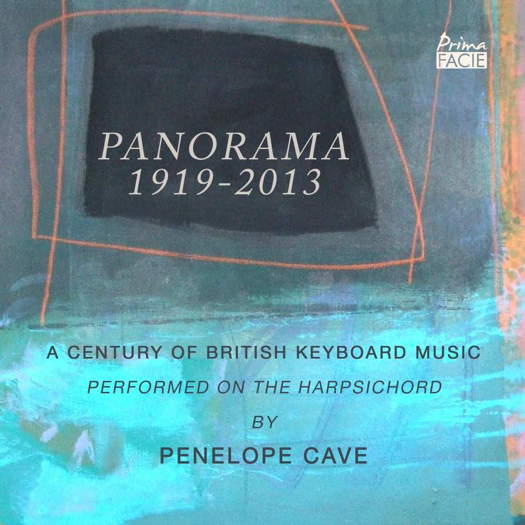

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

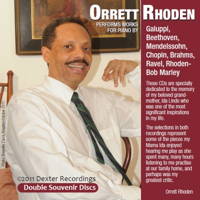

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Most Remarkable - Jamaican pianist Orrett Rhoden, heard by Bill Newman.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Most Remarkable - Jamaican pianist Orrett Rhoden, heard by Bill Newman.

All sponsored features >>

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

Particularly Engaging

MIKE WHEELER listens to Elgar, Anna Clyne, Ravel and Beethoven from Jess Gillam, Ben Gernon and the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

A UK premiere of a recent work by a leading contemporary composer, with one of today's most popular players as soloist, and all going out live on BBC Radio 3. Not a bad start to the Royal Concert Hall's new orchestral season - Nottingham, UK, 5 October 2023.

The BBC Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Ben Gernon (standing in for an indisposed Mark Wigglesworth) opened with a bright, sparky account of Elgar's Cockaigne that tingled with vitality from start to finish.

Ben Gernon. Photo © Simon Annand

It wasn't only the big, fully-scored passages that held the attention. There were delightful moments when solo woodwind lines were heard peeking round corners, and the sheer cheek of the solo clarinet theme (John Bradbury) was unbeatable. The quieter spots - lovers strolling through a park, the inside of a City church - were equally treasurable. There was plenty of building excitement as the band approached. The resulting march is out of the Pomp and Circumstance drawer but, in this performance at least, a whole lot racier. The optional organ part at the end added depth of perspective, rather than mere weight, its initial entry not so much heard as felt.

Elgar and his wife Alice, may have lived in London for a couple of unhappy years, before Cockaigne was written, but the music clearly loves the city to bits. If only more Elgar performances were as uninhibited as this.

Anna Clyne wrote her soprano saxophone concerto, Glasslands, in 2022 for Jess Gillam, who gave the first performance in Detroit in February. In three parts (as Clyne calls them, not movements), its starting point is the banshee of Irish folklore, whose nocturnal wailing is said to herald a family death. Gillam took centre-stage when required, flipping effortlessly from piercing to subtle, while readily taking the more collegial approach with various orchestral soloists, which Clyne maintains is central to her way with concertos. When not letting loose flights of several angry bumble-bees, Gillam entered the calm spaces of her duets with various orchestral players - John Bradbury, again, Jennifer Galloway, oboe, and Alex Jakeman, flute, with equal conviction.

The deep tranquility at the start of Part 2 was well sustained, with Gillam in dialogue with, this time, Peter Dixon, cello, James Opie, viola, Roberto Giaccaglia, bassoon, then a string quartet - leader Zoë Beyers and Glen Perry joining Opie and Dixon. Gillam was still able to fizz into action in a moment, with no sense of dislocation. She was particularly engaging, too, in the jazzy staccato dance that breaks out from time to time in Part 3. Paul Patrick and Geraint Daniel were in joint authoritative charge of the important vibraphone part, here and in Part 1.

Clyne's alert ear for orchestral colour was very much in evidence, just part of what makes her one of the most interesting composers around at the moment. I look forward to hearing the results of her recently-announced three-year residency with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra.

Anna Clyne. Photo © Christina Kernohan

For her encore, Gillam spliced together very effectively two short unaccompanied pieces: Early Morning Melody, by Meredith Monk, and Shine You No More by violinist and leader of the Danish String Quartet, Rune Sørensen. The poised eloquence of the one nicely offset the other's foot-tapping perkiness.

Jess Gillam

After the interval, the original five movements of Ravel's Mother Goose wove their magic once more. Hushed strings created a serious but not solemn atmosphere for Sleeping Beauty's Pavane; Tom Thumb's winding lines sounded plaintive against the pin-point sonorities of the bird-calls. In the gamelan-inspired Petite Laideronette, the orchestral sound was not unduly cushioned, and as a result sounded more like a real gamelan than some performances I've heard. There was further magically soft playing for Beauty and the Beast's gentle waltz, with Bill Anderson's solo contrabassoon phrases stopping well short of caricature. The Fairy Garden flowered both gently and purposefully towards the final outburst.

Outbursts of a different kind characterised the performance of Beethoven Symphony No 5 that followed. There was nothing portentous about the famous opening, Beethoven's marked pauses barely registering amid the coiled, ferocious energy. The plaintive oboe solo towards the end of the first movement was given due space, which served only to emphasise the symphony's astonishing concision. Similarly, the second movement's eruptive climaxes were all the more telling for the quiet, lyrical, even elegant, moments preceding them. The third movement was driven by a nervy intensity, the cellos and basses in the trio section not lumbering, as they sometimes can, but spring-heeled. The quiet reprise of the opening had edge-of-seat tension, and I've not previously been so aware of how much Beethoven's bassoon writing here clearly influenced Berlioz in the finale of his Symphonie Fantastique. The fast tempo adopted for the final movement felt completely right on its own terms, thrilling and exhilarating. My one reservation concerns the flashback to the third movement - spooky, but over a bit too quickly to properly make its mark. The rest of the performance powered ahead, culminating in a clear suggestion of where Beethoven would find himself at the end of Ninth Symphony.

Copyright © 11 October 2023

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK