- Busnois

- Gianni Schicchi

- Alceste

- Jonathan Harvey

- Peter Maxwell Davies

- Cheryl Frances-Hoad

- Josefine Winter: Im Buchenwald

- Lisa Bielawa

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

All sponsored features >>

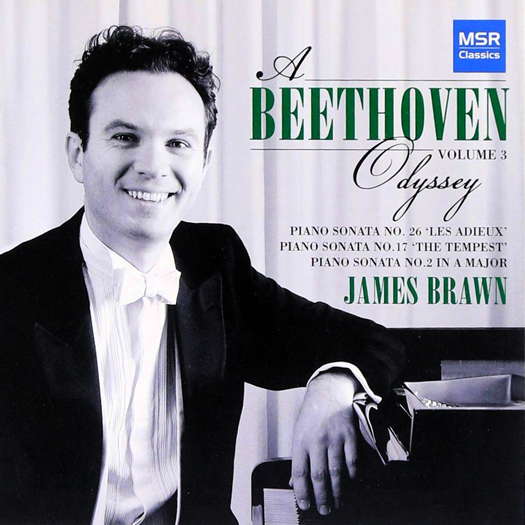

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

Don Carlo in the Mists

GIUSEPPE PENNISI visits Florence for a performance of Verdi's most complex and monumental opera

It was nice to see, on 8 January 2023, the Teatro del Maggio Fiorentino full in every order of seats - about 1,900 - for an afternoon repeat of a new production, the fifth in Florence since 1985, of Verdi's most difficult opera to stage. This was especially so after a few weeks when a different production of the same work, chosen for the inauguration of the San Carlo season in Naples, made a real thud.

Don Carlos (in the French version) or Don Carlo (in the Italian version) is Giuseppe Verdi's most complex and monumental opera, to a libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle based on the homonymous tragedy by Friedrich Schiller. The first performance, in five acts and in the French language, took place on 11 March 1867 at the Salle Le Peletier of the Théâtre de l'Académie Impériale de Musique in Paris. In Italy, the premiere was on 27 October 1867 at the Teatro Comunale in Bologna with Angelo Mariani (conductor), Teresa Stolz, Antonietta Fricci and Antonio Cotogni in the translation by Achille De Lauzières-Thémines and Angelo Zanardini. In 1872, Verdi made some minor changes with the collaboration of Antonio Ghislanzoni, the librettist of Aida. The most important revision was carried out over ten years later and involved the elimination of the original first act. The changes to the libretto were developed by du Locle: the version in four acts was staged at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan on 10 January 1884 in du Locle's revision for the translation by de Lauzières-Thémines and Zanardini.

Two years later Verdi regretted the cuts. The new (third) version of the opera was staged for the first time at the Teatro Comunale Nuovo in Modena, on 29 December 1886, in a new edition in five acts (without the long dances of the original French), which was also published by Ricordi in the reduction for voice and piano. Its writing was quite long and engaged Verdi for over a year. The differences between the three versions are examined in various studies. I prefer the third, that of 1886, because, better than the others, it contains the historical perspective in which the work's complicated plot is inserted. Luchino Visconti in a production for the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, which I was lucky enough to see also in Florence, reads the monumental work as a description of the decline of the Habsburgs of Spain. In my view, that is a correct interpretation.

Of the three versions, the first is almost never staged, also because the performance (with ballets and intervals) would last between six and seven hours; there is a recording dated 1985, conducted by Claudio Abbado and with a stellar cast, but the slow tempos adopted by the conductor make it boring, as well as very long. I remember a mid-seventies production by the Boston Opera brought to Washington where I then lived: Sarah Caldwell produced the Parisian original Don Carlos, with sets and costumes borrowed from the San Antonio Opera and the San Francisco Opera but she was forced to cut the long dances. Even so 'mutilated', it lasted five hours, to which to add intervals for pity for the singers.

The version most often produced in Italy (also for cost reasons), is the second; without the first act. In this Florentine production, this is the chosen version, usually called the 'Scala 1884' version. However, the reference to the youthful dreams of the two protagonists (and to the 'state marriage' imposed against their will) is missing - a theme that resurfaces at various points in the work. Except for the first act of the 1868 and 1886 versions, which is basically a prologue, the action takes place entirely in and around Madrid. It contains the main themes of Verdi's poetics of that period: the relationship between fathers and sons, political power and religion, or rather the difference between churches.

The relations between Emperor Philip II and his only son and, therefore, heir to the throne, Don Carlo, are extremely complicated and do not have a positive solution, as in Verdi's other operas. In order to facilitate peace between France and Spain, Philip II marries Elizabeth of Valois who believed she was engaged (and in love repaid) with the same age infante of Spain, Don Carlo. Philip II also has as his lover the Princess of Eboli, who, instead, is sexually attracted to Don Carlo. In this mess, the situation gets wrapped up. Pushed, in part, by his great friend, the idealist Don Rodrigo Marquis of Posa, Don Carlo tries to escape with Elisabetta to 'a better world', but they are caught and sentenced to death. They are saved by Don Carlo's grandfather and Philip II's father, Charles V, who everyone had given for dead but who had locked himself in a convent and took back 'the mantle and the royal crown' to solve the intricate situation.

Interpersonal relationships are burdened by political ones. Philip II inherited from Charles V 'the empire on which the sun never sets', the largest empire of his time, reaching, in the eighteenth century, an area of 18.4 million square kilometres. Philip II was authoritarian; according to numerous historians, the long decadence of Spain began with his government. In the work, Don Carlo and his associate Don Rodrigo understood the situation, especially with regard to the ongoing rebellion in Flanders. Both to get away from the complicated sentimental plot and to prove his political skills, Don Carlo repeatedly asks Philip II to give him authority to try to solve the problems in Flanders, obtaining increasingly strong denials, and even the death of Don Rodrigo. However, there is something that Philip II and his Court must also submit to: the Inquisition.

Here we have the comparison between two churches, or between two faces of the Roman Catholic Church: the Inquisition and the Convent of San Giusto. The first is impersonated by the Grand Inquisitor, blind, cruel - he enjoys burning at the stake a group of 'heretics' - more powerful than the Emperor, to whom he asks to have Don Carlo killed, and who prostrates himself at his feet to ask 'that peace still lies among us', obtaining as a laconic answer a 'maybe?'. The second is not the bare and poor hermitage of La forza del destino; it is the Church of the Court, animated by choirs of friars. It is a place of redemption, as Charles V says, disguised as a monk at the end of the opera. Questions remain at the end of what is perhaps Verdi's most complex opera. Clear is the desire for a close emotional bond between parents and children (which Verdi lacked all his life because of the premature death of his children) and the rejection of 'political' politics. The relationship with the Church is less evident: in Don Carlo and La forza del destino, 'the Church pomps' and 'the Church power' are rejected. The Convent of San Giusto seems almost inspired by Manzoni's novel I Promessi Sposi.

Within this context, the stage direction, sets and costumes by Luchino Visconti, brought to Florence in the 2004-2005 season, had a meaning: to see the monumental work as the beginning of the end of the Habsburgs of Spain. In this new production, the most questionable aspect is the stage direction by Roberto Andò (and the scenes by Gianni Carluccio, as well as the costumes by Nanà Cecchi and, fortunately few, videos by Luca Scarzella).

The opera is no longer a monumental fresco but an intimate drama of loneliness and incommunicability of the protagonists - Carlo, Elisabetta, Marquis of Posa, Princess of Eboli and Philip II. The action takes place in only one set that, with a few movements of props, become the numerous places of the complex story. Everything is shrouded in thick fog.

Francesco Meli as Don Carlo and Ekaterina Semenchuk as the Princess of Eboli in Act II Scene 1 of Don Carlo in Florence. Photo © 2023 Gianni Carluccio

The acting seems inspired by those of provincial theaters in the second half of the fifties. I will not dwell on other details, for example why the Grand Inquisitor is shown as Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church.

There is an intimate atmosphere in the pit too: Daniele Gatti, who conducted by heart, sometimes crawls the tempo but he is at the helm of the magnificent orchestra of the Maggio Fiorentino which digs into moments of solemnity. The use of the second orchestra, as well as of the brass, in the side gallery gives excellent stereophonic effects. As always, the chorus, prepared by Lorenzo Fratini is excellent - especially in the crowning scene. Another interesting aspect: in this orchestral reading, the work's modernity is felt: few 'closed numbers', recitatives and declamation of great class.

A scene from Act I of Don Carlo in Florence. Photo © 2023 Michele Monasta

As for the voices, Francesco Meli (Carlo) and Eleonora Buratto (Elisabetta) have the perfect touch. Meli's ringing is heard, in the particular Verdi meaning, since the cavatina 'Io l'ho perduta'. Their duets are magnificent: the one in Act IV is poignant.

Francesco Meli as Don Carlo and Eleonora Buratto as Elisabetta of Valois in Don Carlo at the Teatro del Maggio Fiorentino. Photo © 2023 Michele Monasta

Buratto triumphs in the difficult aria 'Tu che la vanità'.

Eleonora Buratto as Elisabetta of Valois in Don Carlo at the Teatro del Maggio Fiorentino. Photo © 2023 Michele Monasta

Ekaterina Semenchuk is a strong-willed and sensual Princess of Eboli, who deftly tackles 'the song of the veil', the Act II duet which turns into a trio, and above all 'O don fatale' in Act III.

Ekaterina Semenchuk as the Princess of Eboli and Massimo Cavalletti as the Marquis of Posa in Don Carlo in Florence. Photo © 2023 Michele Monasta

Mikhail Petrenko is a Philip II more tormented than solemn: well chiseled in the duet with the Marquis of Posa (Massimo Cavalletti), he seems to lose strength in the one with the Grand Inquisitor (Alexander Vinogradov). I think it is largely attributable to the stage direction.

Massimo Cavalletti is a bit disappointing: he knows the role well - I've listened to him several times, in Florence too - but in this production he sings only one evening. The others are entrusted to Roman Burdenko. He did not seem to dominate his stentorian (but poorly modulated) voice - perhaps because of little rehearsal.

In short, there was fog on stage but many lights in the orchestra and voices, so a great success.

Copyright © 10 January 2023

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy