- Alice Josephine Pons

- cpo

- John Towner Williams

- Philip Arnold Heseltine

- María de Buenos Aires

- Grigoraş Dinicu: Hora staccato

- Lisa Bielawa: Centuries in the Hours

- Anna Thorvaldsdóttir: Ubique

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Unjustly Neglected - In this specially extended feature, Armstrong Gibbs' re-discovered 'Passion according to St Luke' impresses Roderic Dunnett.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Unjustly Neglected - In this specially extended feature, Armstrong Gibbs' re-discovered 'Passion according to St Luke' impresses Roderic Dunnett.

All sponsored features >>

VIDEO PODCAST: Women Composers - Our special hour-long illustrated feature on women composers includes contributions from Diana Ambache, Gail Wein, Hilary Tann, Natalie Artemas-Polak and Victoria Bond.

VIDEO PODCAST: Women Composers - Our special hour-long illustrated feature on women composers includes contributions from Diana Ambache, Gail Wein, Hilary Tann, Natalie Artemas-Polak and Victoria Bond.

Symbolism and Realism

MIKE WHEELER experiences Opera North's new production of Verdi's 'Rigoletto'

Opera North's new production of Verdi's Rigoletto is boldly imagined, even though not everything comes off.

We start with Rigoletto himself, during the Prelude, in glittery dinner-jacket, in front of a dressing-room table with its mirror surrounded by narrow strip lights. He is being prepared for, presumably, that evening's appearance as the Duke of Mantua's jester, by two figures in completely white eighteenth-century costume. We see them again later, and the strip lights also return, to play a major role in Howard Hudson's effective lighting, complementing Rae Smith's designs.

Director Femi Elufowoju jr homes in on Monterone's curse as the main plot driver, and also uses the casting of black singers – as Rigoletto, Gilda, Monterone, and Marullo, one of the courtiers – as emblematic of 'otherness', drawing on his Nigerian heritage to place the curse in a culture where it would have much greater resonance than for the party animals of the Duke of Mantua's court.

Roman Arndt as the Duke of Mantua, Eric Greene as Rigoletto, Themba Mvula as Marullo, Ross McInroy as Count Ceprano and Campbell Russell as Borsa, with the Chorus of Opera North, in the opening performance of Opera North's production of Verdi's Rigoletto at Leeds Grand Theatre on 22 January 2022. Photo © 2022 Clive Barda

The problem is that, in the theatre at least, symbolism and realism generally make for an uncomfortable mix. When Gilda is reunited with Rigoletto after being abducted, she appears in a virginal lacy wedding dress, escorted by those eighteenth-century figures in white, which jolts us momentarily into the world of Der Rosenkavalier.

Eric Greene as Rigoletto and Jasmine Habersham as Gilda in the opening performance of Opera North's production of Verdi's Rigoletto at Leeds Grand Theatre on 22 January 2022. Photo © 2022 Clive Barda

The intended comic moments – a pizza delivery for the Count's guards arriving at the end of scene 1, two police officers failing to prevent Gilda's abduction, Hazel Croft's pistol-toting Giovanna – simply misfire. As Monterone, Sir Willard White - there's luxury casting for you - is resplendent in a Nigerian tribal chief's costume – but even as he is being led to his execution?

Willard White as Monterone in the opening performance of Opera North's production of Verdi's Rigoletto at Leeds Grand Theatre on 22 January 2022. Photo © 2022 Clive Barda

His sudden reappearance at the very end of the opera as Rigoletto recalls the curse, is a striking visual coup, but adds nothing dramatically.

