- Paul Zukofsky

- Caroline Charrière

- Max

- Aotearoa

- Steven Isserlis

- Regensburg

- Frances Forbes-Carbines

- Adolf Mišek

It Pays to be Brave

George Frideric Handel's 'Rinaldo' in Florence, reviewed by GIUSEPPE PENNISI

Alexander Periera has the reputation of being brave for his management and programming at the Zurich Opera House, at the Salzburg Festival and at La Scala. Now he is the superintendent of the Florence Opera House - Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. This is the first theater that has opened its post-pandemic seasons on 7 September. The first in Italy, in Europe and, I believe, in the Western World. I was at the 14 September 2020 performance.

The opening was a revival of a production of Handel's Rinaldo which his predecessor at the helm of the Florence Opera House, Cristian Chiarot, had programmed for last March, when the lockdown started. The production, originally presented in 1985, has travelled to as many as twenty-five major opera houses in Europe and in Asia with minor adjustments to fit individual stages and the availability of singers. Thus, it has well amortized its production costs, at least its elaborate sets, costumes and stage machinery. In Europe, between 1985 and 2005, Rinaldo has been seen in Milan, Paris, Lisbon, Madrid, Geneva, Venice and several opera houses of smaller cities. It was a major hit even in Seoul where it was played in a huge oversized house even though the production had been originally conceived for the elegant but not very large Teatro Romolo Valli of Reggio Emilia. I saw it at La Scala in 2005 and in Ravenna in 2012.

This revival uses the impressive stage sets and costumes of 1985 but it differs from the Ravenna performances in three important aspects. For the first time (in thirty-five years), the role of the protagonist is played not by a mezzo but by a countertenor. The large stage of Florence Opera House as well as the advanced equipment - especially the lighting - fits perfectly with the grandiose set machinery. The Maggio Musicale orchestra is not a specialized baroque orchestra but, under the experienced and clever direction of Federico Maria Sardelli, did an exceptional job, especially the flutes and horns.

Federico Maria Sardelli conducting Handel's Rinaldo in Florence. Photo © 2020 Michele Monasta

Rinaldo has a special place in Handel's work: it is his first Italian opera especially composed for the London stage, not an adaptation of previous works. The combination of an elaborate series of bewildering scenic effects with a strong cast and music of great passion, brilliance and sensuality made it a sensation for the 1710-1711 London season, when the opera had as many as forty-seven performances at the Queen's Theatre. The opera's fame was such that, in spite of the poor means of communication of the time, Handel prepared a new version (with 'buffo' characters and arias) for performances at the Royal Theatre in Naples in 1718. A third, expanded and longer version was set for London's King's Theatre in 1731. The Florence production is based on the original 1711-12 version. It lasts about three hours with an intermission, whilst the 1731 version would last some five hours. It is well known that in the eighteenth century, people dined, drank, played cards and even dated during a lengthy opera evening, just to get musically excited when their favorite singers had their acrobatic musical numbers. Today, the pace of life is faster and people go to the opera to follow the performance.

Baroque operas are not often staged in Italy, both for their vocal and scenic requirements and for the specific Italian national musical tradition. However, they do attract a younger audience than melodrama and verismo do, probably for their abstract unrealistic nature as well as for the emphasis on music, singing and rather overt sensuality. Rinaldo is broadly based on Torquato Tasso's poem Gerusalemme Liberata. However, the plot - tormented love affairs and battles during the first Crusade - is no more than a pretext for 'very special' theatrical effects and singing. Also, there is no psychological development of the main characters - both Christians and Muslims. It is just pure music and pure singing in an ever changing scenery designed to stupefy the audience.

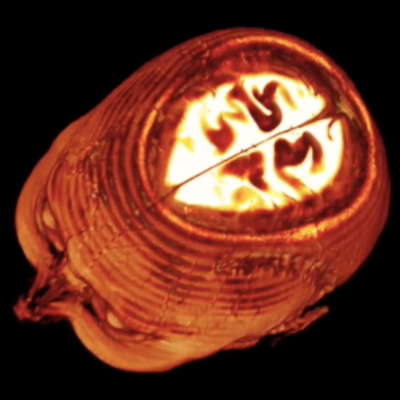

Pier Luigi Pizzi solved the scenic demands, eg open stage transformation, forests, castles and battles around Jerusalem's wall, by using sophisticated and, at the same time, simple machinery: the basic tenement of Japanese Kabuki with elaborate props handled by stage-hands. The photos provide an idea of the sensational effects, especially in the second act where the front scene depicts the sea and in the latter part of the stage Armida's castle of pleasures and sins becomes the grotto of a devout Christian magician. This is done with constructed stage elements, not with computerized projections.

Leonardo Cortellazzi as Goffredo and Willam Corrò as Mago Cristiano in Act III of Handel's Rinaldo in Florence. Photo © 2020 Michele Monasta

Rinaldo's stage direction, however, calls for young singers who can handle acrobatic acting and vocalizing. A few words on the orchestra: slender and essential with very good winds. This was wanting in the 2005 La Scala performances where a large orchestra and modern instruments were utilized. Sardelli and his colleagues gave a sensual rendering of the score, almost caressing the audience and always supporting the singers' difficult task.

In the 1711 and 1731 editions, the title role was conceived for a castrato - Nicolino and Senesino respectively. In the current production it is sung by countertenor Raffaele Pé, one of the most appreciated in Europe. He is very manly and sensual in his scenes with his lovers, Almirena and Armida, his vocal range extends to E5, and he has a perfect register. He also sings and fences with the Saracens while riding a horse. His is a taxing role with as many as eight ABA arias. From his entry aria 'Ogn'indugio d'un amante', he acquitted himself quite well. He received open stage applause after 'Venti, turbine, prestate' and open stage ovations after 'Or la tromba in cuor festante'.

The Chief of Staff of the crusaders' army is the tenor Leonardo Cortellazzi. His arias give him a lot of vocalizing and some hard legato, but his role excels in the duets. In the men's group, the writing for his opponent, the Saracen Chief of Staff and King of Jerusalem, Argante, sung by baritone Andrea Patucelli, is quite remarkable. He is a memorable character right from his cavatina or starting aria 'Sibillar gli angui d'Aletto' to his duet with Armida and final ensemble with the rest of the company, after his rather unbelievable conversion to Christianity - a price that Handel and his librettists - Aaron Hill and Giacomo Rossi - had to pay to London politics.

However, Rinaldo is a women's opera. The dominant character is Armida (Carmela Remigio), first of a line of formidable Handel sorceresses - such as Alcina. She gives an immediate sense of fiery sexual passion with her cavatina 'Furie Terribili'. Her sensuality reappears in her great aria 'Ah! Crudel il pianto mio', introduced by solos of oboe and bassoon; she had a long open stage applause. On the other hand, Almirena, Rinaldo's fiancée, sung by Francesca Aspromonte, is sweet and tender. She received ovations after the aria 'Lascia che io pianga', borrowed by Handel from his Rome oratorio Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno. She enthralled the audience in the charming birdsong aria 'Augeletti' with flute accompaniment.

Leonardi Cortellazzi as Goffredo, Francesca Aspromonte as Almirena and Raffaele Pé as Rinaldo in Act III of Handel's Rinaldo in Florence. Photo © 2020 Michele Monasta

At the curtain close, there were nearly fifteen minutes of applause and ovations for Raffaele Pé. This augurs well for Florence, as well as for opera houses around the world.

Copyright © 16 September 2020

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL

FURTHER LIVE CONCERT AND OPERA REVIEWS