- Carl Reinecke

- Tardebigge

- Carboneu

- Allegri Quartet

- Nigeria

- John Alfred Mandel

- Frank Cooper

- Michael Delfín

SPONSORED: DVD Spotlight. Olympic Scale - Charles Gounod's Roméo et Juliette, reviewed by Robert Anderson.

SPONSORED: DVD Spotlight. Olympic Scale - Charles Gounod's Roméo et Juliette, reviewed by Robert Anderson.

All sponsored features >>

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

Stunningly Staged and Sung

Longborough Festival Opera's 'Die tote Stadt', extolled by RODERIC DUNNETT

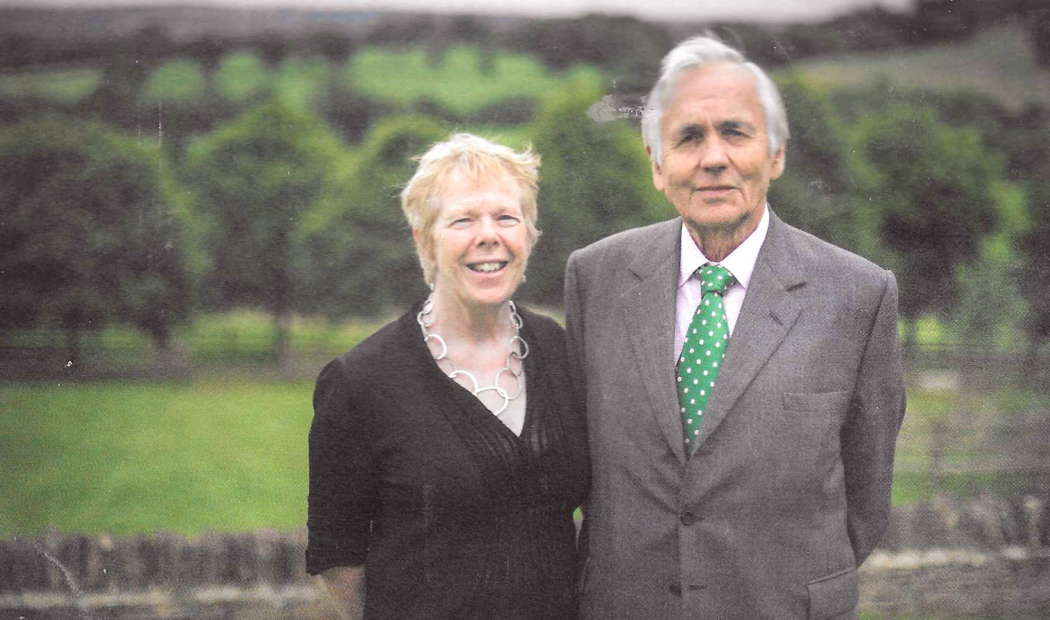

Longborough Festival Opera was launched - one might say took flight – in 1998. Founded and managed by husband and wife Martin and Lizzie Graham – and what a daring, courageous team they proved - it made its artistic mark immediately, with Wagner: a huge success almost instantly to be compared, in location, standards, unique, unpompous invitingness, and its own vivacious style, exuberance and panache – with the other well-known out of London venues: for instance Hampshire's Grange Park, founded that very same year.

Lizzie and Martin Graham, founders of Longborough Festival Opera

And now it has scored a wholly original hit, in the redoubtable Carmen Jacobi's shivering and spectacular – and stunningly staged and sung – production of Erich Wolfgang Korngold's eerie, claustrophobic postwar opera, Die tote Stadt (1920).

Longborough has witnessed, and richly deserved, the non-stop success of its productions of Wagner's Ring (with a host of Wotans), plus a steaming hot Tristan, again directed by Jacobi and universally acclaimed, in 2015 and 2017, Tannhäuser in 2016, Dutchman in 2018. I saw that first Ring, and even with a reduced orchestra and rather brilliant circumscribed surtitles (a series of hints), it was truly exhilarating.

