FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

FEEDBACK: She said WHAT? Read what people think about our Classical Music Daily features, and have your say!

Especially Enjoyable Hard Work

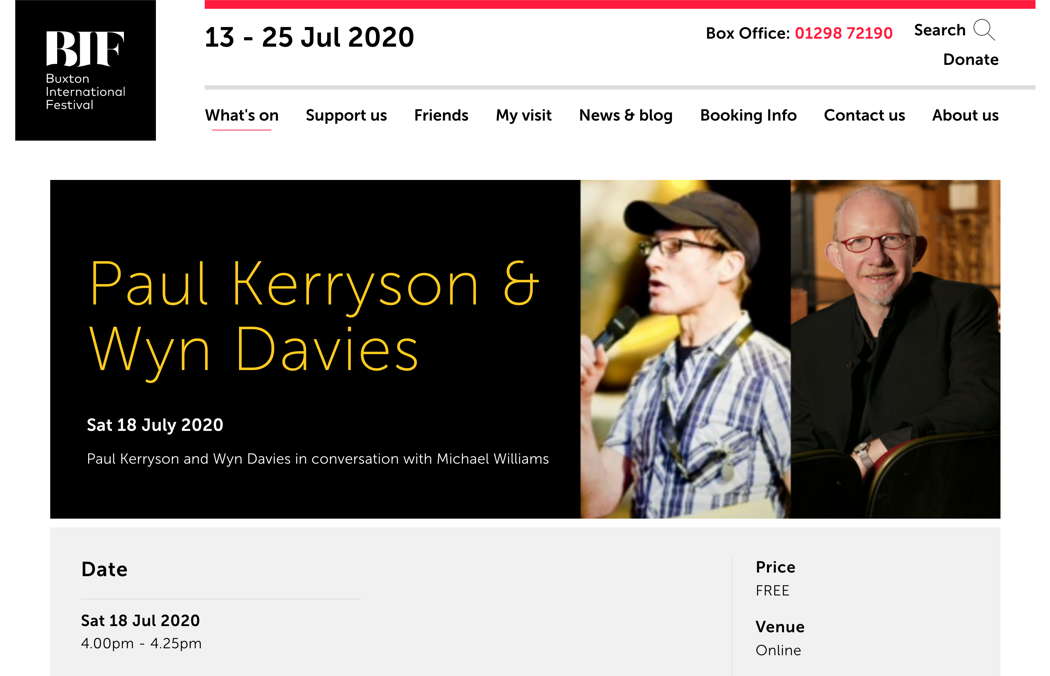

Paul Kerryson and Wyn Davies explore the work of Stephen Sondheim and 'A Little Night Music', in conversation with Michael Williams, as part of the Buxton International Festival Digital 2020 Season, reviewed by MIKE WHEELER

Buxton Opera House and Buxton International Festival were due to stage their first co-production (and the Festival's first-ever musical) this summer, with Sondheim's A Little Night Music, now held over until next year. Festival Chief Executive Michael Williams discusses the show with the director, Paul Kerryson, the Opera House's Chief Executive, and the conductor Wyn Davies, who is well-known to Buxton audiences.

Why choose this particular show? asks Williams. For Kerryson, A Little Night Music is 'full of fun and wit ... intellectually satisfying, a wonderfully breezy night out'. Williams asks Davies to enlarge on a previous statement that it was one of his 'most favourite' musicals. Davies replies that there are no weak links, the book is a first-class play in its own right, and that Sondheim is, simply, 'the top composer of American music theatre'.

Online publicity for the Buxton Festival film 'Paul Kerryson and Wyn Davies in conversation with Michael Williams'

And yet, comments Williams, sometimes Sondheim gets what he calls 'a bad rub' in the press for his more adventurous works, and asserts the strong narrative drive of shows like A Little Night Music and Sweeney Todd - 'he's at his best when he tells a damned good story'. He suggests to Kerryson that putting on a Sondheim show requires 'a lot of work, a lot of thinking'. Kerryson agrees. Bringing the right creative team and cast together, for staging Sondheim, or anyone else, is a lot of hard work. But with A Little Night Music 'it's especially enjoyable hard work'. With the right cast and the right creative team, it becomes less hard. Directing the show 'will be a joy'.

