- Philip Ledger

- St Petersburg

- Canadian

- VJ Day

- Pirkanmaa

- Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Alex Greenbaum

- Oren Fader

VIDEO PODCAST: Find out about composers from unusual places, including Gerard Schurmann, Giya Kancheli, Nazib Zhiganov and Nodar Gabunia, about singing in cars, and meet Jim Hutton from the RLPO and some of our regular contributors.

VIDEO PODCAST: Find out about composers from unusual places, including Gerard Schurmann, Giya Kancheli, Nazib Zhiganov and Nodar Gabunia, about singing in cars, and meet Jim Hutton from the RLPO and some of our regular contributors.

SPONSORED: Vocal Glory - Massenet's Manon in HD from New York Metropolitan Opera, enjoyed by Maria Nockin.

SPONSORED: Vocal Glory - Massenet's Manon in HD from New York Metropolitan Opera, enjoyed by Maria Nockin.

All sponsored features >>

A short night at the opera

The first time I sat dazzled and transfixed by Bartók's Duke Bluebeard's Castle, the fact that the whole mesmerising adventure was done and dusted in an hour escaped my notice. When I subsequently thought about how much Bartók had packed into such a short span of time, it made so many other operas seem almost grotesquely overblown and unjustifiably protracted exercises in beating about the bush in comparison. Furthermore, for all their length, few other operas seemed to say as much or pose as many perplexing, enticing questions about human relationships or the human condition as that magical marriage of Bartók's music and Balázs' words. I presume it is mostly because of the profound impact that Bartók's only opera had and continues to have on me that when it comes to dramatic works for voices and instruments I tend to feel - there are exceptions - that less is more. So if your boss is unwilling to give you the necessary week off work needed to find out what happens after Siegmund sleeps with his twin sister, this week - as a follow-up to yesterday's feature here on Classical Music Daily - I am offering up five operas - in a broad sense of the word - that can be listened to on a work night and still allow you to get to bed before your carriage is turned back into a pumpkin.

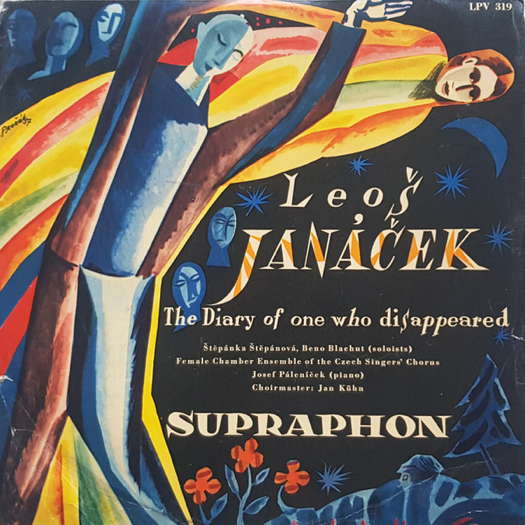

1: Leoš Janáček (1854-1928):

The Diary of One Who Disappeared (1919)

Many may balk at the idea of anything by Leoš Janáček being included in a piece dedicated to lesser-known music, and I take the point on board, but I include this piece here simply because I consider it one of the greatest pieces of music written by anyone anywhere ever and as such I do not feel it has earned anything like the recognition it deserves. This wonder is unique in so many ways, from the forces it requires, its structure, its welding of word and sound, to the atmosphere it creates and the impression it leaves on the listener, at least on this listener anyway.

Right from the first song which describes the young man's initial sighting of the unknown girl and her bottomless dark eyes, there is a foreboding sense of an inescapable abyss opening up which creates a magnetic atmosphere that holds the listener by the throat and never lets up. Its portrayal of Eros as an almost doom-laden malevolent indifferent spirit that possesses him and tears this young man apart from the inside is extraordinarily potent. The torture he goes through because of his desire for her and his corresponding, contrasting wish to do what his parents and upbringing would expect of him is quite harrowing. All the more so because the words and Janáček's setting of them are so deceptively simple. The extremely evocative twelfth song in its haiku-like capturing of mood, moment and meaning is one of the greatest things in all music, and together with the thirteenth makes anything in Wagner's Tristan und Isolde seem like a limp white-coated biology lesson in comparison.

Fate has decreed what the young man must do and there is a terrible sense of loss expressed for what he must abandon in order to follow his fate, a sadness for the misdeeds he carries out upon his beloved family for the sake of his lover, even nature seems to judge him but above all a sense of tremendous liberty in that he doesn't deny his destiny for the sake of the mores of the world in which he grew up. Or is he making a terrible mistake, blinded simply by the natural law of lust? Each listening throws up more questions and conflicting emotions. 'I would kill all the cocks in the world if it meant they would never crow.'

Leoš Janáček: The Diary of One Who Disappeared. © Supraphon Music Publishing

2: Othmar Schoeck (1886-1957):

Penthesilea, Opus 39 (1925)

Apart from being one of the greatest songwriters of all time, not that anybody listens to them, Othmar Schoeck was also an extremely impressive dramatist. His compression of Kleist's unique take on Homer into a one-act whirlwind is a brilliant demonstration of just how impressive. The score is quite extraordinary. I can't think of any other that portrays the fury of battle so effectively. He does this not only through his unique orchestration: ten differently tuned clarinets, two pianos, massed brass and swathes of percussion but also through the stark juxtaposition of tonal centres in the harmonic structure of the piece. This is not just a breathless battle of warriors - men and women - but also of wills. A savage love duel in which kissing rhymes with biting. An immensely intense retelling of Greek epic drama that lasts little more than an hour. Buckle up.

