- New Grove

- Helicon Classics

- Nicholas Kok

- Johannes Pullois

- The Magic Flute

- Naji Hakim

- Worcester Festival Choral Society

- David Ireland

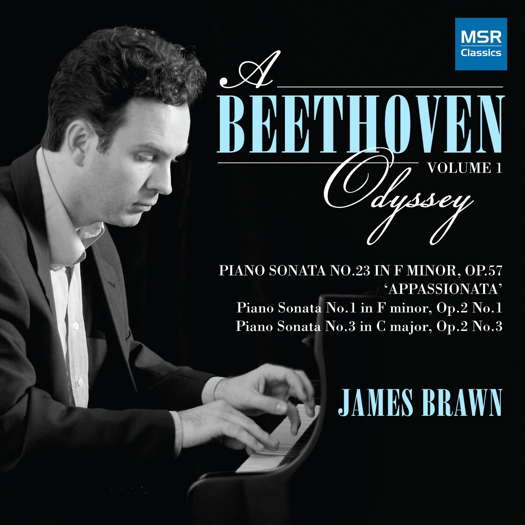

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterfully Controlled - James Brawn's Beethoven Odyssey impresses Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterfully Controlled - James Brawn's Beethoven Odyssey impresses Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Improvisation in the classical world and beyond, including contributions from David Arditti, James Lewitzke, James Ross and Steve Vasta.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Improvisation in the classical world and beyond, including contributions from David Arditti, James Lewitzke, James Ross and Steve Vasta.

Familiar Pieces Heard Afresh

MIKE WHEELER has some thoughtful comments

on a performance by Tasmin Little, Duncan Riddell,

Thierry Fischer and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

No handshakes between conductor, soloist and leader on this occasion - amid proliferating public health advice, Thierry Fischer, Tasmin Little and Duncan Riddell, respectively, greeted each other with fist bumps. It brought smiles to what could have been a more subdued occasion in the circumstances - Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, UK, 11 March 2020.

Not that there was any danger of that once Little, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Fischer launched into their engaging account of Mozart's Violin Concerto No 4. Reducing the number of orchestral strings helped to produce a rich but not over-upholstered sound. Little's first entry was pert and fresh-sounding, and she engaged in some playful backchat with the orchestral violins. A poised reading of the second movement saw her throwing off some charming approximations of birdsong in the higher-lying passages and bringing a meditative calm to the cadenza. In the finale Mozart juggles gavotte-like courtly manners with something more skittish. The mood-changes were handled adroitly, Little was disarmingly open-hearted in her solo rustic episode, and the pay-off was a study in collective elegance.

Tasmin Little

Before the Mozart came the Overture to Borodin's Prince Igor, as pieced together by Glazunov. The sombre introduction had the sense of a weighty tale unfolding, but a not inappropriate degree of brashness kicked in once the quicker music started, and the latter galloping music had plenty of spring.

Throughout, the brass was weighty but not overwhelming, and that was a feature, too, of the sound in Brahms' Symphony No 1 after the interval. Was the brass section using narrow-bore instruments, I wonder? After a stern introduction, the main part of the first movement was powered by a defiant streak verging on rage, but all contained within the framework of Brahms' basically classical aesthetic. The second movement was particularly notable for John Roberts' poignant oboe solo, and the provisional benediction of Duncan Riddell's solo contribution towards the end. There was a delicate balance held between the robust and the more fragile moments of the third movement, with clarinettist Fiona Cross leading the way.

The pizzicato cellos and basses at the start of the finale began from barely audible, with the subsequent build-up steady and not over-excited. Someone once told me they thought the solo horn-call was 'sad'. In Rodrigo Serranto's playing I could hear just what they meant. The big tune went at a steadier pace than I've often heard - but what can you do with Brahms' contradictory tempo marking? There was plenty of excitement as we headed towards the coda, the transition to which was handled in a particularly convincing way. As I listened it occurred to me that Brahms seemed not entirely convinced by his triumphant ending, but wished he was.

Johannes Brahms in about 1872

Fanciful perhaps, but as I've commented before, the performances that make you hear familiar pieces afresh are the ones you remember.

Copyright © 21 March 2020

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

FURTHER INFORMATION: ALEXANDER BORODIN

FURTHER INFORMATION: ALEXANDER GLAZUNOV

FURTHER INFORMATION: JOHANNES BRAHMS