Now it seems possible Longborough's tradition would be not only well preserved, but extended under Polly Graham's patently inspiring (she is that kind of person), fresh and innovative Artistic leadership: by reaching out beyond Wagner in one ideal direction – apart from, say, Mozart or Puccini. Indeed this summer's Die tote Stadt is a resplendent example of what might be possible under, to all intents and purposes, a new regime: neo-Romanticism. (See below, near the bottom.)

It proved a great choice. It requires an electrifying Wagnerian tenor, onstage and visible virtually all the time; a soprano of huge reserves. An amiable baritone of some forcefulness where required; a mezzo (or contralto) exuding humanity, decency and understanding.

All these Longborough gave us. The story – sketched out under a pseudonym by the (at that point) late teenage Korngold and his father, Vienna's famous and prominent music critic - one intriguing detail is that Puccini was a family friend - is both simple and complex. The central character (Peter Auty, a lumbering giant of a sad figure), is obsessed with the memory of his dead young wife. Like Dickens' Miss Havisham he preserves all the mementos of their past together, including especially photographs, in an effectively sealed room.

Candles for a shrine. Paul (Peter Auty) commemorates his dead wife Marie in Longborough Festival Opera's staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

The fact that this obsession runs so deep, and that mourning and grieving have become the sole focus of his now lamentable, weeping existence, accounts for his permanent incarcerated presence onstage. He is his own (or his late wife Marie's) prisoner, shut and locked away in what has become a house of scarcely suppressed horror. His masochism knows no bounds.

Peter Auty as Paul in Carmen Jacobi's stunning staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt at Longborough Festival Opera. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

Peter Auty, a true heldentenor, here in magnificent voice, is made for this role; and at perhaps the right age, just fifty-three, has here made it totally his own, even as the great, perhaps insuperable René Kollo did some forty years ago. Strangely his biography in the impressively packed programme book lists Wagner scarcely at all. This shows his phenomenal versatility in more obvious repertoire - Canio, Des Grieux, Pinkerton - but given the awesome might of his voice and delivery, surely can't be right? A chorister at St Paul's Cathedral, you could imagine his boyish voice having this power and overwhelming command even then; and ever thereafter.

In Die tote Stadt, that gut-wrenching voice has everything: reverence, poignancy, angst, insistence, restlessness, resistance, not so much anger as resentment, occasionally boiling over into violence to mirror his actions (towards his best friend Frank, or his new idol Marietta, whom, in his imagination, he strangles). As for Marie, 'She was beautiful you say? No, she is ... she lives! Soon she will come, come back to me. it's like a miracle, a miracle.' And Paul launches into one of the longest arias – if that's the right word – riddled with imagery, but essentially harping back on the same thing: she is alive.

Frank, kind and caring, is forced to be dismissive, to force upon Paul the truth. 'No miracle: you're worshipping a phantom ... you've been alone too long, you've lost yourself in mourning. You're spellbound by a ghost!'. Even Paul betrays himself: 'I want my dream of her to return'. A dream? Paul is obstinately insisting it's actuality: it's real.

Could an end be in sight? The frantic Paul (Peter Auty) assails Frank (Benson Wilson) iin Longborough Festival Opera's staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

The fact that each is known by just a Christian name – he is Paul (his friend, Frank) – in itself helps the sense that here we have a universal: a psychological type rather than just one individual. This simplification isn't generated by the Korngolds' original source, the novella Bruges la Morte (1892), by Belgian writer Georges Rodenbach, which falls right within the flowering Symbolist genre of that period (Maeterlinck, etc.): elusive, hinted at, indefinable, psychologically probing, often diseased. But it also, as Alexandra Wilson's cogent essay in the programme makes clear, tallies with the both Freudian and to a degree pre-Freudian turn-of-the century preoccupation in Vienna with disturbed, blighted frames of mind.

This Die tote Stadt was a knockout performance. It seems impossible to fault Longborough's boldness and enterprise, which drew full houses, surely proving that where the Graham family leads, their audience will trust and follow.

Indeed, why seek to? There was absolutely nothing to belittle. Jacobi's nervy staging, much abetted by Nate Gibson's claustrophobic, somewhat unearthly designs. Tired monochrome photographs, dominated by an almost grotesquely large painted image - the Virgin, or the Magdalen - of his bewailed Marie, which briefly and genuinely comes alive with the girl Marietta representing the defunct Marie, glare, almost scream from stage left. Candles galore, rendering the 'room' a shrine, inviting Paul to kneel before the image of his dead wife, bring flickering light into this madhouse. This, except that with remarkable restraint and no ostentation, lighting designer Ben Ormerod managed cautiously, tentatively, patiently to penetrate the presiding glooms.

