DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Melting Rhapsody - Malcolm Miller enjoys Jack Liebeck and Danny Driver's 'Hebrew Melody' recital, plus a recital by David Aaron Carpenter.

All sponsored features >>

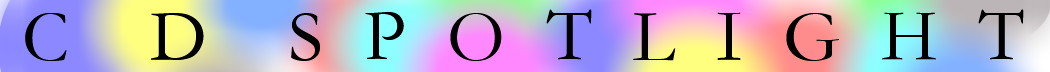

Magnificent Throughout

ROBERT McCARNEY listens to music by Mieczysław Weinberg

'... a wonderful rich ripe legato feel and sound.'

Let's start at the beginning – the cover. I am delighted to say that this CD mercifully sees a very noticeable and extremely welcome change from Deutsche Grammophon's default album 'art'. By that I mean, that for once our eyes have been spared yet another lazy, tacky, predictable, unimaginative and musically irrelevant glorified selfie. Typically – as it seems to me - for their covers, the marketing people at Deutsche Grammophon - during their coffee break - take an artist down to the nearest underground car park, interview room at the local police station or boiler room in their own dungeon, switch on the hair dryer and interrogation lamp and take a few mug shots and then return to their social media accounts. Who was it who thought that a classical music CD cover that looks like a shampoo advert or somebody trying to convince me that I need a mortgage was a good idea? And what possible relevance do these covers have to the musical content and its execution within, which is the raison d'être of their existence?

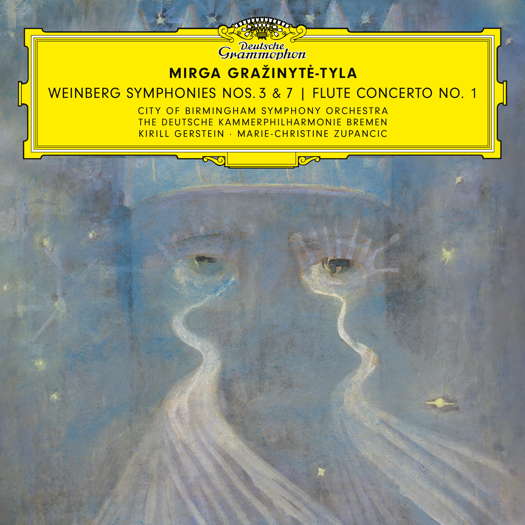

Let's take as a random example the last Deutsche Grammophon CD reviewed on this site: Secret Love Letters. What, pray tell, does that cover have to say about the music of Franck, Szymanowski, Debussy or Chausson or the pertinent recorded interpretations thereof?

Secret Love Letters. Lisa Batiashvili. © 2022 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH

If one didn't already know, you would be totally oblivious to the fact that the lady who adorns this CD, is in fact an extraordinarily gifted violinist. What is this cover trying to say, or trying to sell us exactly? Here's a wild idea, how about for a CD entitled Secret Love Letters how about furnishing the cover with a photo of, all things, a love letter?

The CD under present review is graced with a magically evocative picture by great, and tragically short-lived, Lithuanian artist Mikalojus Čiurlionis. I like to think that the conductor on this occasion, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, was responsible for choosing this most apposite - in that it reminds us of the centuries long connection between Poland and Lithuania - and appealing cover by her compatriot. If that is the case, I hope this will set a precedent for allowing musicians and not marketing people to choose how to decorate their CDs. Maybe the artists themselves do indeed choose these holiday photo style covers. I find it hard to believe but if I am wrong I apologise to the marketing people and direct my plea to the artists involved. If any marketing people or whoever is responsible do read this, for what it is worth, over the decades there are probably a hundred Deutsche Grammophon CDs or more that I have wanted to buy based on their musical content but was unable to do so because I could not bring myself to share my home with all those dire, atrociously cheesy, woefully awful covers. Deutsche Grammophon is not alone in committing this recurring visual travesty. For all record companies guilty of these default selfie covers, please stop. Please use more imagination. Please commission artists to design unique sleeves or use appropriate already existing art or images. Now, let's have some music.

