- Jacques Thibaud

- Verdi: La traviata

- Uruguay

- Johann Krebs

- Johann Strauss the Father

- Antonio Sacchini

- Ilkka Kuusisto

- Justin Connolly: Tesserae C

A TALE OF TWO CENTURIES

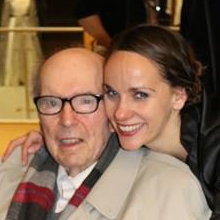

JENNA ORKIN reads Emile Naoumoff's 'Chronicles With Nadia Boulanger'

There exists among us a species of people who are so endowed with natural gifts, not the least of which is an abundance of energy, that they are able to achieve more at an early age than ordinary mortals dream of over the course of their entire lives. What goes against the grain for most of us, demanding the reining in of our natural tendency towards dissipation - steely discipline, in other words - is precisely what drives them. They don't take holidays, not because they're workaholics, but because they feel no need; their work is their deepest joy. They do not envy others because what would they envy them for? The people I'm describing may not be rich or famous but it doesn't matter. What matters to them is seeking whatever their gifts permit them to perceive, whether it be truth or beauty, and having found it, to nurture it, bring it to fruition, finally to express it and share it with the rest of us.

Such a person was the musical pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, teacher of Aaron Copland, Daniel Barenboim and Quincy Jones, among thousands of others, whose insights were sought throughout the last century by composers and performers from Igor Stravinsky to Leonard Bernstein. Such a one, also, is her final protegé, Emile Naoumoff who, at the age of seven, left his native Bulgaria with his parents on the advice of a musically astute family friend, to seek out this woman on the other side of the Iron Curtain, not even sure if she was still alive.

The pilgrimage to the Boulanger residence on the Rue Ballu in Paris left a vivid impression on the young Emile. In a memoir that is available in its entirety on his website, he writes that unsure of how to find the place, his parents asked a woman they encountered on the street,

only realiz[ing] after they asked the question that she was a prostitute, perhaps forty or fifty years old, distinguished enough, if a little odd, with a rather pronounced nose and an air of Toulouse-Lautrec in her ancestry. My father told me that she and the other women of similar presentation in the area were guardians, like policewomen (they soon seemed to me to be a logical extension of the circles of demoiselles surrounding me in my daily activities...) [Boulanger relied on a coterie of female assistants, several unpaid and some, such as the Solfège, clef reading and rhythm teacher Annette Dieudonné, themselves supremely gifted.]

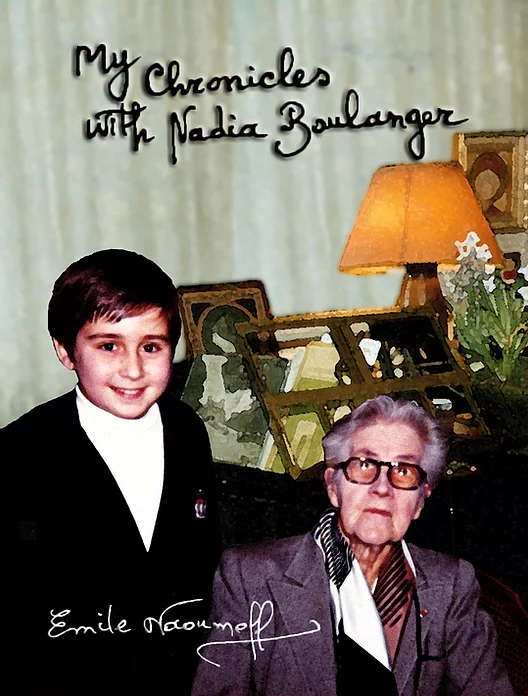

Emile Naoumoff: My Chronicles with Nadia Boulanger

Having been directed by this neighborhood 'guardian' to the correct building, the Naoumoffs made their way to Boulanger's apartment, via

the tiny elevator, as is often the case in buildings where such a luxury was never foreseen, with its mesh-wire door closing like a noisy guillotine, and its arrival at mid-floor (the same mid-floor that Nadia Boulanger's cardiologist would carry her across after her last stay at Fontainebleau in 1979, an effort that contributed to his own collapse and death later that day – news that no one dared to tell her).

'Mlle Boulanger' succeeded in convincing Emile's parents

that she was where I was supposed to be. This was not too difficult a task given her moral authority – despite the fact that she was not an institution or conservatory with the power to bestow a diploma, but an individual (admittedly of worldwide repute) liable to die the following month. [Boulanger was eighty-one.]

What followed was an education that might be likened to the musical equivalent of that bestowed or, more accurately, forced, on John Stuart Mill, with the notable difference being that in Naoumoff's case, the recipient was willing. In addition to a normal academic class load at the Hattemer School, which he found far more onerous than any musical assignment, no matter how tortuous, he studied three afternoons a week as well as Saturday morning with Boulanger and her 'right hand man', Annette Dieudonné; sometimes, on evenings when there was a soirée with the musical and artistic intelligentsia of the day, not arriving home by cab until 1 AM. Then it was up at five the next morning to prepare with his mother for that day's classes at Hattemer.

Nadia Boulanger with Emile Naoumoff, aged ten

The chronicle of Naoumoff's unique upbringing in those years is fascinating for the general reader since he brings to his literary task the same enthusiasm and generosity of spirit that he devoted to the study of music. The book is shot through with breathtaking asides that imbue it with historical perspective: One of Mademoiselle's many friends among the aristocracy of Europe (some of whom were accomplished students; the preface to the memoir is by Irène, Princess of Greece) had been the Princesse de Polignac, whose mother had served as Bartholdi's model for the Statue of Liberty. De Polignac herself had been the actual princess to whom Ravel dedicated his Pavane For a Dead Princess. Debussy and Rachmaninov stride these pages not only as musical giants but also as noisome human beings. Boulanger was apparently affronted by Debussy's scorn for the Prix de Rome which had been won by her younger sister and student, Lili, before her death at twenty-four of tuberculosis, and which Nadia herself ardently sought. Rachmaninov had refused the dying request of Boulanger's beloved colleague Raoul Pugno that he replace Pugno at a concert with Boulanger. Boulanger seems not to have been alone in the belief that Rachmaninov's reason sprang from misogyny although Naoumoff also conjectures that he may have wanted to avoid contagion from the virus that had brought about the request in the first place. With more certainty, Camille Saint-Saëns is revealed to have played a key role in depriving Boulanger of the much coveted Prix de Rome on misogynistic grounds.

But it is as a record of Boulanger's course of training that this book may be of greatest interest to those musicians who happen upon it. Anyone who undertook such a regimen would indeed become 'the compleat musician'. Thus was Naoumoff, a composer whose piano concerto, written when he was ten, was conducted by Yehudi Menuhin, able also to embark on a career as a conductor, concert pianist, transcriber, accompanist who could transpose at sight and professor at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

Boulanger herself embodied her own ideals:

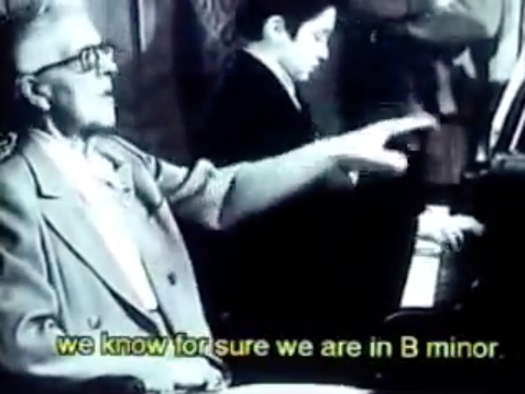

She would ... sit to my right, her eyes closed, improvising fugues over the top of my part, fingers moving as by a mechanical enchantment, all while speaking to me.

Like all self-respecting organists, Nadia Boulanger – who apparently often sat in for Fauré at the Madeleine Church in Paris, even when underage (if anonymously, because it was prohibited) – could lavishly improvise, and even though her strength had diminished significantly by the time I met her, she still had a sort of internal drive or inner tension, like a string pulled almost to the point of breaking.

Of course, in the pursuit of the most exalted musical goals, certain other aspects of Naoumoff's education fell by the wayside. True to the cliché about child prodigies, he didn't learn how to tie his shoelaces until he was eighteen, his mother accommodating this lapse by simply buying him moccasins instead.

Naoumoff's memoir was copyrighted in 2015. I believe I originally read a portion of it years ago before it had been completely translated. But a recent Zoom reunion of the Fontainebleau class of 1978, with Emile very much present, prompted my renewed interest. It's an invaluable book, offering a glimpse into a way of thinking that runs counter to many of the belief systems about education that are prevalent today. In fact, it is a monument to the entire musical culture not only of the twentieth century but also of the nineteenth. And to appreciate and preserve that culture is essential to our understanding if we hope to advance beyond it.

New York City, USA