Marietta's altering costumes, one set virtually see through - dressed I think also by Gibson, his fourth production for Longborough - were subtle, desirable, gossamer-like, sometimes all but transparent. Note too Gibson's significant partnering with Polly Graham's 'terrific' staging in London - the Baylis Theatre, Sadler's Wells - of the UK premiere of one of the truly great 'unknown' masterpieces of last century: Simplicius Simplicissimus, by Munich's Nazi-resister Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1905-63). (It was shamefully set in the grim, appalling Thirty Years War, but it could sit as easily in the twentieth century.) This is an opera that, pointedly, poignant, riveting, she could with all her experience, bring to innovative Longborough. Despite all the repertoire and composers I - not wearisomely, or annoyingly, I hope - list below, it could be a great choice. And people would come.

Such was the authority of the two (indeed all) leads, singing in German as lucidly, flawlessly and surpassingly as one could ask, that sometimes you didn't even have to grasp or even focus on the words, or the surtitles: you were so drawn into the aching misery of Auty's Paul, the supportiveness of Benson Wilson as his long-suffering friend Frank - embraced then rejected, then turned to again - or the cheek, flirtation, probing and taunting of Rachel Nicholls' flighty, in his imaginings nearly histronic actress/opera singer Marietta. You could read much of the pained story just from Jacobi's lustrous staging, and from her principals' expressions, all of which suggested the gist of the agonised ongoing happenings.

Rachel Nicholls as Marietta-Marie in Longborough Festival Opera's staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

Claustrophobia: dark, grim, unyielding - we witnessed that in buckets. We felt for Auty's bereft Paul as one might for his wife's death itself. Here, 'shorn of former consciousness of the world outside', was one ponderous, pathetic figure, self-immured, painfully lonesome – one feels in temperament, not just in the present circumstance; what must he have been like to live with when she was alive? And what kind of woman was she? Maria is so reverenced, idolised, sanctified ('Nein, nein: sie lebt'), her indoor shrine like a saint's oblation, one has no real idea, past idea, of the character of the venerated spouse herself.

Paul is, unless he can end this misery, going mad. It is not so much Bruges, with its 'foggy canals, dark medieval streets, sinister cloisters', its stagnant water 'sighing in its age-old canals', all too willing to invoke his ignored surroundings as echoing his painful moods; aligned Bruges is him. Indeed Wilson's Frank agrees with his loathing, near both the start and the close. Yet the fogginess, the dark, the sighing, the stagnation are all his, far more than the derided canalside streets. He invokes the outside to explain, in part, his own destructive, all but lethal, internal shadows.

Benson Wilson as Frank, Paul's faithful but critical close friend in Longborough Festival Opera's staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

Auty's shifting moods - animated, suggestive, pleading – are all captured in the voice. It is indeed a helden- role, and largely this is what he gives us. Paul may subside into hushed reverie, or agonised muttering, but such is his heartache he can as easily – and does – explode into violent, embittered outbursts, almost resentment that his saintly Marie has deserted him. To which add guilt: 'Why am I prowling around her house, longing in remorse?' Notice he says her house. He batters himself with contrition. Every single relic clung onto ensures he can never let Marie go. The obsession is about her; but it's also about things. Are we fascinated, gripped? Yes, we are.

Might not this all grow wearisome? One man's insane blatherings? Even tedious? Strangely, that seems not the case. We are held spellbound, and he won't let us go. Partly this is the father-and-son libretto, of course: it holds up surprisingly well. There may be much repetition, but it is of his sunken mood. Paul entices us into such sympathy, mixed with infuriation that he can't extricate himself from this needless nightmare. Although is it needless? The loss of a partner, a child, a parent can jettison anyone into deepest gloom. It may be draining, throbbing, tormenting, burning, over the top, but the underlying feeling of loss is in its way part of human nature, and for some it can nag away at you, afflict you, harrowingly: if not as excruciatingly as here.

The other thing is the diversions. Partly by a bizarre Pierrot troupe (supposedly arriving by boat: 'Schäume, schäume ... träume, träume') headed in Act II by Victorin (Alexander Sprague) and some kind of Count (Graf Albert) (Lee David Bowen) which emerges and cavorts before him – realistically enough, but all of it a not entirely intelligible part of the dream; amongst whom Wilson (Frank) resurfaces as the actual Pierrot (Canio's role, but benign not sinister).

Rachel Nicholls as Marietta teams up with Pierrot and the Harlequins in Longborough Festival Opera's staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

There's Paul's empathetic housekeeper, Brigitta, utterly outstanding at every appearance, because Stephane Windsor-Lewis brings such a gorgeous mezzo – near enough contralto – to the fore. In her short toings and froings (and it is she who will effectively awaken Paul from his melodramatic extended trance), this Brigitta, loyal despite all, serving Paul now he's dotty as she had previously when all was well, shone like a beacon: she was magnificently understanding – and sane.

Brigitta, the loyal Housekeeper (Stephane Windsor-Lewis), supportive and understanding but flummoxed by her master Paul's eccentric behaviour, in Longborough Festival Opera's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

And above all, the onus of doubling dead Marie and more than a little alive Marietta – an actress both in her stage role (which we don't see) and on this stage (which we do) – fell to Rachel Nicholls, who replaced the original casting, Israeli-Italian soprano Noa Danon. Yet casting is what this production got so right. Nicholls has not only figured as Longborough's Isolde and Brünnhilde (also at English National Opera), but she has taken or is taking her (variously directed) Isolde to eight-plus venues: incredible. It means we were in for a big voice: and we got it. Some wondered whether Marietta's flightiness calls for something less in-yer-face. I, and many, thought her sensational.

And again, Paul (Peter Auty) is inexorably drawn to the seductive Marietta (Rachel Nicholls) in Carmen Jacobi's eerie and mesmerising staging of Die tote Stadt at Longborough. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

It is (the real) Marietta's departure (to rehearsal) that opens the door for Paul's ruling passion to come into its own. The final stages of Act I betray the perils of his state of mind. Out of the - here, very large and oppressive - portrait of Marie he visualises stepping through the frame and into the room his deceased Marie herself. 'Are you still mine? Are you still true to me?' She has left him the braid of her hair which will figure quite grimly before he awakes from his dream. Their love exchange here cries out for a duet, but with most of the interplay being solos, she disappears to be replaced by Marietta, dancing alluringly. The two are patently fused in his mind: 'In you I kissed a dead woman. When I caressed your hair, it was hers.' Yet he despises, but cannot exorcise, his attraction even now to the beckoning actress/dancer.

The painting of Marie comes to life in Longborough Festival Opera's staging of Korngold's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

Quickly we realised that with Nicholls we were in for something pretty stunning. Marietta in the dream may be hurt, irritated, censorious, but also a temptress. It needs a match for Paul, and that's what we got. Yet it varied: both the phantom and the real Marietta can – have to be - coy, evasive; mocking; insistent, demanding; even latterly domineering. It was not just the force and vehemence of the voice when she becomes not complaisant but impassioned that counted. It was her acting, at every turn. Marietta has the misfortune to look, or so he says, like the extinguished wife - is that really what the defunct Marie looked like? - and thus become herself an object of his obsession.

Nicholls, a pretty astounding, as well as gorgeous actress herself, lustable after in her pink, nightie-like dress and clinging scarf (and her several swaps, or partial adjustments, of clothing), makes her imagined Marietta enchant, allure, magnetic, erotic ('Come kiss my lips; ... let me grant you the greatest joy, the soothing cup of forgetfulness'). Likewise sensual 'I'm fond of fun and pleasure ... a dancer, I need that rapture for my art'. Yet strangely intelligent, incisive, teasing. In her enchanting first appearance before all turns to fantasy, trance and delusion, she's young and joyous, almost innocent, extolling flowers and the sunlight that blesses and smiles on them; optimistic ('Hope is rising heavenward'); singing to cheer them both. And as her real self, ecstatic but increasingly sharp in her frustration at the childishness, as she and we see it, of Paul's maniacal fixation. Despite his desire for her - 'You long for pleasures you condemn', she replies - comes his battering reply: 'I loathe and despise you: you have defiled my grief, you have robbed me of my dream ... I have profaned my dead wife'. Voilà. No way out: clearly you can't win.

Truthfully, though why we can't fathom, the real Marietta offers a way out, but both guilt and stunted personality make him resent her all the more. 'You're a cheap fake, a nothing, a shadow ...'. Fearfully, he awaits judgement. And along it comes, in the shape of a handful of censorious black cowled figures - here, the Pierrots shrouded - seeming to rise out of the earth: yet another haunting product of his diseased imagination.

Auty's delivery, singing redolent of a lost soul, urgent, searing, passionate yet terrifying, was typical of the expressiveness he so masterfully generated – yearning mixed with aching and anguish throughout Act I – indeed throughout the opera. He captures the see-sawing moodiness, the terrible isolation, the appalling fixation, and most of the time the voice is high temperature, not quite a shriek but a constant wail, a howl, a yowling sob, an unceasing ululation.

This is the real Paul, and Auty's bawling surely captures the very creation Korngold has plotted in his music. Maybe one could play Paul a different way; conceive of, and sing him as a gentler aching, crazed being. But the figure Jacobi and Justin Brown, thrusting forward the score so vitally and emphatically, and (so crucially) helpful to the voice, allowed him to seem to be as real (or non-real) as could be. He and Marietta matched one another; and it was left to Paul (and Brigitta) to be the soothing presences needed to offset them.

Confrontation or longing - Paul seizes Marietta, whom he will, as he believes, strangle in Longborough Festival Opera's Die tote Stadt. Photo © 2022 Matthew Williams-Ellis

If any opera of that precise era reached out to madness and delirium, and preempts the Korngold, it is probably Franz Schreker's Der ferne Klang (Frankfurt, 1912), in which the equivalent of the unattainable Marie is parodied not by a person, or dead person, but a particular musical formation – theme, pattern, instrumentation – which to his anguish eludes the lead character, Fritz (whom above all his girlfriend, Grete, seeks to free). A further parallel is that Schreker's central act involves a similar kind of, and much longer, Pierrot-like troupe.

Thanks now, perhaps to the vital, inspiring Polly Graham, RADA and WNO trained, and now at Longborough's artistic helm, a first step has now been taken into this kind of Wagner-infused repertoire. Longborough's Die tote Stadt was nothing short of superb; and it could open the door to the sumptuous flood of neo-Romanticism.

Polly Graham, Longborough Festival Opera's artistic director

Some Wagner of course awaits this wondrous Festival: Lohengrin, Parsifal, Meistersinger (in dimensions perhaps not viable), even Die Feen. Examples of post-Wagnerism at Longborough hitherto are Humperdinck (Hänsel und Gretel) and Richard Strauss's Ariadne.

