SPONSORED: Ensemble. Unjustly Neglected - In this specially extended feature, Armstrong Gibbs' re-discovered 'Passion according to St Luke' impresses Roderic Dunnett.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Unjustly Neglected - In this specially extended feature, Armstrong Gibbs' re-discovered 'Passion according to St Luke' impresses Roderic Dunnett.

All sponsored features >>

Dramatic, Frightening and Profound

KEITH BRAMICH experiences multimedia compositions by Yannis Kyriakides

Born in Cyprus in 1969, composer Yannis Kyriakides moved to the UK in 1975, where he studied musicology at York University, and has been living in the Netherlands since 1992. His teachers included Louis Andriessen and Dick Raaijmakers, and he undertook research at Leiden University on concepts of multimedia composition. He has created about two hundred works, won many prizes for his compositions and he teaches composition and multimedia at the Royal Conservatoire in Den Haag.

Yannis Kyriakides speaking after the interval of the 26 November 2023 concert in Amsterdam's Orgelpark. Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

While visiting friends in Amsterdam last weekend, I experienced a full length Sunday afternoon concert of Kyriakides' creations, held on 26 November 2023. Het Orgelpark, the concert venue, describes itself as 'the international concert stage in Amsterdam for organists, composers and other artists' and is a converted church next to Amsterdam's Vondelpark.

Exterior of Orgelpark in Amsterdam. Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

In 1994 the Parkkerk was repurposed, initially housing dance classes and an IT company, and then taken over by the Utopa Foundation in 2003 and converted into the current Orgelpark. Activities include commissioning of music, concerts, study facilities, masterclasses and symposia. As well as restoring the building's Sauer organ, seven other organs, of various kinds, have been installed in the concert hall, making it a very unique space.

A view of the colourful interior of Amsterdam's Orgelpark, during the interval of the 26 November 2023 concert. Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

The first half of the concert, consisting of two first performances, was a showcase of the less conventional multimedia aspects of Kyriakides' work, beginning with Gaze Units for soprano, organ and video projection. The organ contribution was invisible as far as the audience was concerned, with our full attention guided to soprano Michaela Riener. She stood on stage, behind a translucent gauze, so that we could see her singing. A video camera pointing at her face sent her image to facial recognition software which was used to project a computerised face mask, overlayed with the points and dots from which it was constructed, onto the gauze in front of the singer. This grey, seemingly lifeless mask, with two eyes, a nose and a mouth, but otherwise devoid of human features, blinked, sang and turned its head in different directions, copying the singer.

Michaela Riener performing Kyriakides' Gaze Units at Amsterdam's Orgelpark. Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

Riener sang, very expressively, a series of words and phrases describing facial expressions and commands. Examples were 'look up and around', 'glance', 'squint', 'blink', 'slitted eyes' and 'wide-eyed'. We could see her singing and looking in different directions, but the computerised face, in front of her, was many times bigger than hers, and there was a bizarre disconnect between the two.

Aspects of Rieber's facial expressions were analyzed by a Viola-Jones-type algorithm and also possibly generated an organ score, which began with long held notes. Sometimes there were tremolo effects and repeated patterns. As Riener's phrases became more dramatic - 'twitch', 'rapid' and 'morbid contraction', for example - so the organ contribution also increased in energy with, at one point, short stabs of very high notes. Combined, the effect on me was dramatic, frightening and profound, and when the work ended with 'eyes closed shut' from Riener, who then put her hand over the camera to make the projected face mask disappear, it seemed to me that Kyriakides was describing death itself.

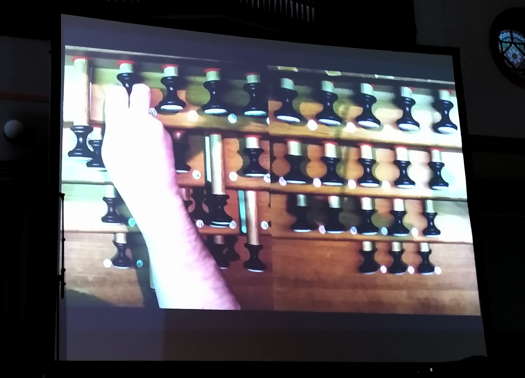

The next work, Quintet (for organ), commissioned specially from Orgelpark, was based on another radical concept. Joining organist Jacob Lekkerkerker at the console of the large Verschueren organ, the four members of Montreal-based string quartet Quatuor Bozzini operated the organ stops.

Video camera setup to create the visual aspect of Kyriakides' Quintet (for organ). Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

Two video cameras, positioned either side of the organ console, were used to project live video onto a large screen on the stage, so that what we the audience saw was up to eight hands pulling out and pushing in organ stops, which was actually happening behind us.

Clemens Merkel, Quatuor Bozzini's first violin, tries his hand at organ registration in Kyriakides' Quintet (for organ) projected live on a large screen at Amsterdam's Orgelpark. Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

What we heard was largely a continuum of long and short organ notes with, superimposed, spoken words and phrases, all concerned with aspects of time, including numbers, from a male voice. (It wasn't made clear whose voice we heard, or whether that aspect of the performance was live or recorded.) The numbers increased upwards from 'one', and the phrases were ordered alphabetically, beginning with 'a decade', 'a few minutes' and 'a lifetime' and ending with 'whenever', 'while away the time' and 'while they are sleeping'. So, in a similar way to the facial expression descriptions of Gaze Units, here we heard announced concepts like 'being late', 'milliseconds', 'speed of light' and 'the turning point', somehow separated from the experience of the organ sounds and of time itself passing.

My experience, and that of several other audience members who I spoke to afterwards, was less memorable than in Gaze Units. The connection, if any, between the video of organ stops being pulled and the spoken sounds we heard, wasn't obvious, and, with a-hundred-and-eight separate spoken announcements, the whole process continued for rather a long time.

Composer Yannis Kyriakides joins Jacob Lekkerkerker and Quatuor Bozzini on the Orgelpark balcony to acknowledge the audience applause at the end of Quintet (for organ). Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

The second half of the concert was more conventional in the sense that Quatuor Bozzini was on-stage, sitting and playing as a quartet for each piece, and the visual media aspect was limited to projections on the large screen at the back of the stage.

The first work, Walls have ears, makes use of the 2011 poem Savaş Zamani (Wartime) by Turkish Cypriot poet Mehmet Yaşin (born 1958). The words describe aspects of the clash between Greek and Turkish culture and language - how, for example, speaking Turkish was dangerous, Greek was forbidden and English remained somehow in the middle. The poem, presumably in English translation, was projected, a few words at a time, onto the large screen behind the string quartet. The music from the quartet, mostly long notes and harmonics, was enhanced by processed digital sound - low throbbing noises which became a kind of rumbling echo, perhaps representing Yaşin's inner voice which, in the words of his poem, 'neither the Turks nor the Greeks could hear'.

For hYDAtorizon, which apparently means 'water rooted', the string quartet was joined by pianist Reinier van Houdt who stood at the piano, plucking strings and playing single notes on the keyboard. This piece was originally for piano only, with four small loudspeakers installed inside the instrument. I assume that the four members of Quatuor Bozzini play the floating, shifting, glissandi that would have originally come from the loudspeakers, and van Houdt picks out single notes to play. Here there's no video projection of any kind - just the floating sounds which, according to the programme note on Kyriakides' website, represent the world view of early Greek philosopher Parmenides, who compared the mind to floating seaweed! This is another work which rather outstays its welcome, as the seaweed continues to float for a quarter of an hour or more. The string sounds sometimes drift into and out of chords, and there's a violin solo for Clemens Merkel at one point, high in the register, before he's joined by second violin Alissa Cheung, then Stephanie Bozzini's viola and finally Isabelle Bozzini's cello.

Pianist Reinier van Houdt and Quatuor Bozzini acknowledge applause at the end of Kyriakides' hYDAtorizon. Photo © 2023 Keith Bramich

For the last piece, Lost Border Dances, Kyriakides returns to his 'shopping list' technique, where a list of words and phrases are displayed on the large screen whilst sound is provided by Quatuor Bozzini and electronics. This time the list is a dance score ... authentic instructions for dancers, such as 'spin right, leaning backwards' and 'count to seven', and the dance movements are converted into musical instructions for the quartet. Hence we saw and read the instructions for the dancers and we heard sounds from the string players, but the dance itself was left to our imagination.

The work began with electronics alone, sounding something like continuous background noise from an old analogue recording. The quartet mostly played short, spiky-sounding phrases, moving later to a section with longer notes. The electronic sounds got louder and noisier, developing into highly processed, high frequency repetitive sounds, then later died away again. In addition to the dance score, the screen also showed a series of coloured areas, at times - a single red colour at the top of the screen at one point, and greens, purples and blues later on. Sometimes there were just coloured areas without any text. The work ends with the on-screen instruction '(Dance may be repeated)'.

In one sense, much of the music in this concert derives from the one 'shopping list' idea, used in a variety of ways. The lengths of some of the works almost put them into the class of installations rather than composed works.

The effectiveness, as I perceived it, varied greatly - absolutely riveting in the opening piece, Gaze Units, and, mostly because of the strength of the poem, fairly powerful in Walls have ears. Although the other works affected me less, it's important to remember that other audience members will have had very different experiences, though, and single phrases such as 'speed of the pendulum', 'lying low' or 'mad scrabble' could set off very different reactions in people's heads.

In his recent work, the composer has been exploring interactive and generative scores, and I suspect that Yannis Kyriakides is definitely a name to look out for in the future.

Copyright © 29 November 2023

Keith Bramich,

London UK