We start with Weinberg's Seventh Symphony which he composed in 1964 for the unusual combination of harpsichord and strings. I can never think of the harpsichord without remembering Weinberg's late compatriot Elizabeth Chojnacka, one of the most extraordinary musicians I ever heard. However this particular piece was inspired by another exceptional figure, namely Andrei Volkonsky. Volkonsky was a harpsichordist, organist, daring composer and all-round general thorn in the side for the social realist police of the USSR. On this occasion the soloist is Kirill Gerstein but bizarrely and unacceptably we are not given any information about him or the other soloist on this CD. A state of affairs made even more egregious by the fact that, rightly, all members of The Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen and the CBSO are named.

The opening adagio sostenuto reminds me, in form at least if not in effect, of the opening palindrome of Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste. It might be fanciful musing on my part but the seeming serenity of the harpsichord solo introduction compared to the rather less serene body of strings may be an analogy of Weinberg the Jewish composer in his predicament facing the implacable might of the Soviet cultural authorities. The five movements are played without a break and the middle three evidence Weinberg's mastery of string writing. Perhaps this has something to do with why I have, as of yet, never been as impressed by any of his symphonies to the same extent as I have been by his string quartets. The playing and recording throughout these movements has a wonderful rich ripe legato feel and sound.

The final movement opens with a high pitched tremolo on the harpsichord which Verena Mogl – the author of the informative but rather brief liner notes – speculates may be a rather literal representation of a ringing telephone; alluding to Stalin or his henchmen's modus operandi of terror. Knowing what I do of Weinberg's weirdness at times and his penchant for quotation and allusion, I can well believe that she is right. Not being one who likes to view music as anything more than music. It is hard to deny that this whole symphony seems to be narrating some kind of story.

Listen — Weinberg: Allegro (Symphony No 7)

(00028948624027 track 5, 0:00-0:54) ℗ 2022 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

His Opus 75 Flute Concerto gives the soloist – on this occasion Marie-Christine Zupancic - far greater scope to shine than was possible for the harpsichordist in the Seventh Symphony, and shine she does. It opens with a proper Allegro molto which calls for some rapid playing from the flautist. Playing at this speed is a far more fraught affair when you are using your own breath rather than your fingers and her breath control and razor sharp articulation I found exemplary. The Largo which comes in the middle couldn't be more different and exemplifies the various facets of the flute. If the first movement was all Tamino, the second is all lounging faun. The last movement has a hesitant, ambling feel which after five minutes Weinberg seems to say – right I had better put an end to this – which he does without any further ado.

Listen — Weinberg: Allegro molto (Flute Concerto No 1)

(00028948624027 track 6, 0:00-0:56) ℗ 2022 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

This recording saves the best for last in the shape of Weinberg's Third Symphony, which, due to the artistic gymnastics required by Zhdanov and his goons, took the normally prolific composer a full decade to complete, reaching its present form in 1959. It starts with an Allegro reminiscent of Schubert's Unfinished mixed with Smetana's bubbling Moldau. Indeed it is in the same key of B minor as the former. From here we pass through folk melodies, martial episodes, mighty climaxes to finish in a wonderfully evocative hushed calm with a final unsettling chord. The whole thing is an absolute masterclass in symphonic writing for full orchestra. Next comes a sprightly scherzo that fizzes along for five minutes of what I imagine is just enormous fun for an orchestra and a conductor up to the task – which she most certainly is on this evidence – to play.

Listen — Weinberg: Allegro giocoso (Symphony No 3)

(00028948624027 track 10, 0:00-0:56) ℗ 2022 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

The adagio shows how, even within more or less strict tonality, Weinberg still manages to create his own harmonic soundworld. We end with, as I suppose had to be the case, a rousing Allegro vivace. There are Mahlerian echoes in the woodwind writing here and although I wanted to write this review without mentioning Shostakovich, it is impossible not to think of his influence especially in this movement, which is not to undermine Weinberg's compositional wherewithal or originality; everybody is influenced by somebody - it is what you do with those influences that counts.

Listen — Weinberg: Allegro vivace (Symphony No 3)

(00028948624027 track 12, 7:26-8:14) ℗ 2022 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

For anyone still unversed as regards the multi-dimensional universe of Mieczysław Weinberg's music, right here and now I can not think of a better place to start than this CD. The playing and recorded sound are magnificent throughout and despite the glaring omissions I mentioned above in the notes, it feels like a proper album. The Third Symphony is probably the showstopper but the elusive Seventh is worth spending more time getting to know better. Finally, to whoever did choose the cover: a sincere thank you.

Copyright © 7 October 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

CD INFORMATION - WEINBERG: SYMPHONIES 3 & 7; FLUTE CONCERTO NO 1