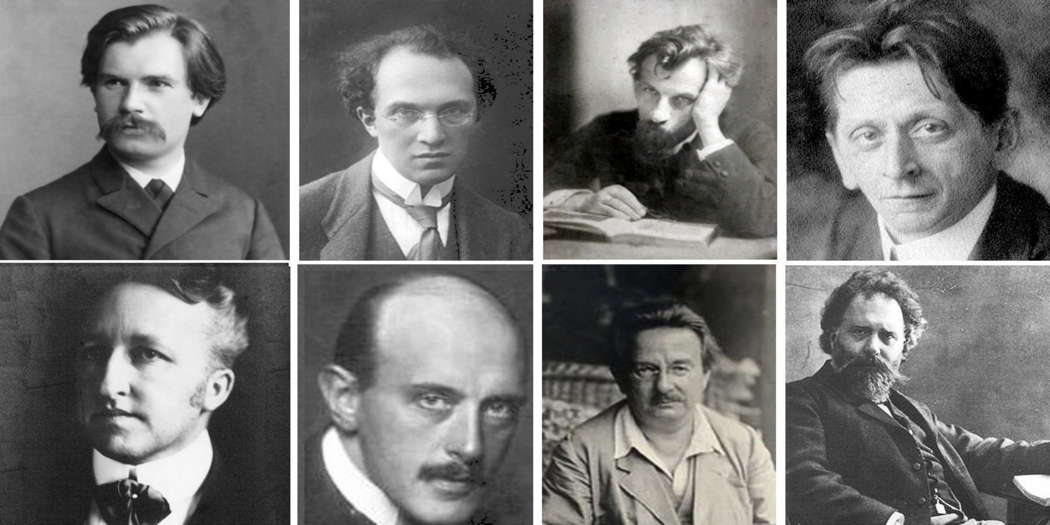

But look who are abiding in the wings: not merely more Strauss (a Garsington special under Leonard Ingrams) and four more Korngold (two one-Acters that could be paired; and two more); but Humperdinck (eight other operas after Hänsel); Schreker (nine), Pfitzner (five); Hindemith (eleven), Zemlinsky (thirteen), Kienzl (ten), Franz Schmidt (two), D'Albert (twenty!), Krenek (twenty-one) and Berg. Even Siegfried Wagner (eighteen)! Any one of which could flourish under the leadership of Longborough's Wagner supremo, Anthony Negus, or indeed the present Korngold's conductor, Justin Brown.

Eight great neo-Romantic composers. Top (left to right): Eugen d'Albert, Franz Schreker, Hans Pfitzner and Alexander Zemlinsky. Below: Siegfried Wagner, Max von Schillings, Franz Schmidt and Wilhelm Kienzl.

And one great thing about this latest, tellingly full-house Korngold is that it shows how those audiences will follow, have confidence in, fully trust wherever Longborough leads. True, there have been, probably have to be, some more hackneyed crowd pleasers - Carmen this year plus in 2006 and 9, well staged snippets of Verdi, all Mozart's da Ponte masterpieces, plus umpteen Schikaneder Flutes. But maybe they're not entirely needed now – most can be seen elsewhere. One wants to focus on what makes Longborough special. So very special.

The Opera House at Longborough

And the Orchestral playing? Well, could it be better? It can almost be taken for granted what extraordinary wonders the Longborough in-house regular orchestra produces. If Auty's Paul had a minefield to cross, requiring endless memory not just of words and music, but moves, gestures, moods, intonation, facial agonies, this orchestra had a joyous field day with this dazzling music, but also a nightmare of complexity to master. Celesta, harp, intricate woodwind emerged with some frequency. Martin Graham some years ago enlarged his orchestra pit - not once but twice. The acoustic is a miracle. In The Ring, for example, stage and pit harness like wholehearted, thirsty siblings. Visit Longborough in season, under Anthony Negus especially, and you are guaranteed that perfect match, instrumentalists and singers. Korngold expounds some massive full, or near-full, orchestral sweeps. They came off grippingly; as did a sombre marching sequence; and at one point the score almost turned into Lehar. Brilliant.

One thing that makes this wonderful company (and venue) special is the growth and flourishing of Longborough Youth Opera, started in 2006. It's typical of this sparkling ensemble - its marvellous, beautifully evolved location from the outset sits in Gloucestershire, with a sensational valley and hillside view - that it has not only engendered a youth production annually, but that it puts youth up front. The young people's productions not just featuring but shining as an important, not merely an additional, part of each main season have, from the very start, astonished by their intelligence, precision, invention, insight, imaginative staging, vivid concept, and amazingly promising young performers.

Inspiredly launching them into Baroque opera has been one of their triumphs. Rinaldo, Xerxes, Alcina – all Handel - have been among the toughest enterprises that emerging, always promising youthful performers can assay. Add Cavalli. Add perhaps the most challenging and demanding of them all, Monteverdi's Poppea. Here are experiences that will last them for a lifetime.

It's impossible to praise this company, with all its sense of adventure, its flair, its intimacy, its magnificent quality on all fronts, too highly to visitors not just from the UK, but from abroad - the United States, Canada, Europe and across the world. If you're exploring England in June and July, make Longborough Festival Opera one of your most exciting calls. You won't be disappointed.

Copyright © 15 July 2022

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK

ARTICLES ABOUT LONGBOROUGH FESTIVAL OPERA