- William Glock

- Daniel Jones

- Kentish Opera

- Gerald Moore

- Gerhard Schedl

- Simon Keenlyside

- Pictures at an Exhibition

- Andrew Arceci

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The Creative Spark, including contributions from Ryan Ash, Sean Neukom, Adrian Rumson, Stephen Francis Vasta, David Arditti, Halida Dinova and Andrew Arceci.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The Creative Spark, including contributions from Ryan Ash, Sean Neukom, Adrian Rumson, Stephen Francis Vasta, David Arditti, Halida Dinova and Andrew Arceci.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. A view from the pit - John Joubert's Jane Eyre, praised by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. A view from the pit - John Joubert's Jane Eyre, praised by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

Simply Outstanding

MIKE WHEELER is impressed by performances of Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky and Myroslav Skoryk from Patricia Kopatchinskaya, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

This was bound to be a highly charged occasion – Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, UK, 5 March 2022.

As Stephen Maddock, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra's CEO, said in his measured, eloquent spoken introduction, none of the shocking events in Ukraine are the fault of the Russian people, or of Russian artists who have publicly distanced themselves from the actions of their government, or of Tchaikovsky or Stravinsky, the composers represented on the programme. And indeed no apology was needed for going ahead with the main programme as planned.

Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet was simply outstanding. Clearly, the CBSO and conductor Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla felt not the slightest temptation to treat it as just an orchestral showpiece, but dug deep into its expressive world. The chant-like music representing Friar Laurence was taken at a steady pace, highlighting its elegiac character. The first appearance of the fight music was vivid and tightly rhythmic. Rachael Pankhurst's cor anglais brought a plangent quality to the love theme, and the nocturnal music seemed to hover around it in both stillness and expectancy. The fight music's full fury was kept in reserve for when it really mattered, as was the love theme's full expansiveness. The final chords hammered home what, for all its familiarity, remains a shocking tale.

Patricia Kopatchinskaya's arrival on stage in a vivid, multi-coloured dress was, in itself, enough to move the evening on to its next stage. Throwing herself into the solo part of Stravinsky's Violin Concerto, she brought huge vitality to the role, and the orchestra matched her approach, with clear, open textures. Indeed, if any of the great twentieth-century violin concertos encourages soloist and orchestra to share a collegial approach, it's this one. In the two central movements an apt balance was struck between poise and serenity on the one hand, and lively surface activity on the other. In the concluding 'Capriccio', Kopatchinskaya's series of duets with various orchestra principals was a delight, not least that with the orchestra's leader, Eugene Tzikindelean, where Stravinsky pays conscious homage to J S Bach's Concerto for two violins. The increase in speed at the start of the coda hinted at something more elemental.

Patricia Kopatchinskaya, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla and the CBSO sharing the applause at the end of Stravinsky's Violin Concerto at Nottingham Royal Concert Hall

One thing you can be sure of when PatKop (as she is known) is on stage – any encore she comes up with is going to be unpredictable, to say the least. Returning after her first bow, she went over to the orchestra's woodwind section and brought principal clarinettist Oliver Janes forward to join her in a quirky duet of her own making (if I understood her spoken introduction correctly), at one point pairing clarinet multiphonics with violin sul ponticello writing. It was a deliciously surreal few minutes.

Moldovan-Austrian-Swiss violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaya (born 1977). Photo © Marco Borggreve

The fanfare that opens Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony has rarely sounded quite so stern in my experience. It launched a performance that, like that of Romeo and Juliet, took nothing in this much-played work for granted. The clarinet solo that follows after the music quietens down felt vulnerable and withdrawn. Tchaikovsky's daringly telescoped recapitulation had real shock value, and the increasing urgency of the fanfare's returns hit home.

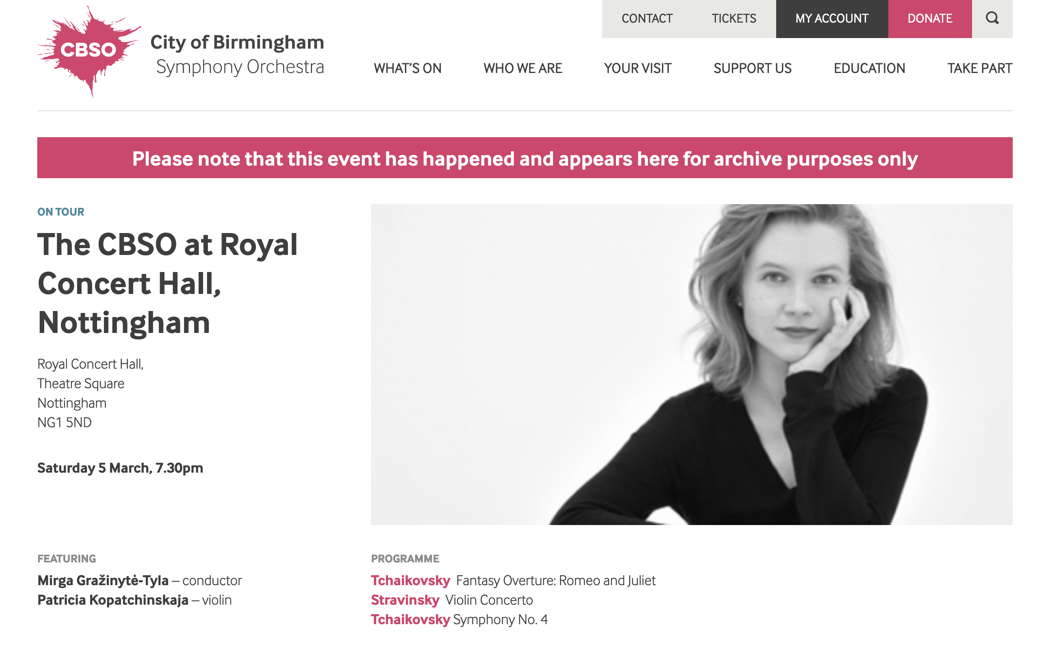

CBSO online publicity for the 5 March 2022 Nottingham concert, including a portrait of Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla

After that, the slight matter-of-fact-ness of Steve Hudson's oboe solo at the start of the second movement was just what was needed. The orchestra's response conveyed a sense of weariness, in contrast to the almost jaunty character of the quicker music later, while the ending verged on the motionless. The pizzicato opening of the third movement bubbled softly at the edge of audibility; the woodwind passages danced vigorously, moving seamlessly into the brass march, which was kept taut and clipped. After the finale's initial eruption, the ebb and flow of tension was handled with exemplary control. The climactic return of the first movement fanfare was not so much a shock in itself, but that was certainly what registered in the aftermath. And as it all started to pick up again, it hurtled to its ambiguous conclusion – defiant, uncertain, celebratory: all of these and more.

Afterwards, the orchestra played Melody by Ukrainian composer Myroslav Skoryk. Its simple directness spoke volumes, as did the several seconds of silence at the end.

Copyright © 16 March 2022

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT UKRAINE

CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT RUSSIA