- Maria Nockin Chandler

- Armenia

- Aaron Rabushka

- Madame Butterfly

- Staatskapelle Berlin

- Intermusica

- Christian Immler

- Anatoly Alexandrov: Sonata No 14 in E

MET STARS: From 2002 until 2021 the late Maria Nockin reported from Arizona, mostly on live opera productions.

MET STARS: From 2002 until 2021 the late Maria Nockin reported from Arizona, mostly on live opera productions.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Improvisation in the classical world and beyond, including contributions from David Arditti, James Lewitzke, James Ross and Steve Vasta.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Improvisation in the classical world and beyond, including contributions from David Arditti, James Lewitzke, James Ross and Steve Vasta.

120 YEARS AGO

A snapshot of the musical world

at the turn of the twentieth century,

by GEORGE COLERICK

The last social era which no-one is still alive to recall is that from around 1900 until 1914, taking in what we call the 'Edwardian' era and a few more years to the outbreak of war. For this and certain other reasons, it may be remembered with nostalgia, such as a 'sunset glory of empire'. There was no radio, but famous performers were recorded acoustically, the sounds in part distorted, our earliest aural link with history. There remain quaintly static, dignified ancestral photographs, and those of the privileged classes, then almost tax-free, enjoying the good life to apparent popular admiration: poorer people in large groups, at work, watching football all dressed in Sunday best. Opulence and poverty, separated by a gulf, but everyone wearing some kind of hat.

For them leisure was more valuable than for us because most had long working days, and we might even envy their innocent pleasures or some of the entertainments, which had to be cheap. In the creative arts, those fourteen years were as eventful and exciting as any in Europe's history. Education and opportunities for participation had greatly increased the numbers of distinguished writers and composers; and they had reason to celebrate civilisation's spectacular progress through the nineteenth century. Collectively, there had never been sounds with so much confidence and splendour as the new music around the year 1900, with the largest orchestras ever used, and an attractive range of bands. Recorded music, existing in small quantities, was not yet a substitute.

To many people living in western Europe, war had become a romantic notion, soldiers dressing in fine uniforms to impress, their officers to feature at balls and on operetta stages. In 1914, Europe's young men marched off hopefully, just an autumn war to prove themselves to return home finally for Xmas. The unimagined death toll, suffering and squalor which followed was an obscenity which appeared to have no end, a testimony to human stupidity and the destructive urge, a denial of the civilisation so recently boosted. Popular music might seek escapism, but the new art music would never sound the same again.

It is a historical curiosity that so many great composers died and so many young ones appeared or reached maturity around the year 1900, and with arresting new styles of expression. They were to become the last of the late Romantic generation, but did not escape the spirit of the age, and with hindsight we look for reflections of changing realities in their music. There were also less obvious affinities in various styles.

The first decade witnessed Richard Strauss' sensational development of German music drama, and Mahler's evolution as the most controversial symphonist of his time. In Italy, the cult of dramatic realism, verismo, was being followed by several successful operatic composers; of them Giacomo Puccini would achieve most lasting fame with such emotive works as Madam Butterfly (1904) and Tosca. The first great school of Russian nationalist composers had died by 1910, and Stravinsky was about to emerge to be during the 1920s internationally the most influential of the Russians. Meanwhile, Rachmaninov had become Europe's leading composer-virtuoso, in one sense perhaps Tchaikovsky's successor, with a melodic inspiration and piano technique to win exceptional appeal.