Williams' brief summary of the plot focuses on the mismatched lovers, the show's themes and mood often drawing on A Midsummer Night's Dream. He then comments on the waltz rhythms that permeate the entire score. For Davies, the waltz is nostalgic, with its echoes of Viennese operetta. He points out the prominence the opening lyric gives to the word 'remember', and that the waltz perfectly expresses that. Sondheim, he says, 'doesn't do things by halves. Practically every bar, every number, is in threes.'

Williams suggests that Sondheim's complex metres and pitch [key?] changes are challenging for singers. Is that why this work is often tackled by opera companies? 'Sondheim's music is never easy', replies Davies. 'There are always quirky things about it, difficult rhythms which must be accurate, or they don't make any sense.' And the tunes often don't do what you think they will.

Williams then touches on the show's themes of youth and age, and their different views of love and life. Madame Armfeldt teaches her granddaughter about the midsummer night smiling three times, 'at the young, who know nothing, at fools, who know too little, and the old, who know too much'. For Kerryson, the reason people adore this musical is because they can identify with the different generations, with the grandmother and granddaughter observing 'all the mayhem caused by the intermediate generation' to which most of the characters belong. For Davies, Sondheim's ability to pinpoint what the different generations are thinking and feeling is crucial, expressed with a great deal of clarity. So we see the younger characters who 'want to get on with the here and now', the middle generation trying to correct past mistakes, and Madame Armfeldt, 'the wise old owl, sitting back and commenting on it all'.

Is Sondheim a theatre-lover's choice? asks Williams. Is he so theatrical that it puts people off? He remembers seeing Into The Woods with Bernadette Peters [so presumably the US first production], and was blown away. But the reviews trashed it. Does conventional wisdom say that Sondheim is not immediately appreciated? Kerryson recalls his time at his own theatre [Leicester Haymarket] when he had the luxury of putting on a Sondheim show once a year for about eleven years, during which time 'audiences grew and grew and grew'. Sondheim is 'much more accepted, more loved and admired than when I started in the 90s'. Prompted by Williams, he recalls his production of Merrily We Roll Along, which Sondheim and book-writer George Furth came over from the States to see. Was it a stressful experience?. 'A pleasurable stress', Kerryson replies, describing the 'privilege of having this composer in the rehearsal room for four weeks'. As the first staging of the show's revised version, it was very important to Sondheim. There were nerves among the cast, and tension between director and writer at first. But on one occasion Sondheim asked for a change at a particular point. His suggestion was tried out, and his reaction was: 'no, I've made a mistake here; it was much better how you were originally doing it.' That broke the ice, and taught Kerryson there was no reason to fear having the writer in the room.

How does that compare with Davies' experience of conducting contemporary operas? 'Most of the time', he replies, 'composers are just deliriously grateful to have the thing done at all.' Some composers are better than others at writing down accurately what they want. There is some leeway with Sondheim, 'but the rhythm is usually very precise'. He jokes that Kerryson has just given him the green light to intervene with suggestions, 'and he is obviously going to do what I say'.

A screenshot from the Buxton Festival film 'Paul Kerryson and Wyn Davies in conversation with Michael Williams'

Asked to comment on the designs for his production, Kerryson makes an intriguing comparison. The environment and the action of A Little Night Music need to be very flowing, even Ibsenesque. Ibsen can be extremely funny, and productions of Ibsen that bring out that quality 'are always the best'. So the design has to make the characters look as if they are 'floating on thin ice', and this has prompted a more abstract visual style. Davies adds that what seem to be operetta characters at the start later turn into something more serious, more Ibsenesque. He quotes the show's original producer and director Hal Prince's description of it as 'whipped cream with knives', and any production needs to bring out that edge.

Casting the Buxton production was well advanced, says Williams [including Janie Dee - Phyllis in the first run of the National Theatre's recent production of Sondheim's Follies - as Desirée Armfeldt], and Kerryson would be delighted to get that cast back for the deferred staging next year. With so many actors and musicians currently out of work, 'they are just waiting for someone like us to give them a platform for their talent again'.

Copyright © 23 July 2020

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: BUXTON FESTIVAL