VIDEO INTERVIEW: Ona Jarmalavičiūtė talks to American choral conductor Donald Nally, director of The Crossing, in this fascinating, illustrated, one hour programme.

VIDEO INTERVIEW: Ona Jarmalavičiūtė talks to American choral conductor Donald Nally, director of The Crossing, in this fascinating, illustrated, one hour programme.

PROVOCATIVE THOUGHTS:

The late Patric Standford may have written these short pieces deliberately to provoke our feedback. If so, his success is reflected in the rich range of readers' comments appearing at the foot of most of the pages.

- Venice

- Louise-Angélique Bertin

- John Eliot Gardiner

- Lockerbie

- BBC Russia

- Schleedorf

- Rosie Aldridge

- Tania León: Ajiaco

BEETHOVEN 250

In this year of celebration,

GIUSEPPE PENNISI muses on

Ludwig van Beethoven's modernity

The 250th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven's birth is the event to characterize the 2020 musical year. The composer was born between 16 and 17 December 1770 - music historians do not agree on the exact date and at that time the civil status records were rather lacking - in Bonn, where his grandfather (named Ludwig also) had arrived decades earlier from Flanders where the family practiced small farming. The prefix 'van' - often crippled in a noble 'von' - indicates the Flemish/Dutch origin of the family. He died on 26 March 1827.

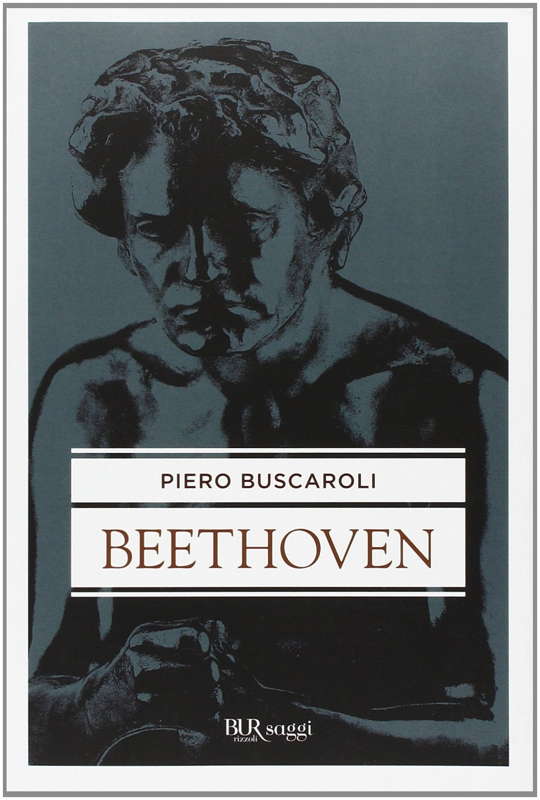

All over the world, major musical institutions have – as is right – programs to celebrate a giant of European composition between the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century - a true colossus at the turn of two centuries. We will hear his symphonies, his vast piano production, his chamber music, and his unique, and so troubled, opera Fidelio which required three different drafts. New studies and essays will enrich the already rich production on the composer: in his 1080-page volume on Beethoven in 2004, Italian musicologist Piero Buscaroli (1930-2016) recalls having used as many as 120 books as 'main sources' for his research – as well as an immense amount of texts as 'secondary sources'.

Piero Buscaroli: Beethoven

© 2010 Saggi, ISBN 978-8817039123

I wish that Beethoven's celebrations will not become a fair, as they have been, in the recent past, for Mozart, Verdi and Wagner in their anniversaries. I hope that listeners - the programs have already been defined for years - will follow a thread to give an accomplished sense to the various events. In my opinion, the thread that should link listening to Beethoven's works is the modernity, not of all, but of many titles in his catalogue. It is a line not always followed or understood. It is seen in a reductive way in which Beethoven is considered as a precursor - also of a couple of decades - of German Romanticism. His modernity is much more up-to-date.

Banner for Chicago Symphony Orchestra's Beethoven 250 celebrations

Think of the last quartets. In 2014, the then artistic director of the Academy of France in Rome at Villa Medici had the happy idea of juxtaposing, in a series of concerts in the Grand Salon, the last quartets of van Beethoven with those of a number of contemporary musicians then still alive, including Pierre Boulez: to the listeners, the assonances appeared numerous. One cannot think that one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century had, in some way, 'plagiarized' his predecessor; despite a very different context of musical culture, Beethoven had preceded Boulez.

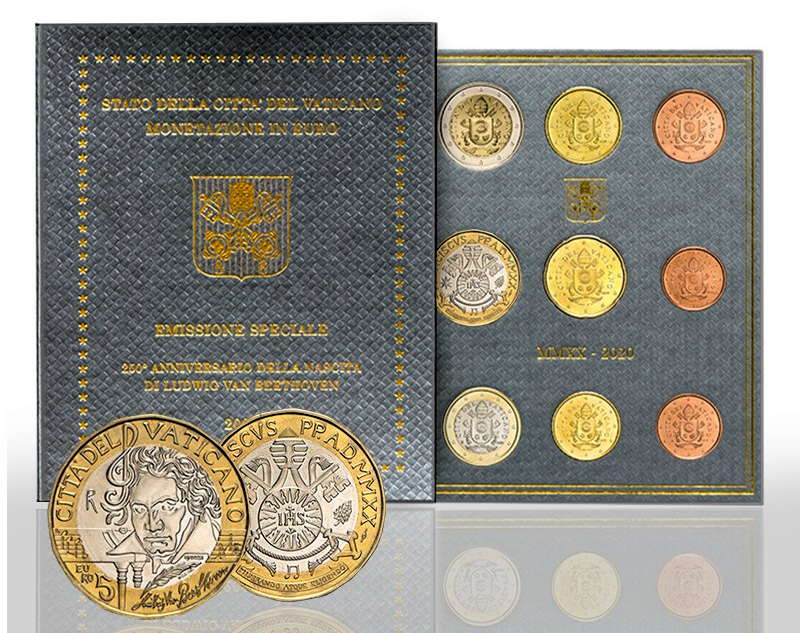

The Vatican Philatelic and Numismatic Office's nine-piece coin set marking this year's 250th anniversary of Beethoven's birth

Think of overtures such as Die Weihe des Hauses, König Stephan, Egmont, Coriolan and especially Leonore No 3, originally designed for one of the versions of Fidelio and today often performed between the first and second scene of the second act of the opera. In the last years of the nineteenth century and especially in the early part of the twentieth century, they would have been tone or symphonic poems such as those by Richard Strauss and by Ottorino Respighi, a style not yet born when Beethoven lived and composed.

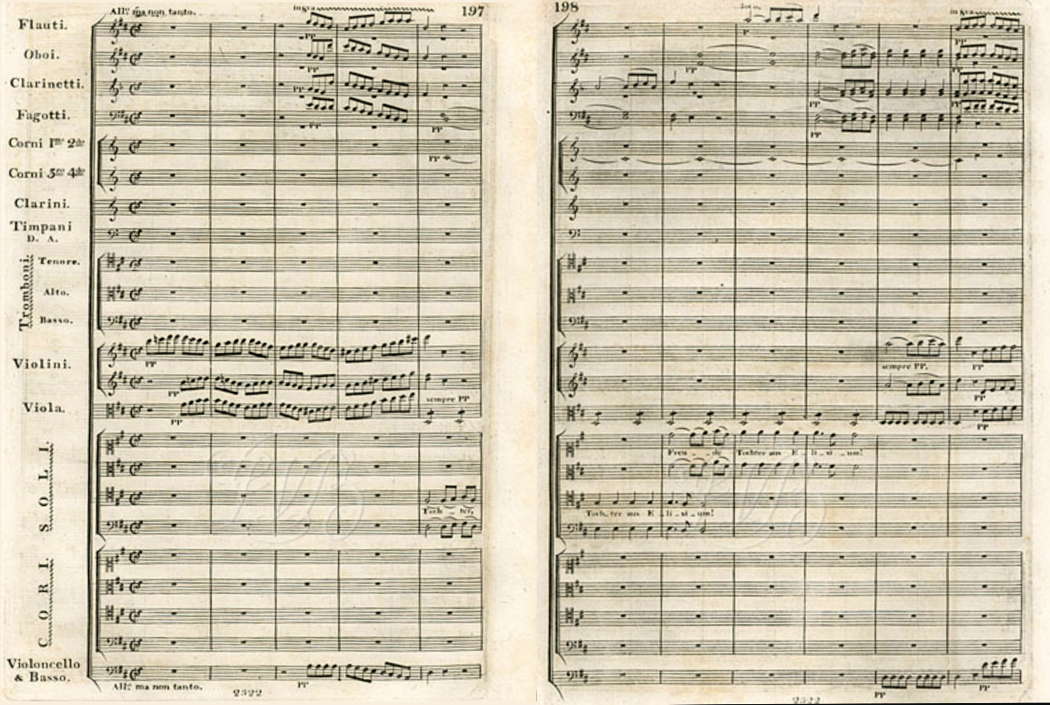

Another example is the Ninth Symphony – subtitled allemande by the composer who, although he lived for decades in the capital of the Austrian Empire, considered himself deeply German and did not want to be confused with the 'School of Vienna'. To the symphonic style as formalized by Franz Joseph Haydn in four movements, Beethoven added the human voice, pre-chasing Gustav Mahler.

The first two pages of the first edition of the choral finale of Beethoven's Symhphony No 9 in D minor, Op 125

Finally, we come to his only work for the theatre: Fidelio. There is no novelty in form: it is a Singspiel in which as in the French opéra comique (which could also have tragic content), dialogue alternates with musical numbers. There is nothing new in the big arias, to a large extent of Italian derivation. There is nothing new in the intensity and originality of the declaimed vowel. Yet, as Richard Wagner wrote, it is the first modern music drama, at least eight decades ahead of the Italian opera drama.

Rome, Italy

FURTHER INFORMATION: LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

FURTHER INFORMATION: PIERO BUSCAROLI