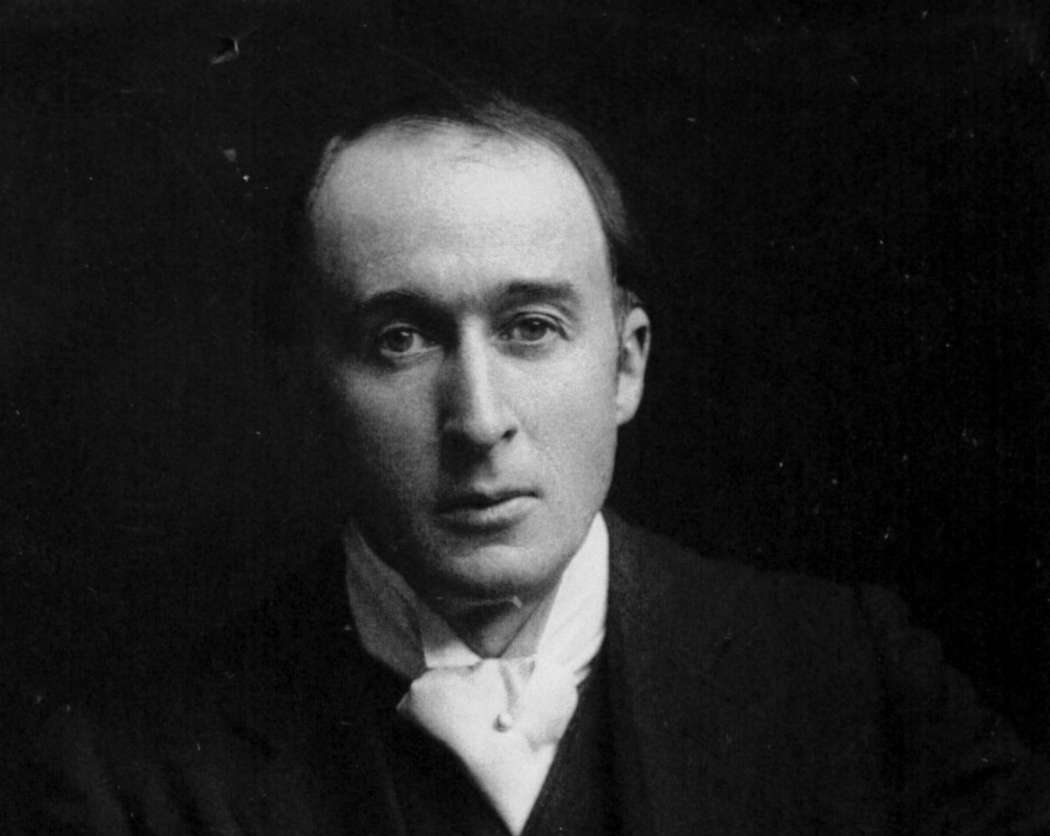

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

By contrast, the most disturbing note within the Romantic idiom came from Arnold Schoenberg in a unique chamber work. Transfigured Night (1899) concerns a woman confessing to her lover that she is pregnant by another man. It has a sweetness, but underlying is a poignant dissonance, wistful. Schoenberg had expressed a saddened human relationship with a sharper conflict of harmonies than had been previously accepted. In later works, he rapidly progressed to the point where he abandoned familiar melodic patterns. This became the most revolutionary step in all Western music; he and his followers would establish the 'Second Viennese School', to distinguish it from that of Haydn and Mozart.

French artistic impressionism was influencing the music of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, who both preferred to move away from classical rules of musical form. Debussy did not just find a new style but a new aesthetic. Listening to much of his music, such as the opera Pelleas & Melisande, was a different kind of experience - the moment the chord (vertical) had an increased importance in relation to the melodic (horizontal). His works for orchestra, Images and La Mer, were models of a new kind of expressive harmony, strangely evocative. Ravel fascinated with his use of modal scales, often suggesting the other-worldly, and an original use of orchestral colour. He invoked Spanish life in the opera Spanish Hour, and Ancient Greek myth in a lengthy ballet, Daphnis and Chloe. Vaughan Williams would study orchestration with him in Paris, returning home to create what had not been achieved in music before, a broad, vibrant impression of his city in A London Symphony (1908).

Debussy could have said it, but it was Sibelius who advised and asked an aspirant to be cautious in the use of notes; every one should have its own life. Several composers would often be identified by just one chord or their use of instruments. These would often be played at unfamiliar parts or extremes of their pitch, even disconcertingly, a trend much associated with modernism.

In 1899, Frederick Delius advanced towards international recognition with the tone poem, Paris, the Song of a great City. Born in Bradford, he had welcomed an escape from the industrial world when his father paid for his stay in Florida. There he learnt to value Afro-American music, then studied in Germany Wagnerism and the other fruits of the Romantic tradition. Absorbing this, by the 1900s he had broken away from society and its conventions into a uniquely private world, composing in moments of frequent elation inspired by nature and a kind of Pantheism. His works have a leisurely flow, extended melodies, soothing harmonies and often the lushest of orchestration, notably Sea Drift, Song of the High Hills and On hearing the first Cuckoo in Spring.

Frederic Delius (1862-1934)

Leoš Janáček (1854-1928) had made conventional arrangements of music from his home province, Czech-speaking Moravia, before making a radical break in style, when he began to base his melodies on the native speech rhythms. Most famous of his operas is Jenůfa (1904), a tragedy of peasant life suffering from village bigotry. His late works were startlingly original: a sequence of operas, passionate and on very realistic themes, but two with humour and strong elements of fantasy.

In Britain, composers Charles Stanford's and Hubert Parry's finer works are neglected now, partly because they are seen as 'Germanic', composed in the shadow of Brahms. It was unforeseen that one Edward Elgar (1857-1934) would displace them, achieving critical fame in 1899 with the Enigma Variations. This revealed a strong individuality which initially made a big impression in Germany, 'English', but as he implied, far from folk music. Large-scale compositions of great depth followed, symphonies and oratorios, to supplement the popularity of his marches and other light music. Wilfred Mellers comments:

He accepted Edwardian society as zestfully as Delius rejected it. Both took over the idiom of German Romanticism, Delius to express an egocentric isolation, Elgar to express a social conviction no less purposeful than that of Richard Strauss. That Elgar could use this idiom with a technical expertise equal to Strauss' was a remarkable achievement; he was able to assume the existence of a great symphonic tradition which had never happened in Britain.

He had the power to make us believe, momentarily, that the Edwardian world was as grand as his music; while at the same time he subtly suggests that in his heart he knows, and knows that we know, that the grandeur is in his imaginative vision.

London UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: WILFRID MELLERS