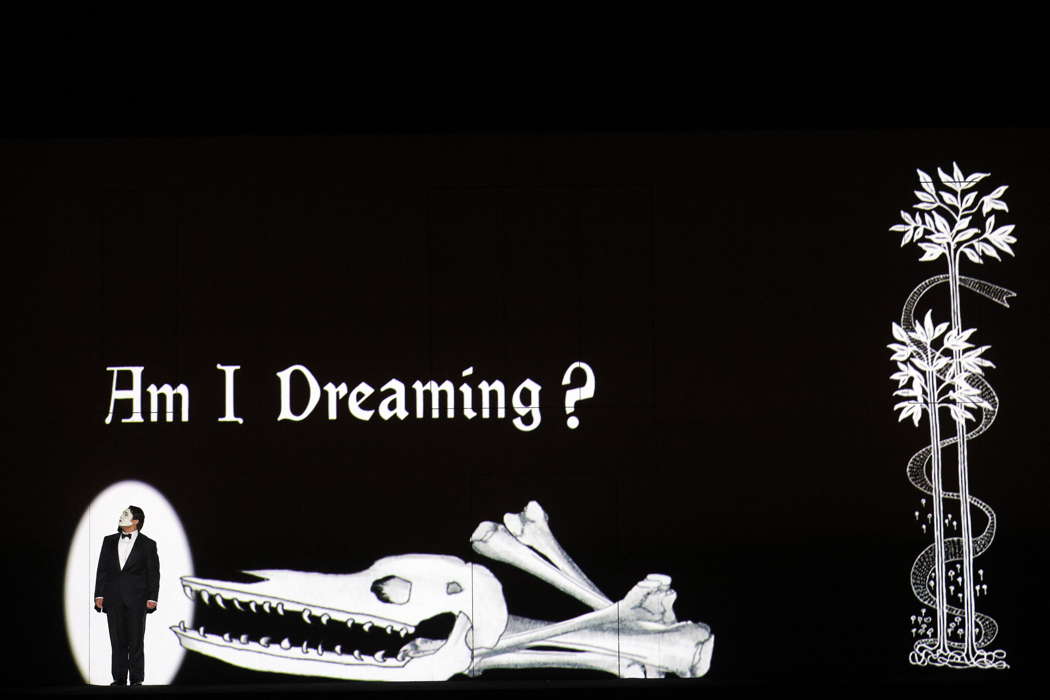

Barrie Kosky and Suzanne Andrade removed the Singspiel altogether and replaced spoken dialogue with silent cinema intertitles accompanied by forte piano renditions of Mozart's Fantasias.

Suzanne Andrade (left) and Barrie Kosky. Kosky photo © Jan Windszus

In doing so, the animated vision enriches the underlying paradoxes of the opera, such as the elevation of 'reason' and the ideal of a sublimated, 'wiser' love. The Komische Oper of Berlin's production awakens us to the absurdity and dysphoria under the quest for transcendence, but not by bludgeoning us with depressing scenery and a cast arrayed in black trench coats. Instead, delightful animations and creative blocking make us laugh our way into the realization.

Amitai Pati as Tamino (left) and Lauri Vasar as Papageno in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Even without taking into consideration the Masonic codes embedded in the music and the narrative of The Magic Flute, there is much that is perplexing. For starters, the score is sometimes at odds with the musicality of the poetic language itself. Mozart wrote music in parts that obfuscates the regular meter or rhyme of the poetry. Then, there is the plot, which is confounding if one gives it any thought at all. The Queen of the Night and her three maidens save Tamino from the serpent; the purportedly evil queen provides him and Papageno with the help from the three boys and the enchanted tools to confront any conflicts; and let us not forget that the Queen is the one who has introduced the lovers to each other without forcing them to undergo any trials. Sarastro, on the other hand, abducts the princess and then forces her and Tamino to undergo totally unnecessary trials. But in the rhetoric of the opera, Sarastro is elevated and considered an enlightened ruler. The logic of the plot is maddening.

Kwangchul Youn as Sarastro and Zhengyi Bai as Monostatos in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

This problem is intrinsic to the genre itself. The idea of a fairy tale serving the purpose of pushing forth enlightenment values is paradoxical. The world of the fairy tale exists under irrational curses, which reflect the reality of the human psyche. This is the realm of the archetypal, the associative rather than the logical, and the resonant paradox, which holds two contradictory ideas as true: love is pain; hatred is love; madness is sanity; folly is wisdom, and so on. But fairy tale is also the genre of polarized characters - good and evil, ugly and beautiful, old and young. The Magic Flute pushes toward a choral triumph in which good wins over evil, light casts out darkness. The Queen and her entourage simply descend into hell, and 'The good are triumphant and justice is done. Through knowledge and courage all glory is won!' Unlike in the average fairy tale, it is not at all clear who is good, nor why Sarastro is the arbiter of wisdom and knowledge, other than that he styles himself as such.

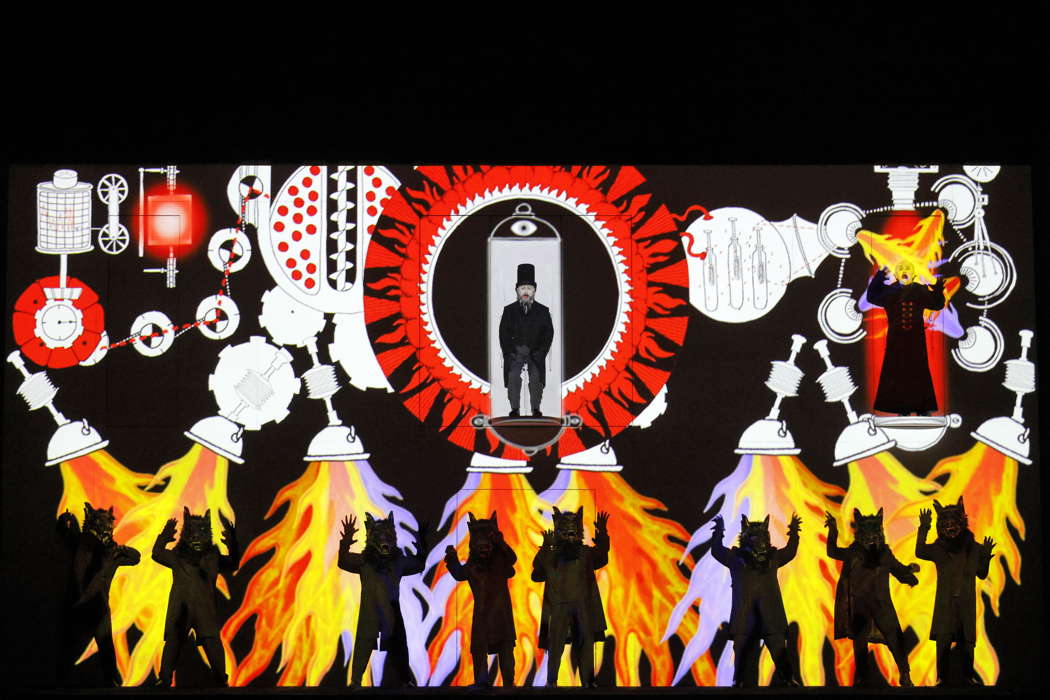

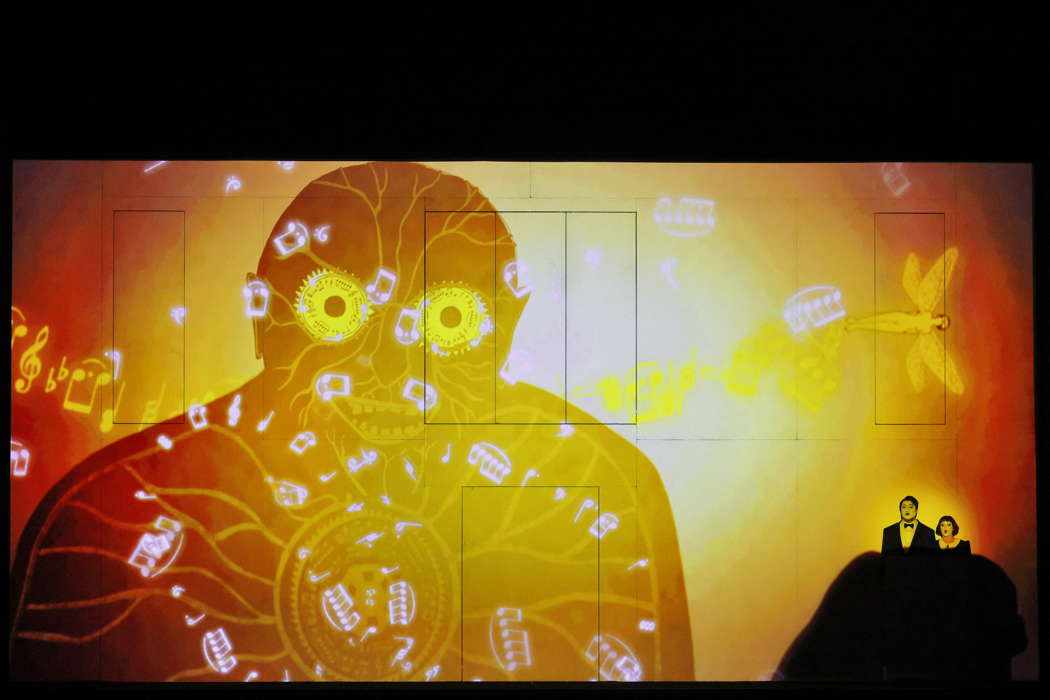

The Berlin Komische Oper production, internationally celebrated since its premiere in 2012, brings to the forefront the paradoxes of the opera. Harkening to 1927, the year that talkies hit the big screen, this production demonstrates how well silent film engages audiences with stimulating and meaningful animation that functions as backdrop and also interacts with characters. The costumes and make-up also reference specific silent film stars, such as Louise Brooks and Max Schreck. But this is not a quixotic gesture to the culture of the Weimar Republic or to the silent films of that era, nor is it a gratuitous use of technology as gimmick. Like the 'paratext' of illustrations that surrounded medieval manuscripts or the books which Mozart read, these animations are in a powerful dialogue with the music and the narrative. They feel necessary, as I'll show in my examples below, problematizing the terms that this opera upholds. The ironic animations illustrate how truth, wisdom, and knowledge are tied to a masculine identity that both chases women and simultaneously seeks to cast them out from the sacred realms where knowledge is produced. Although we lose some nuance of plot and characterization by replacing spoken dialogue with a few spare intertitles, the production demonstrates the immense power of the age-old art of pantomime and non-linguistic forms of representation.

From left to right: Olivia Smith as the First Lady, Ashley Dixon as the Second Lady, and Maire Therese Carmack as the Third Lady in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

In the opening scene, for example, the three ladies are smoking with blasé expressions. It is only the possibility of sexual intrigue with catch-of-the-day Tamino that excites them. Desire pulls them out of their apathy as they sing about their wish to be the one left to watch over him. Desire, the engine of the romance genre to which fairy tales also belong, is the sputtering, smoking engine of narrative. Paul Barritt's animation already begins to position the story not as leading to a sublime love, but a distraction from a fearful reality: in the opening scene, Tamino is actually already in the animated digestive tract of the serpent when he is saved. Hearts descend upon Tamino from the three ladies as a kind of parody of love, especially when being 'saved' from the serpent looks very much like a charade.

There are images of grotesque desire throughout: When Papageno dreams of female companionship, the animation illustrates turkeys and chickens going through a conveyor belt and turning them into cooked food on a platter. Desire is always consumable, commodified, and very often, grotesque. When not that extreme, we see vaudeville dancers' legs on birds, sometimes flashing side to side, as if they were on a neon sign. The animators seek to continually bring the story back to the gritty and not allow for that transcendence that Sarastro aims to manufacture through his trials.

There has been a great deal of mystery surrounding the Masonic codes in the opera, as if the repetition of threes - three ladies, three boys, three trials - was particular just to the Masons. Most of this is balderdash to the audience. Anna Russell summed this up perfectly in her comedic lecture on Flute:

The trials of Tamino and Pamina are copies of ceremonials used in masonry, and it all has very deep meaning except the rest of us haven't a clue what it is. In fact, what they were doing was a subliminal sale for freemasonry. The pope was furious. He forbade Catholics to go and see it, but since it was so subliminal and on the face of it was a faerie story, he had a frightful time putting his finger on exactly what was wrong with it.

Listen — an excerpt from Anna Russell's lecture on The Magic Flute :

The focus on the freemasons' enigmas obscures some of the sources of Die Zauberflöte, however indirectly they get there. Apuleius' Golden Ass, a second century Latin story, was the equivalent of a bestseller in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and permeated subsequent fantasy stories all over Europe. There we see the archetype of seductive women as enchantresses who bite off men's faces when they sleep, turn them into donkeys for the fun of it, and have sex with beasts in front of thousands of onlookers as a manifestation of a bottomless well of sexual deviance. The German Zauberin is not just a female magician, but a sorceress, and the magic of Zauberflöte is precisely that of the sorceress, the Queen of the Night, whose main flaw is the combination of magical power and the fact that she is a woman. In the story of Cupid and Psyche, which is embedded in The Golden Ass, vengeful and overbearing Venus must be brought to her senses by the wise and rational Jupiter. At the end of Apuleius' meandering tale, the donkey Lucius becomes a man again only by joining an oriental cult of chastity, much as Isis and Osiris function to bestow the legitimacy of chaste love on the union of Tamino and Pamina. You can't understand the madness of Flute's plot without these embedded references to Apuleius, not the freemasons.

Amitai Pati as Tamino and Christina Gansch as Pamina in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

Ortega y Gassett wrote about the end of transcendence or romanticism in The Dehumanization of Art. Modern art, he explained, would be one in which:

Metaphor ... has the possibility of eluding reality, creating new realities, and is linked to the taboo, that which cannot be spoken about because society depends too much upon it.

That seminal work on modern art was published in 1925, two years before the setting of this production. There is much that is taboo here in how the metaphors bring us back to a deflated romance repeatedly, rather than catapulting us into the sublime. When the three ladies try to woo Tamino into serving the Queen and rescuing her daughter, they don't show him an oil painting of Pamina: the animation shows her portrait as an abstract composed of cigarette plumes, all of it the color of a burning pyre. Desire is sultry and decadent, part of a fallen world not a vehicle to a higher realm.

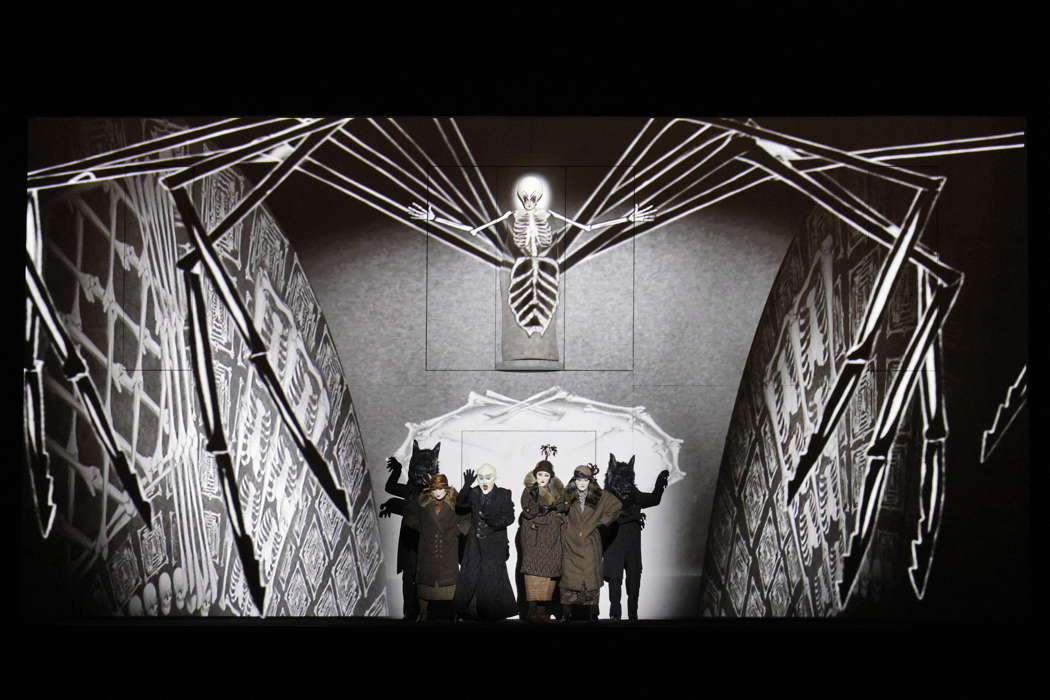

The production makes no bones about representing the Queen of the Night in various repulsive variations: without animation projected onto her, she is a white statue, folds of fabric and a comedic mask that at times look like hospital bandages. The projected animations transform her into a skeleton and also a spider.

Olivia Smith as the First Lady, Zhengyi Bai as Monostatos, Anna Simińska as the Queen of the Night (above), Ashley Dixon as the Second Lady, and Maire Therese Carmack as the Third Lady in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

In doing so, she represents all of the forms of moribund desire that operatic women take on and from which Tamino must be saved - sexual obsession and death by venereal disease, entrapment in a web of deception, and a void. Behind the transcendence that Sarastro offers, the woman is a kind of colorless vacancy, a dead statue upon which masculine desire is projected.

Sarastro and the off-stage 'Speaker' are various incarnations of a masculine identity, much as the Queen is represented in manifold ways. The Speaker 'awakens' Tamino to a version of reality in which the Queen has lied to him, Sarastro is not evil, and the temple is a place of peace. The Speaker has an embedded camera projector and Klugheit, or wisdom, written out for us to read. Indeed, Wahrheit, or truth, also appears as part of the enlightenment machinery of spinning cogs and pendulums of clocks and watches that symbolize a masculine knowledge. The animation makes clear that even these lofty ideas are constructions, like the mechanical creations, and they produce their own reality. No idea is elevated - all are toyed with - and even the notion of 'enlightenment' is satirized by the drones that light up characters as they walk along. These gadgets represent male paranoia rather than pointing to a better society ruled by enlightened men.

While transcendence is not the goal of this production, there are many moments of amazement nevertheless, which are in keeping with the spirit of The Magic Flute. There are 729 animation cues in which the actors must be in sync with the animation.

Amitai Pati as Tamino in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

One of the most spellbinding feats was when Papageno stroked an animated cat that follows him around. The moment captures the magic of the ancient form of pantomime and of puppetry, which has so often featured in productions of The Magic Flute.

Director Eun Sun Kim's orchestration, sadly, drowned out the voices of a number of singers at different points. Anna Simińska, as the Queen of the Night, displayed control in the melismatic coloratura of 'Der Hölle Rache'. Her voice has a clarion sound, but the orchestra generally overwhelmed her. Performances were uneven with some strong moments. Christina Gansch, as Pamina, shone in her lamentation aria, 'Ach, ich fühl's' from Act II.

Lauri Vasar, as Papageno, had a voice that did not tire, and he could fill the hall in a way no other singer could. His comedic acting and deft maneuvering of the blocking constraints were also considerable accomplishments.

Lauri Vasar as Papageno in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

The ensemble and choral pieces eclipsed most of the arias, and the finales to the first and second acts were particularly well sung. When he is accompanied by other singers, Kwangchul Youn was at his best as Sarastro with a velvety bass voice.

Kwangchul Youn as Sarastro in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

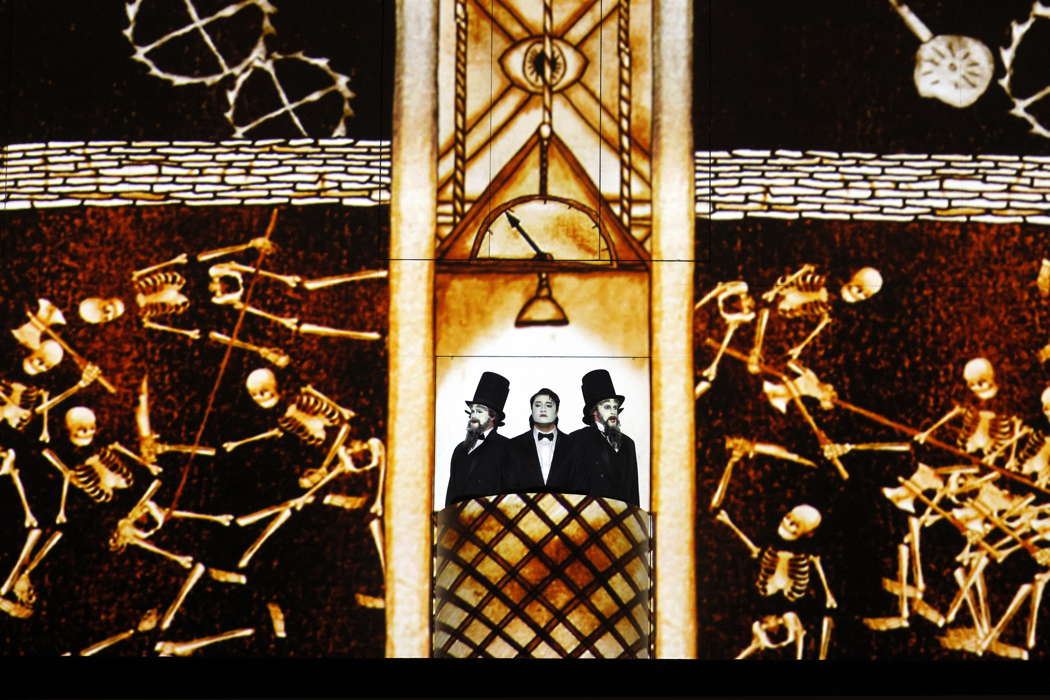

The closure of the final act shows male paragons of Enlightenment values, headed by Sarastro, descending past strata of skeletons - even as they sing of ascent. It's a wonderfully satirical commentary on the whole theme of transcendence in the opera.

Amitai Pati as Tamino (centre) with Thomas Kinch and James McCarthy (the Armored Men) in San Francisco Opera's production of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Photo © 2024 Cory Weaver

The banishment into hell of the Queen of the Night and her entourage is accompanied by a film reel quickly spinning to its end - as if all the illusions and representations of the film are finally petering out. The final tableau is of the chorus separated by gender, women on one side in austere, ugly black frocks and the men in Victorian top hats - a throwback to a past era in the context of the Weimar setting. The music is triumphant, but this is an image of a severe schism of the sexes, a retrograde vision of sexuality in an opera where desire is never transcended but merely segregated, sorted out, or banished. This production brings out the paradoxes of the opera, entertains, and delivers a dreary message that one cannot help but enjoy.

Copyright © 13 June 2024

Jeffrey Neil,

California, USA