DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fascinating Recording - John Joubert's string quartets, heard by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

ON FISCHER-DIESKAU'S SCHUBERT

PATRICK MAXWELL investigates the German baritone's legacy

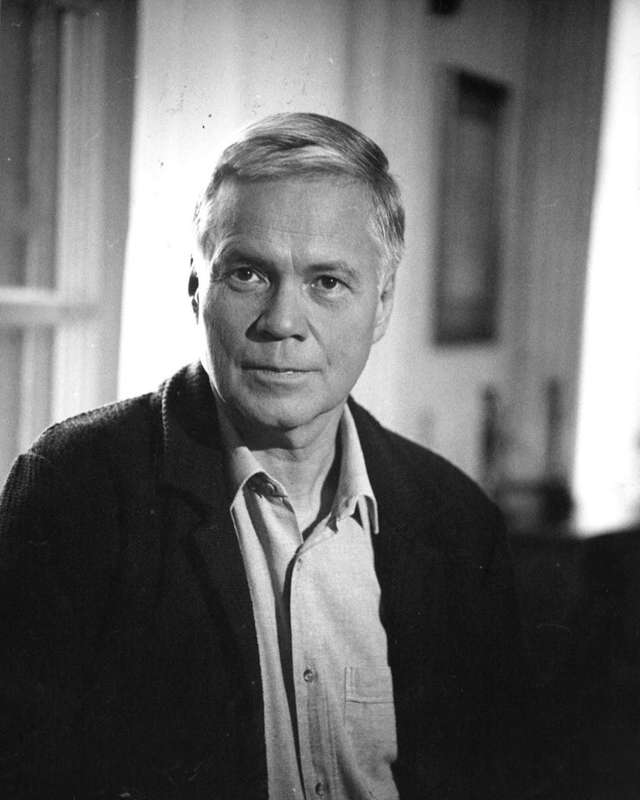

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1925-2012) remains for many who know him a distinctly twentieth-century figure, his voice supposedly reminiscent of a conservative and reliable quality lost to the concert halls and recital platforms he graced for fifty years, and the unending number of recordings which bear his name. The diction, the tone quality, the legato cantabile which is there on every word is like a singing version of chiaroscuro, the sharp contrast of lights and darks, shadows and spurts of colour. It's there in the grinding first notes of Winterreise, the mellow mellifluousness gasping at each breath. Images show him parading the stage, in utter control of his voice and expression, guiding the poor listener through the songs to show them how it's done. Very antiquated, very continental, very formal.

German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1925-2012)

Yet lieder, the art form he transformed and rekindled, is not formal, or especially suited to the authoritative or strict image Fischer-Dieskau's legacy has given to him. There's nothing of a grand old man in the miller boy who wanders around searching for the slightest look from Die Schöne Müllerin herself after whom he lusts. The poetry of Schiller, Heine and Wilhelm Müller which Schubert used so much is constantly besotted by youth or elegising the loss of it.

A circa 1830 engraving of the German poet Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827) by German draftsman, engraver and painter Johann Friedrich Schröter (1770-1836)

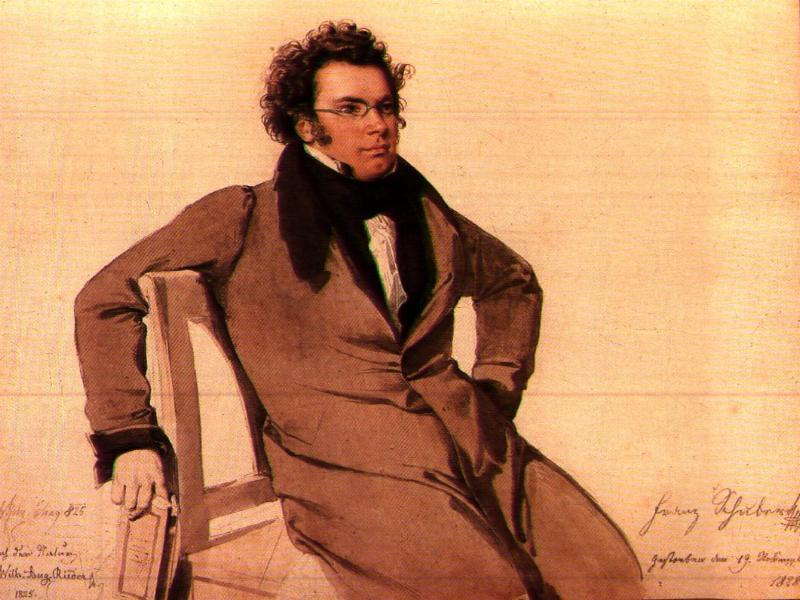

Franz Schubert's genius, as the arch Romantic figure he is known as, was to combine melody, accompaniment and poetry in such a complementary package.

An 1825 watercolour of Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797-1828) by Austrian painter Wilhelm August Rieder (1796-1880)

Fischer-Dieskau's, in a lifetime spent working on these works, was to bring a universal voice to them.

Of course, his fame comes first from that voice. Critics who would spend hours searching for faults in others can mainly only listen and marvel at the beauty of it, and the consistency of that sound over all his works. Today, just to listen in to any of his many versions of Winterreise is to hear the intensity of each rendition. Fischer-Dieskau first performed the piece to a Berlin audience in 1943, when the concert was interrupted by an air raid; the audience all cowered into a cellar before going back hours later to resume the recital. His disabled brother was killed by the Nazis, and he endured a time on the Eastern Front before becoming a prisoner-of-war in 1947. Singing was the thing which maintained him through all this, and it was his singing which maintained so many for the years afterwards.

Both of Schubert's main song cycles are of love-struck, pitiable characters groping over a deserted landscape, fulfilling an easily-mocked cliché, yet they are also of deprivation, ruin and reconciliation. And it was the last three which made Fischer-Dieskau's voice so important; he was the first German musician to become a symbol of the uneasy post-war peace, giving the world outside the new idea of what German culture could be after the barbarism of the years before, and rejuvenating an art form while he was at it. His devotion to Schubert spoke of this, as if he was having to reach back into the trove to show off his country's redeemable qualities. And it's not too much of an overstatement to see his wartime grief evident in his work; every song, bar, note, was given his assiduous attention, his mind evidently wrapped up in the music. Coming from a country turning in its self-inflicted woes, Fischer-Dieskau's voice was the humbled, desperate voice which spoke like the Miller: 'I wanted work ... for the hands, for the heart / fully enough'.

