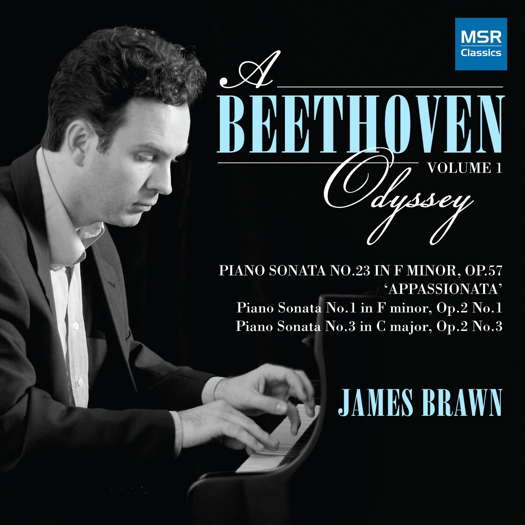

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterfully Controlled - James Brawn's Beethoven Odyssey impresses Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterfully Controlled - James Brawn's Beethoven Odyssey impresses Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

Darmstadt is Dead

A performance of 'Hyperion' in Rome

celebrates Bruno Maderna's centenary,

and GIUSEPPE PENNISI is in the audience

For the centenary of Bruno Maderna's birth, the Istituzione Universitaria dei Concerti (IUC) has proposed a performance of one of his two works designed for the stage, Hyperion. (The other is Satyricon.) A characteristic of these works, and others by the Venetian composer, was to be 'open works' of musica aleatoria (random music) that could take different forms at each performance, eliminating or adding songs, or musical numbers, and changing, therefore, structure, thus creating a new work each time.

The first version of Hyperion, called 'lyrics in the form of a performance', was the result of Maderna's collaboration with director Virginio Puecher, who had given stage form to a set of musical materials already composed independently by the Venetian musician, adapting some of the excerpts of Hyperion, a novel by the German proto-romantic writer Friedrich Hölderlin. The work was staged at the Teatro La Fenice during the 1964 Venice Festival of contemporary music. Maderna continued to work on it, personally preparing two more compositions for the stage - Brussels and Bologna, both in 1968 - as well as four concert versions and two suites - Berlin 1969 and Vienna 1970. There have been many other versions, even without the direct intervention of the author. In short, this was a work in progress that between additions and cuts changed with each execution in a radical way. A concept, in many respects, characteristic of the Darmstadt music school, of which Maderna was a member.

The suite for voice, flute, oboe, choir, orchestra and recorded orchestra presented by the IUC corresponds almost entirely to that performed at the Academy of Santa Cecilia in 1980, nine years after the composer's death; the initial aria for soprano was replaced by an orchestral Introduction from Dimension III, a 1963 composition with a flute cadenza. In the 1980 edition, the voice of the actor Carmelo Bene, who then had great success as a concert performer, for example in Manfred by Schumann, presented at La Scala and Bologna, or the show-concert Majakovsky seen in Rome and at the Umbria Sagra Musicale in Perugia. Carmelo Bene himself made a translation of Hölderlin's text. In this 1980 version, if I remember correctly, the actor's voice took on a greater role than in the previous ones, also because of the personality, and notoriety, of Carmelo Bene.

In 1980, the National Academy of Santa Cecilia Symphony Orchestra was directed by Marcello Panni, who was also on the podium for the IUC's performance this month.

Bene's voice was recorded by RAI for a commercial recording that was never made. The recording was used for the IUC concert. On 4 February 2020, the Orchestra Sinfonica Abruzzese was in the pit. Ready-Made Ensemble led by Giuliano Mazzini was the chorus, and Ensemble Ars Ludi provided the percussion.

Members of Ready-Made Ensemble and Ensemble Ars Ludi performing in Bruno Maderna's Hyperion in Rome on 4 February 2020. Photo © 2020 Claudio Rampini

The two soloists were Gianni Trovalusci (flute) and Christian Schmitt (oboe).

Christian Schmitt playing in Bruno Maderna's Hyperion in Rome on 4 February 2020. Photo © 2020 Claudio Rampini

I have no memory of performances of Hyperion's over the last forty years, that is, after those at the Academy of Santa Cecilia, while I do remember productions of Satyricon, an ironic and very funny work, at MacerataOpera and at the Festival of Two Worlds of Spoleto in the early years of this century. While Hyperion is closely linked to what can be called the Darmstadt School, from the city, near Frankfurt, home to experimental music, Satyricon is a satire in music, with chansonnier elements, to which Peter Eötvös' works can be related, eg Le Balcon. This small example suggests that Hyperion does not seem to have had a following, while Satyricon has - in addition to Le Balcon, I can mention some biting American and German musical satires of the last thirty years.

This raises questions about the situation of the work of those Italian composers who, in the second half of the twentieth century, were attracted to Darmstadt and followed it: in addition to Bruno Maderna, there were Franco Donadoni, Aldo Clementi and Francesco Pennisi. Pierre Boulez, who was one of Darmstadt's animators, titled a 1951 article Schönberg est mort to decree the end of serialism. Today it can be said that Darmstadt is dead, and indeed has been for decades, to indicate the end of an experimentalism that had few followers and disappeared from the concert halls.

Back to Hyperion and its 4 February 2020 revival (for one evening only). The concert hall was full in every order of places; in the audience were several youngsters interested in getting to know Maderna, who today is very seldom present in the programs of the concert seasons. The audience greeted the concert with warm applause, sometimes on the border with ovations.

A scene from the performance of Bruno Maderna's Hyperion in Rome on 4 February 2020. Photo © 2020 Claudio Rampini

For the IUC it was undoubtedly a huge production effort because the concert requires about eighty musicians. Probably due to an inaccurate recording in 1980 and too high a volume, Carmelo Bene's voice covered the musicians a little, at least for those, like me, who were in the first rows of the hall. This almost gave the impression that the concert was aimed more at remembering the actor (who, I must admit, was never among my favourite performers) than the composer. Bene's voice somewhat blurred the elegant calligraphic writing of the score.

Marcello Panni conducted the large ensemble with delicacy, almost with the sweetness that befits a unique commemoration, that is, without replicas. For him, too, it was a re-enactment of an important moment forty years ago.

Marcello Panni conducting Bruno Maderna's Hyperion in Rome on 4 February 2020. Photo © 2020 Claudio Rampini

It was felt by the gentle touch of the first episode - Introduction and message - in which the orchestra dialogues, as well as with Carmelo Bene, with the flute, Gianni Trovalusci, a true virtuoso. In the second episode, entitled Solo, the dialogue (always sophisticated) is between the oboe (Christian Schmitt), the orchestra and a recorded orchestra. We then go to a Psalm in which the choir dominates. As if to juxtapose the psalm, the oboe (Christian Schmitt) intoned a Klage (lament) which precedes the Battle, a confrontation between orchestra and recorded orchestra. After the fight came a long monologue of Hyperion (who lost the battle), Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny), almost a tribute to Brahms where, however, the oboe excels in dialogue with the choir and the orchestra; it indicates man's struggle in the face of the lazy bliss of the gods. The conclusion, entitled Aria II, is the transcription of a soprano aria for bass flute, flute in G and orchestra of a page imbued with lyricism that accompanies the last monologue.

Copyright © 7 February 2020

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

FURTHER INFORMATION: BRUNO MADERNA