- fioritura

- John Towner Williams

- Anthony Davie

- Eugene Alcalay

- North Korea

- Robert King

- Ian Buckle

- Roger Sessions

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

Káťa Enthralls Rome

GIUSEPPE PENNISI experiences a Janáček first performance in Italy's capital

It took more than a hundred years for Káťa Kabanová to arrive in Rome. It finally came to Teatro dell'Opera on the evening of 18 January 2022, and not to a very full house due to the pandemic. After about two hours of tight performance, the opera was greeted with great enthusiasm by the audience: applause and acclamations. In recent years, I have seen, heard and reviewed it in productions at the Massimo Bellini in Catania, at the Regio in Turin and at the San Carlo in Naples. I reviewed the last two productions in Music & Vision Magazine.

Rome has always been stingy with Leoš Janáček. Of the Moravian composer's seven absolute masterpieces, Teatro dell'Opera has only staged his first opera, Jenůfa, in 1952 and 1976, while other Italian opera houses have presented, over several years, almost complete cycles.

Janáček is still little known to the Italian public, despite being, with Richard Strauss and Benjamin Britten, one of the twentieth century's greatest composers of musical theatre. Born in 1854 in the same town as Sigmund Freud - Příbor in Moravia, he lived almost all his life in Brno, capital of a region then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and today a southern region of the Czech Republic. Brno is about halfway between Vienna and Krakow - the heart almost of that area of Central Europe where the Great War brought the greatest changes to geographical and political boundaries. For decades, Janáček was essentially a teacher and a very religious man who composed mainly music of the spirit or inspired by local traditions.

When he was about fifty years old, in 1904, almost simultaneously with the world premieres of Puccini's Madama Butterfly and Salome by Richard Strauss, Janáček's first masterpiece Jenůfa had its debut in the tea room (adapted to be a theatre) of Brno's largest café. Today the city has three theatres, of which the largest, a 1,300 seater, bears the name of the composer. Jenůfa had been rejected by the National Theatre in Prague, where it was performed only in 1916 after major alterations imposed by censorship. Jenůfa became a European success following performances in Vienna in 1918 (just as the Empire was on the verge of collapse), in Max Brod's translation into German - the language in which Janáček's works have been performed for decades, outside Moravia. Janáček lived until 1928; in the last phase of his life, in a rapidly transforming Europe, he received well-deserved awards - an honorary degree and admission to the Prussian Academy of Arts.

Although, among the musical 'schools' of little Brno, he considered himself close to the Russian one, he developed a very modern language that was understood outside Central Europe only after the Second World War, thanks to conductors such as Charles Mackerras, James Conlon, Lothar Koenigs, David Robertson, and Marco Angius in Italy. In the New York of the 1970s, Janáček's works found a home at New York City Opera, considered between the experimental and the popular, not at the Metropolitan.

In Italy, Janáček's fortune was late. The chamber music and the Sinfonietta were performed, but it was not until 1936 that Jenůfa was first performed on the radio, and in 1941 it was staged at La Fenice. Only in the 1980s and 1990s were the operas performed in the Moravian language (with the essential help of surtitles) and in critical editions.

There are two characteristic aspects of Janáček's musical theatre, both of which are well captured in Káťa Kabanová and highlighted in this production. In the first place, as his compatriot Milan Kundera points out, the coexistence of several contradictory emotions in very limited spaces creates original semantics in which there are, in parallel, 'the unexpected contiguity' and the 'polyphony' of emotions. Secondly, there is a musical structure based on the alternation of different and contradictory fragments in the same movement (as well as insistent repetition, as will happen later in twelve-tone music), with the inclusion of lyrical abandonments only at certain especially liberating moments (as in the last scene of Káťa Kabanová). Even the tempos and metres alternate with unusual frequency, breaking with the emotional unity of the movements of nineteenth-century music.

This requires a conductor who knows how to blend styles of the early twentieth century with a strong expressionistic charge and styles of contemporary music and twelve-tone music. In the voices, the melody of speech is accentuated with occasional arioso (such as that of the protagonist in the third act of Káťa Kabanová). The treatment of the orchestra is very modern: the ensemble is very large - at the Teatro dell'Opera, part of the orchestra was in the boxes of the first tier - but it is treated as a large chamber ensemble in which instrumentalists or groups of instrumentalists dialogue with each other and often have the role of soloists.

Janáček's operas are usually short - three acts in about a hundred minutes - and strongly theatrical. Káťa Kabanová deals with a provincial affair: the short story of a rich old mother, obsessive towards her son and daughter-in-law (induced to take her own life). The plot not only summarizes the hypocrisy of a society in a century that features the progressive and tiring liberation of women from a subordinate condition. In a small bigoted town, dominated by her mother-in-law Kabanicha (intent, between one prayer and another, in sexual games with the merchant Dikoj), Káťa has a weak and perhaps impotent husband, Tichon, and she is secretly in love with the handsome Boris. Her best friend, Varvara, has a fresh and full love-sexual relationship with the young chemistry professor Kudrjás. During the absence of Tichon on a business trip, Varvara gives Káťa the key to the place where she meets with Kudrjás. We will never know if the relationship between Káťa and Boris goes beyond the Platonic. The remorse, however, is such that on the return of Tichon, and during a summer storm, Káťa confesses that she is an adulterer. She finds relief only by throwing herself into the Volga, while Kabanicha thanks those present for the collaboration given to solve the case caused by the confession of her daughter-in-law. The village returns to the bigotry of all times.

The opera requires a large cast - many are merely secondary characters. Its protagonists are singer/actors who sing perfectly in the Moravian language. Janáček also has a distinct preference for dramatic sopranos, mezzos and tenors with a centre register.

The Rome staging has been co-produced with the Royal Opera House Covent Garden in London. The production, directed by Richard Jones, won the Olivier Award in 2019 for Best New Opera Production. It was supposed to be staged in Rome in the 2020 season that was largely cancelled due to the pandemic. Sets and costumes are by Antony McDonald, lighting by Lucy Carter and choreography by Sarah Fahie. A bare and clear set brings the drama to our days. With few scenic elements, and a lot of acting, the story takes place in a degraded environment, almost a suburb where the myths and rituals of the petty bourgeoisie are accentuated: the world surrounding Káťa (including Boris himself) destroys her. One perceives the social conflicts of an authoritarian world and the inner dramas of the protagonist until the final tragedy.

The Teatro dell'Opera orchestra conducted by the American Robert Robertson is excellent. Based on Charles Mackerras' critical edition, instrumentalists and groups of instrumentalists dialogue with each other as soloists and give a dark colour to the tragedy, highlighting the bright moments in the Act II scenes between the two young couples. The choir, led by Roberto Gabbiani, is, at some moments, the background to the tragedy's development.

Corinne Winters in the title role of Teatro dell'Opera di Roma's Káťa Kabanová. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

Among the voices, the protagonist stands out: Corinne Winters is an absolute soprano who faces an impervious role easily, passing from lyrical moments to others of high drama, and she shows great theatricality.

Corinne Winters in the title role of Teatro dell'Opera di Roma's Káťa Kabanová. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

As often in Janáček, there are two tenors, with slightly different timbres. Lyrical, and slightly sensual, Charles Workman (as Boris Grigorijevič) is a versatile American tenor who in his thirty year career easily passes from Mozart to Wagner.

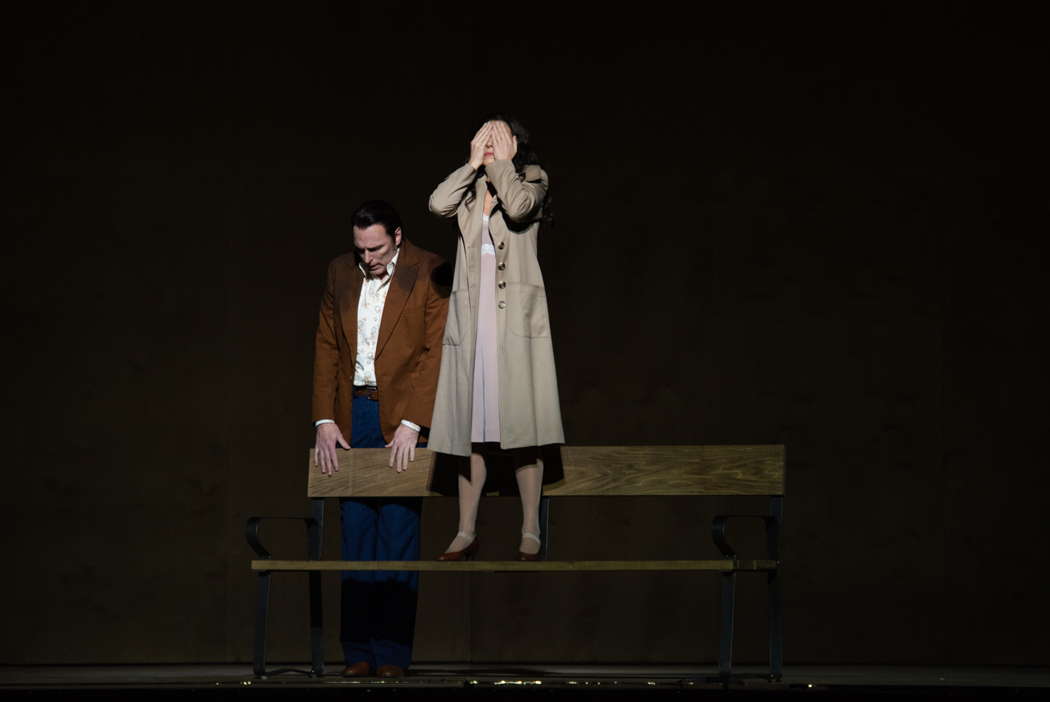

Charles Workman as Boris and Corinne Winters in the title role of Teatro dell'Opera di Roma's Káťa Kabanová. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

Julian Hubbard (as Tichon Kabanov), back from his recent Roman success as Cassius in the inaugural Julius Caesar and above all of the Palermo Parsifal of 2020, both reviewed here, was a bit burnished. The bass Stephen Richardson, who had sung in Rome in Billy Budd in 2018, is the corrupt Dikoj. Mezzo Susan Bickley is the ugly Marfa Kabanová. Sam Furness and Carolyn Sproule are the fresh young lovers Kudrjaš and Varvara, a ray of light in this obsessive and black climate of tragedy.

Carolyn Sproule as Varvara and Corinne Winters in the title role of Teatro dell'Opera di Roma's Káťa Kabanová. Photo © 2022 Fabrizio Sansoni

Lukáš Zeman is an effective Kuligin.

On stage there are also young graduates from the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma's Fabbrica Young Artist Program: Angela Schisano as Fekluša and Sara Rocchi as Glaša.

Copyright © 20 January 2022

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy