- Glazunov

- Robert Harbinson Bryans

- Kaikhosru Sorabji

- Michael Oliver

- Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt

- C P E Bach

- Vector Wellington Orchestra

- Ravel: Pavane pour une infante défunte

A MIRACLE IN NEW YORK

Piano Lessons in the Time of Covid (pace, Gabriel García Márquez), by GLORIA DEVIDAS KIRCHHEIMER

You remember those movies from the forties about reporters working late into the night, their typewriters and desks lit only by a gooseneck lamp with a rounded green glass shade? That's been my piano lamp for decades, sitting on top of my tall 1880 upright Steinway piano. I've seen the date behind the front panel which the tuner removes when he comes to service it. I call it my dowager instrument, one of my most cherished possessions. It has ivory keys - how rare is that?

The lamp has to be placed just so in order to cast almost enough light over two pages of music. The base of the lamp is made of extremely heavy brass. The gooseneck is flexible, but watch out! If you tilt it too far forward, the lamp might tip over. That is why there is always a heavy old-fashioned iron right on top of the electric wire as close to the base as possible, to prevent any accidents.

In the course of human events, one's eyesight begins to weaken and so I have had to shift the lamp's position occasionally, always careful to support the fixture with one hand as I move it with the other.

Alas, calamity struck one day. I moved the lamp which slipped out of my hand and crashed down onto the keyboard before continuing its downward journey to the piano bench. The curved glass shade did not shatter. The only damage - the only damage? - was the destruction, the demolition of the key of D an octave above middle C.

Its demise was not visible since the ivory was not even cracked, but it had lost its sound. Depressing the key elicited nothing. Since the pandemic precluded making an appointment with my piano tuner I was compelled to continue practicing without the use of that key. I felt like those writers who have written tour de force novels omitting one vowel or consonant throughout the work and being applauded for their originality.

I searched for consolation in the midst of my setback and in full pandemic mode. Anything to calm me down. In addition to making airplanes out of the newspaper or baking a loaf of sourdough bread, the New York Times advised me to listen to five minutes of Beethoven. Just which five minutes were they suggesting that did not have my silent D in it? I consulted with my piano teacher. Could she recommend pieces that left out that note, or could I substitute the D one octave lower for the moribund key? Perhaps, she suggested, I could hum the note when it occurred?

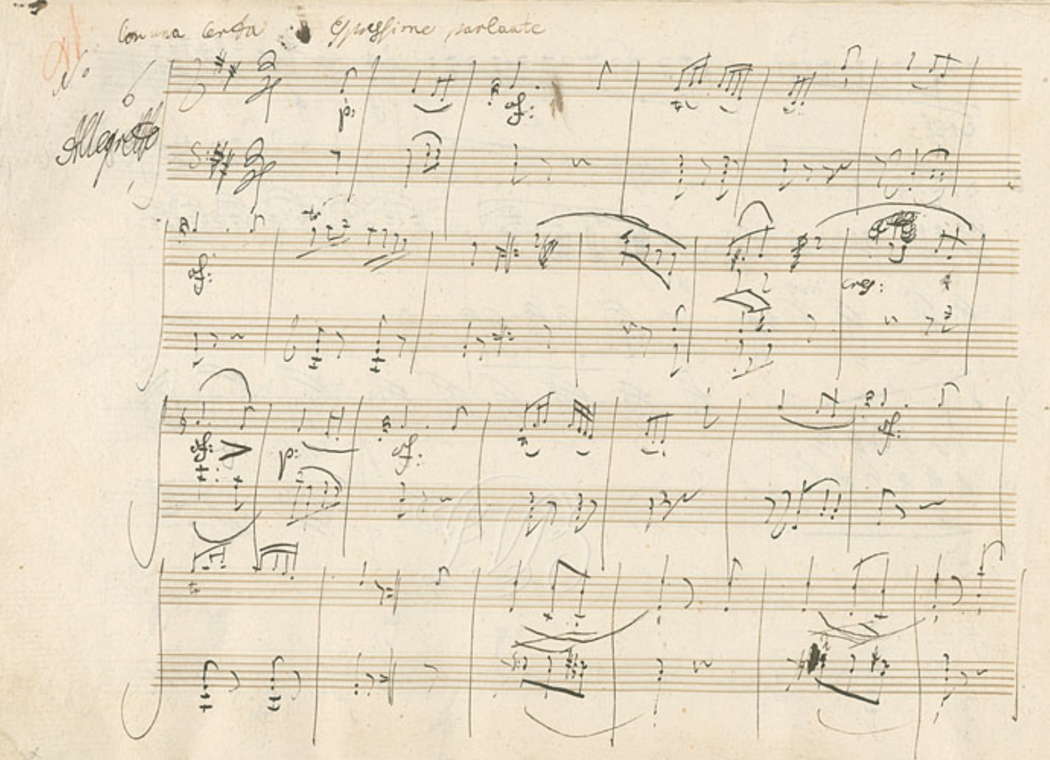

A facsimile of Beethoven's manuscript for the Bagatelle in D, Op 33 No 6 (1801-2)

Since in-person instruction had been suspended, my lessons were being conducted via Facetime on my cellphone, an awkward arrangement at best, even without the issue of a broken key. In desperation I called my tuner to see if he was willing to come to my apartment. We would observe all safety precautions. I would not offer him tea and cookies which had been our usual ritual in the past.

Fully masked, he arrived with the tools of his trade. After forty-five minutes I ventured into the room where the wounded piano still reigned. Bad news. Unless he could order certain parts, the key was irreparable. They did not make parts for this vintage piano any more. However - he raised one finger and with it, my hopes - there was one person in America who specialized in Victorian-era instruments. He would ask if she was willing to come to my apartment to analyze the problem.

Meantime, what to do for light, assuming I planned to continue with my lessons? After a series of deliveries and returns, I found what appeared to be a suitable lamp. Slim, powerful, graceful. There was only one problem: It came complete with no instructions. How did one turn it on or off? No switch was visible. Like a magician I waved my hand over the slim fluorescent bulb, over the flexible stem, over the base, which - though it was the last thing I needed - had a USB port. By pure chance, I waved my hand over an indentation in the base and - Eureka! - there was light! Three degrees of brightness, depending on how I waved my fingers. I swear I was not touching anything, just the air above the base. To turn it off, I just wriggled my fingers from right to left and it went off. Since the fixture was made in China I can only assume it was that country's way of frustrating American commerce. I had to admit it: this was a superior product.

Gloria's new piano lamp

To inaugurate the lamp, which amazingly cast a wide beam over two 8X12 pages despite the short length of the bulb, I decided to return to my daily practicing after a long hiatus. I was struggling with a Beethoven bagatelle in honor of his birthday when I touched the dead D. Dear reader: it was dead no longer. It had been in a coma as a result of its injury but was now fully restored to life. I have no doubt that its recovery was due to my new lamp which, unlike Aladdin's, required no rubbing, but just a mere wave of the hand.

New York, USA

RECENT ARTICLES ABOUT PIANO MUSIC