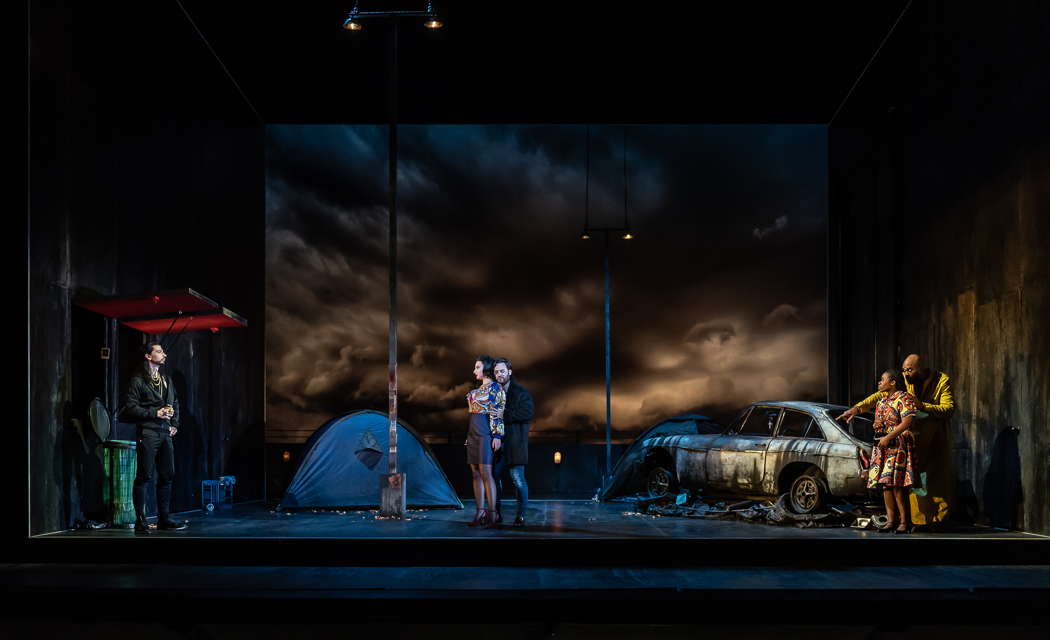

Act III is played out on a patch of waste ground with a pizza shack doing duty for the inn (and which presumably supplies the delivery in Act I), a tent - the scene of Maddalena's seductions - and a burnt-out car which has no other function than to add to the dismal setting. The backdrop's nocturnal storm-clouds, though, are highly atmospheric.

Callum Thorpe as Sparafucile, Alyona Abramova as Maddalena, Roman Arndt as the Duke of Mantua, Jasmine Habersham as Gilda and Eric Greene as Rigoletto in the opening performance of Opera North's production of Verdi's Rigoletto at Leeds Grand Theatre on 22 January 2022. Photo © 2022 Clive Barda

Roman Arndt makes the Duke of Mantua both personable and irresponsibly self-centred. Both 'Questa o quella' and 'La donna e mobile' project a lack of awareness of the havoc his playboy lifestyle leaves in its wake. Eric Greene pinpoints Rigoletto the professional entertainer, and captures the angst of his private life, though some of his physical movements verge on overacting - this is also true of the Duke's courtiers. Jasmine Habersham's Gilda is not merely innocent, but appears to have regressed to (or never left) a state of infantile dependency, an indictment of Rigoletto's over-protection, no doubt; she appears to live in a picture-book fantasy-world represented by a kind of Rousseau-esque jungle. 'Caro nome' – agile, bright-voiced – is all sweet naivete. Callum Thorpe brings a really dark tone to the role of assassin-for-hire Sparafucile, all the way down to some ink-black bottom notes. Alyona Abramova does as much as anyone can with the limited role of Maddalena.

Callum Thorpe as Sparafucile and Alyona Abramova as Maddalena in the opening performance of Opera North's production of Verdi's Rigoletto at Leeds Grand Theatre on 22 January 2022. Photo © 2022 Clive Barda

Conductor Patrick Milne, deputising for Opera North's Music Director Garry Walker for this and a previous date in the run, had the Verdian style at his finger-tips; orchestra and chorus responded with all the panache we've come to expect from the company's previous Verdi stagings.

Copyright © 21 March 2022

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

MORE ARTICLES ABOUT VERDI'S 'RIGOLETTO'

ARTICLES ABOUT NOTTINGHAM'S THEATRE ROYAL