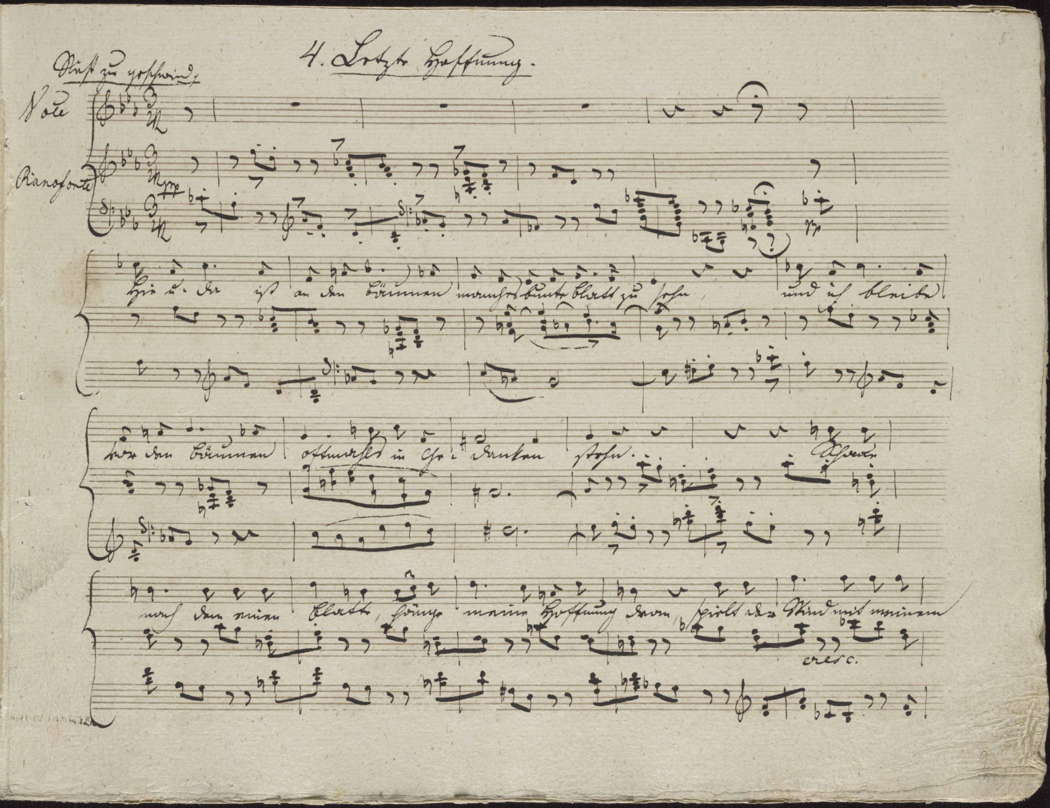

The most memorable musical legacies from after the war, such as the Amadeus Quartet, or the enigmatic genius of Glenn Gould, created an instantly recognisable sound. Fischer-Dieskau's insistence on legato might be controversial, but try finding any other baritone who could get near him in his prime. An innate understanding of the music and the words together, and a greater range whose assuredness was unchallenged for years; no one could reach for the gravity of Bach's 'Mache dich' from the St Matthew Passion and also the heights of Schumann's 'Ich grolle nicht' or Schubert's 'Letzte Hoffnung' with the same pristine clarity and confidence.

The first page of Schubert's manuscript for 'Letzte Hoffnung' from Winterreise

In his own words, it was the 'confrontation' between 'Cantabile and declamatory singing' which must become as much of a combination to fuse all these qualities to make the songs speak for themselves. In his mammoth collection of all Scubert's lieder suitable for his voice, Fischer-Dieskau gives us the fullest, clearest, most all-encompassing exposition of this in over twenty-four hours. The extraordinary 'Eine Leichenphantasie' which opens the first volume is contrasted with the simplicity of 'Die Macht der Liebe' or the tune to 'Die Forelle' which everyone seems to know (not surprising, since Schubert clearly realised he was onto something and had it put into the Trout Quartet). All is treated with an originality and tenderness unheard of in many recordings elsewhere, yet there's an overall theme, a supremely attentive quality, which not only brings us closer to the music and Schubert, but to the emotions of the singer himself. The dedication is all over it, an emotion and eagerness to be the best singer around, to be the man who was the gold standard of lieder, the most powerful singer on the stage. Fischer-Dieskau was a great singer and performer, but it cannot be just an act to give such voices to these pieces; the cathartic element of his Schubert is felt on both sides.

For much of his career, the great renaissance in lieder was due to the great double act of Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore, a man who, if reputations are to be given credence, could not really be labelled as an accompanist. Yet Moore was passionate about his role, and brought his role to the fore with his years of combinations.

English pianist Gerald Moore (1899-1987)

But with Fischer-Dieskau, Moore, who had taken part in the concerts in the National Gallery for respite from the Blitz, had found the counterpart to take both the role of the accompanist and the singer together in a revolutionary way. Their recordings of the two song cycles remain the gateposts from which all attempts at the music must study intensely, and few can since claim to have come particularly near in tone, depth, and scope. To say that these performances can be old-fashioned or dépassé merely casts this music away for being the stale trudge it can seem at first listening, but also dismisses the impact these recordings had, most importantly in bringing lieder to an international audience which had been silently waiting for such music. Each new recording gives a plethora of new interpretations, as all should, yet it can be most fruitful to simply sit back and take it all in - the winter's journey or the miller boy exploring anger, loss, and reflection. For Schubert, so caught up in the tragedy of his own life, yet possessed with his music in the same way as Fischer-Dieskau was in his work, gives us Die Schöne Müllerin, for me easily his finest cycle. It is a journey which makes the listener as captive to the music as the lover is to his girl, a musical narrative which turns on him as the 'lovely' mill, the 'dear stream' betray him and he falls 'down below' to the cool rest' in the penultimate song. This moment, musically simplistic yet all the more cumulative and affecting for that, can only deserve the spell of silence Fischer-Dieskau's voice gives over his audience.

Buckinghamshire, UK

MORE ARTICLES ABOUT VOCAL MUSIC