DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

- Outhere Music France

- Leroy Anderson

- Eric Van Tassel

- Benno Moiseiwitsch

- Rafael Puyana

- Wu Zuqiang

- Siqian Li

- William Busch: Three Pieces for Violin and Piano

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. An Encyclopedic Recital - Elizabeth Moak plays Judith Lang Zaimont, heard by the late Howard Smith.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. An Encyclopedic Recital - Elizabeth Moak plays Judith Lang Zaimont, heard by the late Howard Smith.

All sponsored features >>

TOWARDS THE UNKNOWN REGION

The late GEORGE COLERICK discusses Ralph Vaughan Williams as writer on music, particularly when he turns his thoughts towards Beethoven's Choral Symphony

Ralph Vaughan Williams - 'RVW' as he was known - and George Bernard Shaw date back some four or five generations, but their musical writings, spanning some eighty years, remain unusually stimulating. Their conflicting opinions on many composers are revealing, and especially over the issue of nationalism in music.

Though a mere sixteen years younger, RVW's published writing dates from his maturity, a time after GBS had completed the bulk of his. GBS the dramatist wrote like a journalist; Ralph Vaughan Williams the composer as a teacher and often like a historian. More than anyone else, he has made me go back, or forward to works which he has presented in an invitingly fresh light.

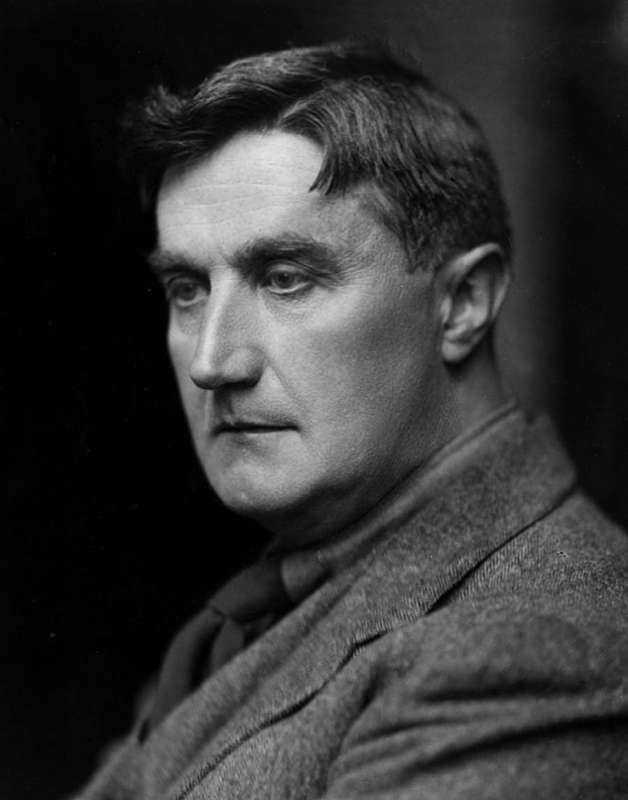

RVW (1872-1958) - portrait by E O Hoppé

A grand-nephew of Charles Darwin and related to the Wedgewoods, he received a classical education and took a history degree at Cambridge. A man of very enlightened social views and a good, relaxing mixer, his broad approach to music is revealed in countless anecdotes, but I particularly like hearing details about the occasion when he gave a street musician a hand in fashionable High Street, Kensington by banging-out tunes on his barrel-organ. The only surprise is that he did not subsequently compose a work for that instrument to which he specially liked to see children dancing. That and the lilt of a chorus joining-in a popular music hall song were among his notions of what composers' 'raw material' should consist.

His teacher, Charles Stanford, whom he also admired as a composer, wanted him to study opera in Italy but in 1896, he made the excellent choice of Berlin for his honeymoon. He then remained there for two terms to study, partly because that was the only city where Richard Wagner was being performed uncut. His reward was to receive more encouragement for his awkward talents from the traditionalist composer Max Bruch than anyone had previously given him. He particularly recalls opera evenings and subsequently wrote more about German composers than any others.

Berlin's Spittelmarkt in 1896

Yet the cult of Wagner at that time was not for long to affect him, whereas J S Bach remained for him the greatest of all influences. He dislikes the recurring fashion for playing such music on 'period' (eighteenth century) instruments. Being born in an age when the piano had to serve so many important functions, he sympathises with Bach for having had to tolerate the nasty jangle of a harpsichord, which could not even sustain a note, and which in the twentieth century was composed for only in special circumstances. Of the traditional eighteenth century instruments, he thought the baroque organ a 'monstrosity' and oboes 'asthmatic'.

Great composers such as Brahms and Wagner do not just pop out of a hat, they come at the end of a period and sum it up. Sometimes the potentially right man comes at the wrong time; Purcell was too early for his flower to bloom fully. Sullivan might have written a Figaro but was held-back by mid-Victorian inhibitions.

As an eighteen-year-old music student, RVW had his wish come true when he began to study under Hubert Parry. When writing in his maturity, he still considered Parry's Blest Pair of Sirens his favourite piece of English music and was absorbed by his Job and De Profundis. Yet he had for some time been baffled at Parry's assertion that Gounod's greatly admired Judex melody from Mors et Vita was 'bad' music, and the theme from the finale of Ludwig van Beethoven's Eroica Symphony 'good'.

He had had to learn to appreciate the greatness in Beethoven's early and middle-period works behind the idiom which he did not find sympathetic; sometimes he associated it with fashionable Viennese salons. Yet he admired the Moonlight and Kreutzer sonatas which many of his English contemporaries had been inclined to criticise as 'in bad taste'. He calls the opus 78 Sonata 'a dreary affair', despite Beethoven's known affection for it.

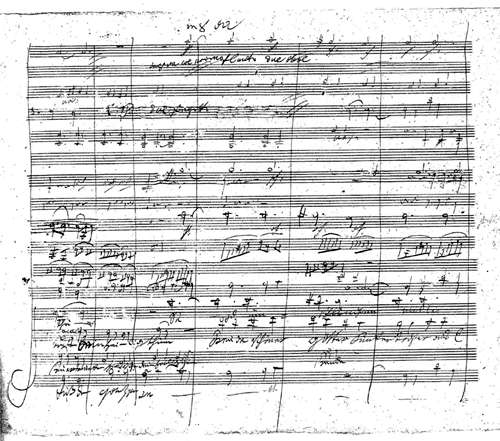

Beethoven in 1815 by J W Mähler

RVW writes at length about Beethoven. It seems to me that he had no difficulty with the late-Beethoven works because they cut through all artifice and prettiness. To critics of the finale of the Ninth Symphony (1824) he suggests that 'good taste' is a poor substitute for the dictates of genius. That movement, in his view, is the noblest conception in a work which ranks alongside the finest of Bach's. If the finale is difficult to perform to perfection, that is partly because conductors approach it with too much anxiety and restraint; it is populist in spirit and if Beethoven had lived a century later, he would have approved of Salvation Army bands. The technical problems are formidable; D major suits the instruments in the melody to Friedrich Schiller's Ode to Joy, but is too high or too low for the chorus, whilst later, holding a high F for twelve seconds is a trial for most sopranos.

RVW dislikes the 'tag' on the end of the Joy theme, finding it quite unnecessary. In fact, it does not appear in the early exposition, though I had always considered it an integral part of the theme, a cheerful rounding off. He does however strongly approve of the 'Turkish Patrol' variation played by the wind band and probably sung by a drunken soldier, in a section referred associated in Schiller's original text with the stars marching across the heavens. Presumably Beethoven's citizen army still marches in 1824 even though Napoleon has finally departed.

Handwritten manuscript of a page from the last movement of the Choral Symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

One of the symphony's innovations is to introduce a 'vulgar' new theme in the final two minutes - drums, cymbals, trumpets, voices, unrestrained jubilation - and RVW considers this coda one of the work's finest inspirations.

He sees the Choral Symphony, not as the perfection of Beethoven's art, but as a great experiment, an adventure towards the unknown region where even he could not see clearly ... seeing as in a glass darkly what no-one has ever seen before or since.

Copyright © 3 January 2023

Estate of the late George Colerick,

London UK