Othmar Schoeck: Penthesilea. © Deutsche Harmonia Mundi

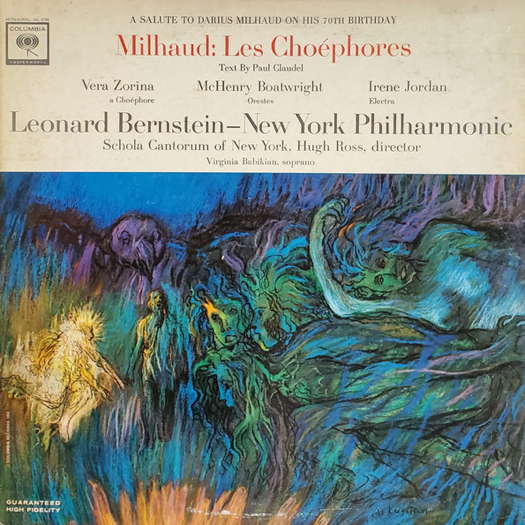

3: Darius Milhaud (1892-1974):

Les Choéphores, Opus 24 (1915)

Darius Milhaud's sheer quantity of music of questionable quality has not done his reputation any favours, but amongst the abundant chaff there is at least a bushel's worth of the finest wheat. This, the central part of his and Claudel's version of Aeschylus' Oresteia, is among his very greatest creations. Its use of declamatory melodrama, typical of much French vocal music, which usually I find quite hard to palate, here seems totally convincing and apposite. Combined with Milhaud's wonderful and novel use of percussion, it only increases the impression that you are actually witnessing an Athenian fifth century BC tragic drama as it may have been rendered at the time. The transparent setting of Claudel's text in Milhaud's unique modal, polytonal, maybe polymodal harmonic writing creates this mysteriously austere, ritualistic atmosphere which remarkably seems as much Ancient Greece as it does early twentieth century Paris. It clocks in at just over half an hour. Not bad for a composer not long out of his teens.

Milhaud: Les Choéphores. Leonard Bernstein - New York Philharmonic.

© Columbia Records

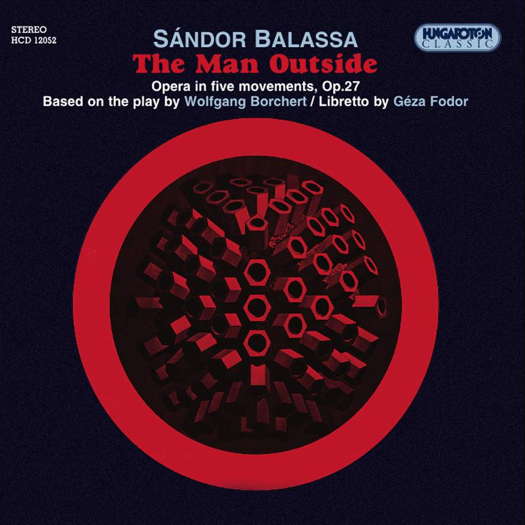

4: Sándor Balassa (1935-2021):

The Man Outside, Opus 27 (1976)

This opera, and Wolfgang Borchert's play on which it is based, serve as a chastening testament. An eyewitness account which all those classical music enthusiasts and critics - who bend over backwards to make excuses for and pleas on behalf of those musicians who were indifferently complicit with or enthusiastically embraced the imbecilic ideology, criminal conduct, perverted practice and degenerate doctrines of the Third Reich - would do well to listen to at least once a day for the rest of their lives. The usual English translation of the title is a poor one as it makes no reference to the word door in the original which is of utmost importance. Outside the Door would be a far better translation. The main protagonist is a German soldier returning home from war. Owing to the fact that his wife left him for another man while he was away at the front, that he is unable to remain deaf and blind to the suffering of others, unable to relinquish his sense of personal responsibility, that he refuses to see art as mere entertainment and a means to make money, that he refuses not to tell the truth simply out of concern that it might be unpalatable or unpopular, that he refuses to live a lie - for all these reasons, all doors remain closed to him, except the gaping door of death. Sándor Balassa's gripping telling of this torrid tale owes something to Brecht, a lot to Wozzeck but more to that whole generation of German youth betrayed, tortured and murdered by their elders.

Sándor Balassa: The Man Outside. © Hungaroton

5: Gerhard Schedl (1957-2000):

Kontrabass (1982)

Although Borchert and Gerhard Schedl were members of different generations and as such had vastly different life experiences, this extremely inventive chamber opera powerfully demonstrates the unexpected, subtle and complicated relationship between the two. On one hand it shows the aching unbridgable gulf of feeling and understanding, even in the case of the most sensitive and sympathetic, between those who experienced the second world war and those who have only known carefree peacetime. On the other it portrays the predicament of those forced to live in this present but who are utterly haunted by and unable to escape the ghosts and horrors of their past; the pain of being a survivor in a world that has seemingly moved on and doesn't want to know.

Österreichische Musik der Gegenwart. Gerhard Schedl: Kontrabass.

© Classic Amadeo

I don't want to speculate as to whether the ghosts of the past played out a terribly tragic twist in Schedl's own life but for whatever reason this extremely talented composer and admired teacher when he was forty-three years old walked into a wood one winter's day with a loaded gun and never walked out.

Copyright © 19 February 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain