FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

An Evening of Vocal Distinction

RODERIC DUNNETT reports on Massenet's 'Cendrillon' from the UK's Royal Birmingham Conservatoire

The Royal Birmingham Conservatoire (RBC) has raised itself, not least under Julian Lloyd Webber's leadership, to new heights; certainly on a par with London's four principal colleges, and not least, the Royal Northern College in Manchester - places one might liken to New York's Juilliard or Philadelphia's Curtis Institute.

Indeed RBC, with Stephen Maddock at the helm, is now, in an increasing number of faculties, the college of first choice for many aspiring young musicians. Hence the first thing to say about its latest bright, witty, resourceful opera production - Jules Massenet's Cendrillon - is that the Conservatoire, its finest achievements meriting high-level support from the discerning Royal Opera-connected Linbury Trust, is realising its true potential by progressing from mere 'opera scenes' to performing entire operas. Recent ones have proved themselves excellent; and so has this boisterous Cendrillon.

Staged at the newly developed Gas Street Central venue, their treatment of Massenet's version of the Cinderella fairy tale had singing full of zest, flair, precision; a top-class, beautifully honed chamber orchestral ensemble; and some splendidly rehearsed, clever individual performances that were as polished as they were captivating.

The choice of repertoire itself explains, to a degree, this palpable success. Vocal and Operatic Faculty head Paul Wingfield settled on an opera far less performed than Rossini's La Cenerentola. To explore the French composer's distinctive, undervalued output - Thaïs, Le Cid, Don Quixote are occasionally revived, but more the most celebrated pair of all: Werther and Manon - was a bold decision. Further credit, it offered plenty of scope for this talented young troupe.

For a nationally celebrated music and drama conservatoire (equivalent to, say, London's Guildhall), the quality of the singing is surely what mattered here most; abetted, true, by some deliberately ham acting inculcated by Director Matthew Eberhardt, all of it fun - albeit marginally limited due to a neat but constricted raised stage (and additional sidewalk) on which the artful events of the main action took place. But there was a benefit: some scenes, especially the most ludicrous, were unusually immediate and laughingly in-your-face. You couldn't miss the jokes and the pastiche.

Making a mark in a short role, Sydney Sheffield brings very desirable news in Massenet's Cendrillon in Birmingham. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

The best of the vocals - and those included a very forward, forceful chorus - revealed much: the company's high class tutoring, discipline, finesse; and the inspiring quality imbued in its protégés by RBC's Vocal and Operatic Department. The casting showed intelligent and welcome good judgement. Amid the comedy and giggles, there was some serious talent on show. There were at least three superstars, and other near-superstars. The result? An evening of vocal distinction. At almost every point its young performers lived up to the Conservatoire's, and the audience's, hopes and expectations.

The vocally excellent RBC Chorus is presided over by a very prominent Doyen (Dean) of the Faculty - Joe Yates. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Cendrillon was launched ably, and also poignantly, filling in the story so far, by Cinderella's hapless, hen-pecked daddy (Pandolfo): a fine, pleasing baritone, attractive delivery and promising intonation from Matthew Pandya, invariably able to reach down to lower registers, smartly neat in skippy syncopation, and particularly moving in the scene where he and Cendrillon long to escape their idiotic household and set up home in the forest - 'Let us leave the town, you have forgotten your childish joy'. Joylessness is indeed what permeates and plagues their current lives. Pandya doubled with Oliver Barker: Birmingham fielded two alternate casts, giving not just seventeen but double that number of opportunities - plus some twenty-four twin cast chorus members.

Attractive baritone Matthew Pandya as Cendrillon's father Pandolfo, in an unusually dramatic moment of Massenet's Cendrillon in Birmingham.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

How Pandolfo and daughter ended up with the dire Madame de Haitière - nicely described elsewhere as a 'termagant': more than a mere shrew, here a real bitch - one wonders; but the result is that Cinders acquires an odious, bullying stepmother. Bizet was Massenet's great friend, Saint-Saëns a contemporary - they came in a kind of interstices between César Franck and the Impressionist generation befriended by Chausson, his pupil. How Bizet, if he had lived beyond his thirties, and Massenet might have shared dramatic and musical qualities is a matter of speculation, but Massenet certainly knew Carmen.

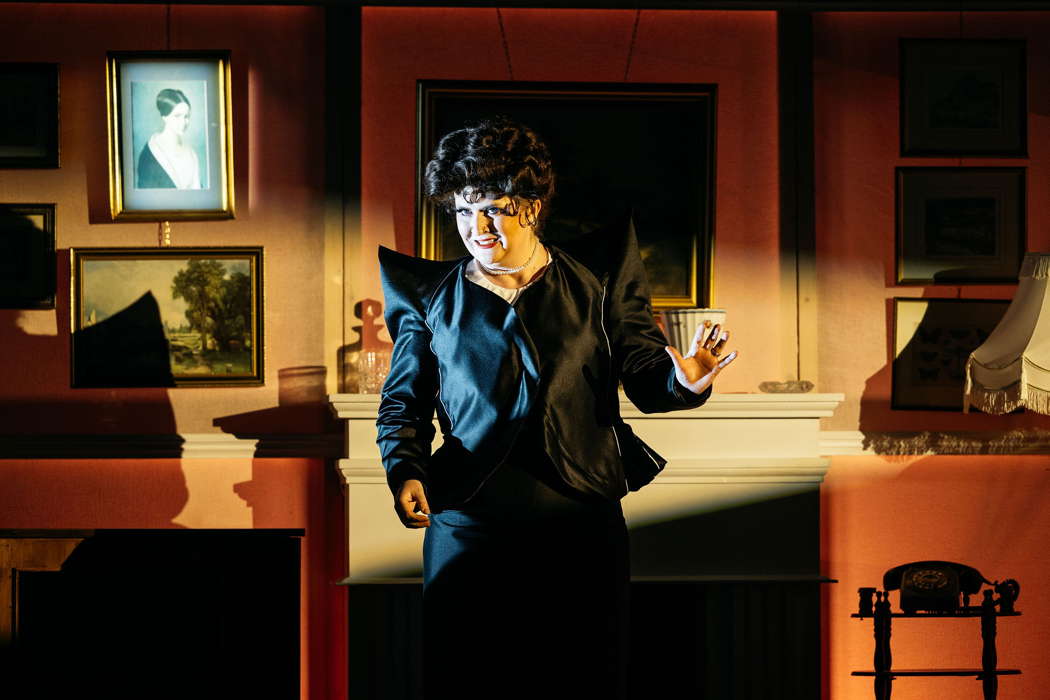

The mother, Hannah Morley, invited boos every time she stepped onstage. Her aspirations to rise above her station are ridiculous, although she is already well-heeled, a class or two above her ill-fated husband and overdressed: one of many spoofs by the costume designers of RBC's collaborators, The London College of Fashion, who came up trumps every time.

Morley's performance was all the more in-yer-face, a vile cow whose screwed-up visage, really grotesque - not just ambitious - was as terrific as it was pastiche, thanks to her proximity onstage. Each time she opened her mouth, social climbing, abetted by her miserable offspring, or bullying anyone in sight, one marvelled at not just the richness of her tone, but the maturity. She produced a wonderful, arresting, stylish mezzo-soprano: in low range, which Massenet demands, to dizzying impact, almost a wonderful contralto, of stirring richness. Such an unerring treat, one almost forgave her dreadfulness.

Or perhaps not. Her two dire, conniving, catty daughters, Noémie (Polly Clarke) and Dorothée (Hannah Devereux) were as ghastly as her. When these two revolting hypocritical charmers sang (brilliantly) in duet, they recalled, almost to the letter, the card-playing Frasquita and Mercédès from Carmen. So though one loathed them - and how well these two acted the awfulness - one could not but be entranced by their stylish duetting.

Dressed supposedly to kill: Cendrillon's

smug, bilious, couldn't-care-less stepsisters

show off to their oppressed younger sibling,

in Massenet's Cendrillon in Birmingham.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

And one trio with obnoxious, manoeuvring Mum was stupendous. The student costume designers brilliantly dressed the ugly - and ironically very pretty - semi-sisters too. When the awesome threesome reappear quite soon, it's all polka dots: black on white, white on black - hilarious contrast - but mum in an ominous all-black which summed her up dark, brutal, bossy personality aptly.

The RBC's Hannah Morley, terrific as Cinders' dire and revolting stepmother, and a mezzo of real stage presence. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Everybody, again, chorus included, had - impressively - superb enunciation: much owed, doubtless, to Language Coach Mỹ Linh Ton (originally from France, Toulouse). It showed uniformly: their French enunciation was perfect. It made all the difference. Here were results she, and they, could be proud of.

It would be good to laud the alternate 'blue' cast as well (as Madame, India Harding), and it can surely be taken that many shone in broadly the same way as our 'green' cast whom I was lucky enough to catch. But the acoustic shone as well: compacted by a low ceiling, a kind of empowering echo chamber, the instrumental detail came over splendidly. And where the orchestra doubles one or other voice, it was so well contained, so carefully marshalled, that it never overpowered.

After such grotesque parody, where does hope begin? With the aririval of La Fée - the godmother of the story. Her appearance as a silhouette at the back was incredibly vivid - one of three or four oustanding lighting effects from LAMDA-trained Luca Panetta.

The shadow of her Fairy Godmother - the brilliant Ana Salaridze - on her way to use magic to help poor Cinderella. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Another was where he enfolds the two lovers in deeply involving, arresting near-darkness.

A rare marvel of lighting and poignant,

evocative moment as the two lovers

are magically brought together.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Chloe Matthew's enticing sets, the domestic parodied, the palace touching, centred upon two picture-festooned walls: the sitting room of the ill-fitting family; and, more specially, the picture-adorned hangings of the soon-to-be-revealed Palace. The latter, in particular, was pure enchantment, especially as a tall backdrop to the grieving monarch.

The Fairy was abetted by her coquettish and supportive six-girl team of Spirits, who shared her charming stylishly layered pink dress, dreamed up by as many as thirty or more joyous, go-ahead young members of the College of Fashion.

The Fairy Spirit's five loyal attendants examine the special shoe given to Cinderella by the Fairy. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Actually two distinct teams, for them too, hence contrasts, either collaborating or (quite likely) independent of one another, with Ana Salaridze (double: Hailey West) as the intriguingly-hatted La Fée. More significantly, fantastic in uppermost register, she would grace any professional stage.

She delivered, fabulous casting, the most amazing coloratura: far from a shrill Queen of the Night - as whom she would also excel - but enchantingly pure and light in highest tessitura, not unlike the soaring, moving role Massenet had allotted to the sensational lead in Manon fifteen years earlier. The little-known parallel I would draw attention to is the besotting, high-soaring Nightingale in Walter Braunfels' neo-Romantic opera The Birds. Nobody knows it. But from Salaridze a tip-top voice and sensational control. A delight at every point. One kept aching for her to reappear, and when she did - wow!

Ana Salaridze as the miraculous Fairy,

saviour of Cinderella - a soaring voice

of astounding, magical precision.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

But in Cinderella - the version (1810) by Nicolas Isouard, likewise in French; by Rossini (popular and triumphant); or Maxwell Davies (for children), the central figures are Cinderella and her longing Prince Charmant. Cinderella's enchanting, shy, hectored personality here won our hearts from the outset. Mezzo-soprano Samantha Lewis, clad in a simple, one might almost say dust-coloured long grey dress, so put-upon that cleaning and tidying the house, or pretending to sleep, are her only escape, captured - her opposite number was Noémie Johns - the innocence and plaintiveness of her increasingly assured, daring character.

Samantha Lewis, a touching, desperately distraught Cinderella in RBC's vivid staging of Massenet's Cendrillon. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Cinders comes up with the most spectacular singing, at best in higher register - a practice, as it were, for her encounters with the Prince, where Massenet unfolds melodic material that sends her, once more, into the stratosphere. It was in those aery heights that Samantha shone most: truly astounding moments where her voice unveiled its really distinctive quality. Wan in demeanour, but certainly not in voice.

At her miserable home, the appallingly maltreated Cendrillon (Samantha Lewis) appeals for some alleviation of her cruel, abandoned situation.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Innocent Cinders may flee the court in a whiff of smoke, but is not cowering: she has the courage and determination to be a suitable inamorata for a Prince who is seeking precisely the qualities in a life partner that she displays.

Hope at last - Cinderella and the Prince in a joyous moment as love and infatuation seizes them both. Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Both the folk-tale story - Henri Caen, 1857-1937, collaborated on five libretti for Massenet - and the music embrace several enchanting, lulling dream-like sequences. Dreams, or moments to reflect, are what Cendrillon espouses to escape, and they yield some of the most evocative and poetic touches from the libretto, which likewise indulges in touching symbolism: moon, setting sun, seashore, orchard, oak tree, forest, crickets, glow-worms(!) To evoke it, a miraculous solo violin (Ming Zeng), viola too (Jinhe Huang), violins one and two (Tiantong Wu) magical in duet, and at times the whole string quintet. It offered not just an exhilarating cello soloist (Tiange Li) but a remarkably restrained, sensitive double bass (Anish Velankanni), who watched like a hawk, and whose contributions - and Massenet supplies some significant melodic material to ensure it - literally sang.

Anish Velankanni, double bass. One of the many supertalented members of the polished orchestra in the RBC's memorable production of Cendrillon.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

But there were many appealing moments, or whole sequences, from Wingfield's masterfully managed, incredibly refined players: dancing paired clarinets and flutes; the horns; a single trombone (hence important in support); his able, deft percussion section (with one rare marvel: a xylophone upholding the entire chorus). At several moments Wingfield drew gloriously engineered diminuendi from them all; one notably in which cello, then flute, emerged pristine.

Paul Wingfield, the moving force behind

this production, and head of the RBC's

Vocal and Operatic Studies, evoking some

marvellous playing from his beautifully

rehearsed, highly proficient orchestra.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

More than one uplifting and illumining oboe solo (Will Sherratt), for instance enhancing a beautifully treated exchange between father and daughter, which the composer offsets with passages for cor anglais (Samantha Croke). Another where his two horns (Alexandra Argirova and Licheng Hua) surfaced like Wagner tubas - it's worth remembering that Wagner was an unavoidable influence on mid- (and late-) nineteenth century composers, certainly on Massenet, who was championed by Berlioz, encouraged by Liszt, and a Prix de Rome winner: the Paris Conservatoire's highest award.

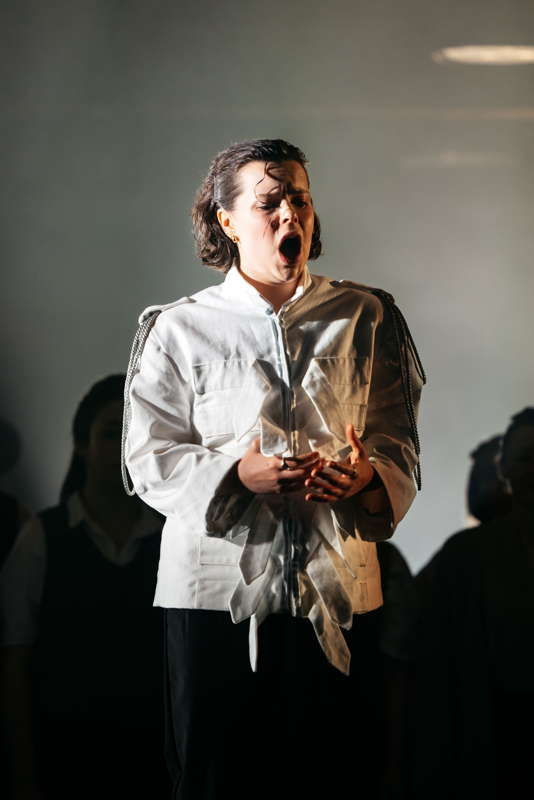

But what of Cendrillon's fabulous Prince Charming? His beautifully designed attire means nothing to him: 'Spring without roses'. Every time mezzo Charly Browne opened her mouth, it was pure Nirvana. He/she, even more than Cinders, emerged as the most poignant, desolate figure. Noone in his attentive court could cheer him. Along comes sudden optimism, then despair, instantly upon meeting and, more importantly, losing his Cendrillon.

The immensely charming and moving

Charly Browne, exemplifying the

nobility but emotional isolation

as the yearning Prince Charmant.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

Browne created an enchanting, profoundly moving character: his stance, his frozen, grieving demeanour, but above all his unremittingly gorgeous voice conveyed the affliction of isolated royalty, who has garnered a lowly - and empathetic - potential partner, yet faces deprivation again. Hope withers; all his finery, splendour, servants, portraits, tapestries mean nothing. His life is doomed to be solitary, arid, dejected, unfulfilled, abandoned and heartbroken.

Mezzo-soprano Charly Browne, superb as the distraught Prince Charming.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

But to explain the Prince's inspiring ability to draw our sympathy and capture our hearts, it was Charly Browne's singing, intimacy, pain, which utterly enchanted. A lovely, I would almost say unique, timbre to her mezzo-soprano, gorgeous across the entire range: the richest of sounds, the most sophisticated delivery for a young performer, a purity which surged through every note she sang. Here was a singer of the very top quality, who should be snapped up by every opera and summer opera company that has the insight to engage her.

The lush finery of his tapestried palace

brings scant joy or happiness

to Charly Browne's lovelorn Prince.

Photo © 2024 Greg Milner

The two lovers, in character, are perfectly balanced, by contrast: neither expects genuine affection; both feel it is against all odds that they will discover it. Running throughout everything is Massenet's extraordinary stylistic variety, his sheer versatility - a hybrid quality that has drawn many modern criticisms, yet seemed here ('his lyrical invention, dramatic skill, fluency and charm') akin to Offenbach, or much of earlier French nineteenth century (even skilfully poached from the seventeenth or eighteenth). The Wagner influence mentioned above is subsumed and freshly explored, not merely copied. He seems to preempt Puccini time and again, and the dream sequences almost anticipate Dvořák's Rusalka (1904), just five year later.

It would be idle to argue that this Cendrillon ticked all the boxes. There were aspects and touches which were very good, even if not always soaring. But there was enough here to deserve lively applause and a very high rating indeed. At countless points, we were treated to a wealth of talent, in a thoroughly joyous - and touching - production. One can scarcely ask more.

Copyright © 5 April 2024

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK