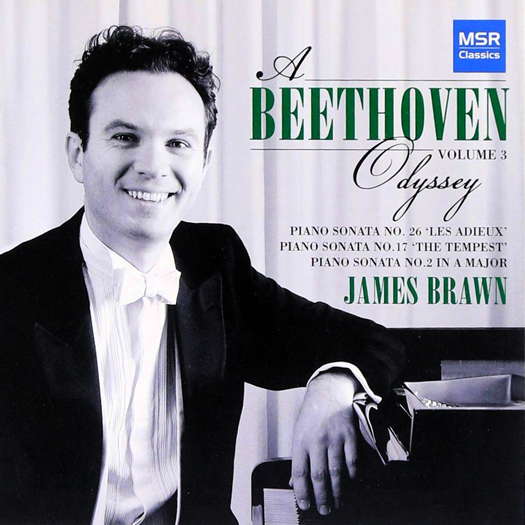

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

LIGHT AND SHADE

GEORGE COLERICK writes about

idealised beauty alongside the grotesque

in the 1951 film 'The Tales of Hoffmann'

In its first half century, the familiar motion picture industry achieved remarkably little to advance the mass appreciation of the other arts. One exception in the 1940s-50s was the Archers film company, led by director Michael Powell and his script-writer Emeric Pressburger. These men promoted Britain's creative prestige and increased cultural awareness in their films. Three with very high production values were most inventive in relation to dance, operetta and opera.

The Red Shoes was a ground-breaking dance fantasy and Oh! Rosalinda a witty adaptation of Johann Strauss' Fledermaus (1874), given a contemporary plot set in Vienna post-1945 under four-power occupation. A new conception was to integrate ballet with innovative film techniques into a classic opera, Offenbach's Tales of Hoffmann (1880). Several of the finest talents in the performing arts available in Britain of 1950 were brought in. Musical director and conductor was Sir Thomas Beecham; the one-time Diaghilev protégé Léonide Massine mimed three roles. The film has been an inspiration to many who followed, as testified five decades later by Martin Scorsese, who has recently been directing films about musicians.

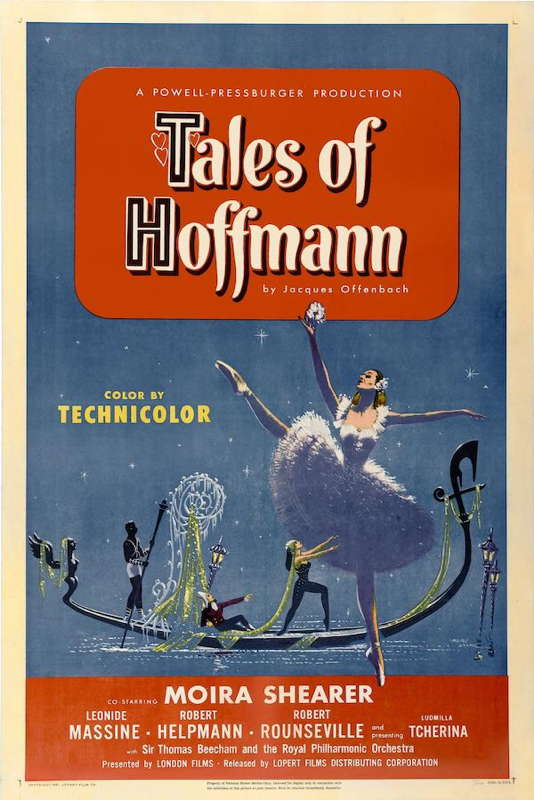

Poster for the 1951 film The Tales of Hoffmann

Early German Romantic E T A Hoffmann's stories of fantasy had been adapted as a play by Barbier and Carré, the librettists of Gounod's Faust, including one which had inspired Delibes' ballet Coppelia. The real Hoffmann was fictionalised as the protagonist, a foolhardy man doomed to failure. This was a difficult projection that few composers would have touched, demanding music in turn lyrical, farcical and ironic.

The hero cannot distinguish infatuation from love: one automaton and two women, relations in turn absurd, whimsical, and ill-fated.

He is to become the victim, hardly more than reacting to the manipulations of his rival, the classic antagonist who pursues him in varying embodiments, frustrating his love affairs.

Hoffmann has become obsessed with Olympia, a mechanical doll, the latest Parisian fad. She is programmed to waltz and say oui, but has to be wound up like a clock whilst performing. Hoffmann has been presented with rose-tinted spectacles seemingly by an optical inventor, Doctor Coppelius. Olympia sings, coloratura no less, and sweeps Hoffmann into a frantic dance until he is exhausted. After quarreling over copyright and a bounced cheque with her owner, Coppelius destroys her, the shattered remnants falling at Hoffmann's feet.

In Venice, Hoffmann visits a plush casino and fired with machismo, loses at the gambling table. He hopes for the ultimate consolation from the mysterious courtesan Giulietta, but this show is entirely set to the scheme of his antagonist, in another guise. Like Mephisto, his speciality is seizing men's souls, and he intends to add Hoffmann's to that of the freakish Schlemil who had been enslaved by Giulietta. She will do his bidding, acquiring Hoffmann's reflection, his moral self, so that he can be induced to commit a murder. The victim is to be the disposable Schlemil who has been watching insanely jealous as Giulietta vamps Hoffmann. So a deadly conflict is manipulated. Hoffmann snatches from his dying opponent the door key to Giulietta's room, rushing in only to find her gone.

In Munich, the Act where tender feelings uniquely surface, Hoffmann loves Antonia, who because of frail health is forbidden to sing. The sinister Doctor Miracle calls at her spacious home on the pretence of curing her. He conjures uo the voice of her mother, once a famous singer whose portrait is on the wall, then hypnotises Antonia to join her in an intense duet. At the peak, she has a seizure and dies, with Hoffmann rushing in too late.

He has been telling students these stories in a Bierkeller opposite the theatre where Stella, his latest enthusiasm, is singing in Don Giovanni. Hoffmann tells the comic-grotesque tale of Kleinzach, the 'little fellow', puppet-like. When he refers to his funny face, sa figure, this could equally mean her features, so he starts to sing Stella's praise, though the rowdy audience prefer the Kleinzach story. By the time she comes to meet Hoffmann, he is dead drunk and she walks off with the rival, now the urbane Councellor Lindorf. He had previously boasted that there are easier ways to possess a woman than love. This is a perverse morality open to several ingenious interpretations. Hoffmann is finally consoled by the Muse of Poetry who assures him of her love. Suffering will make him a superior poet.

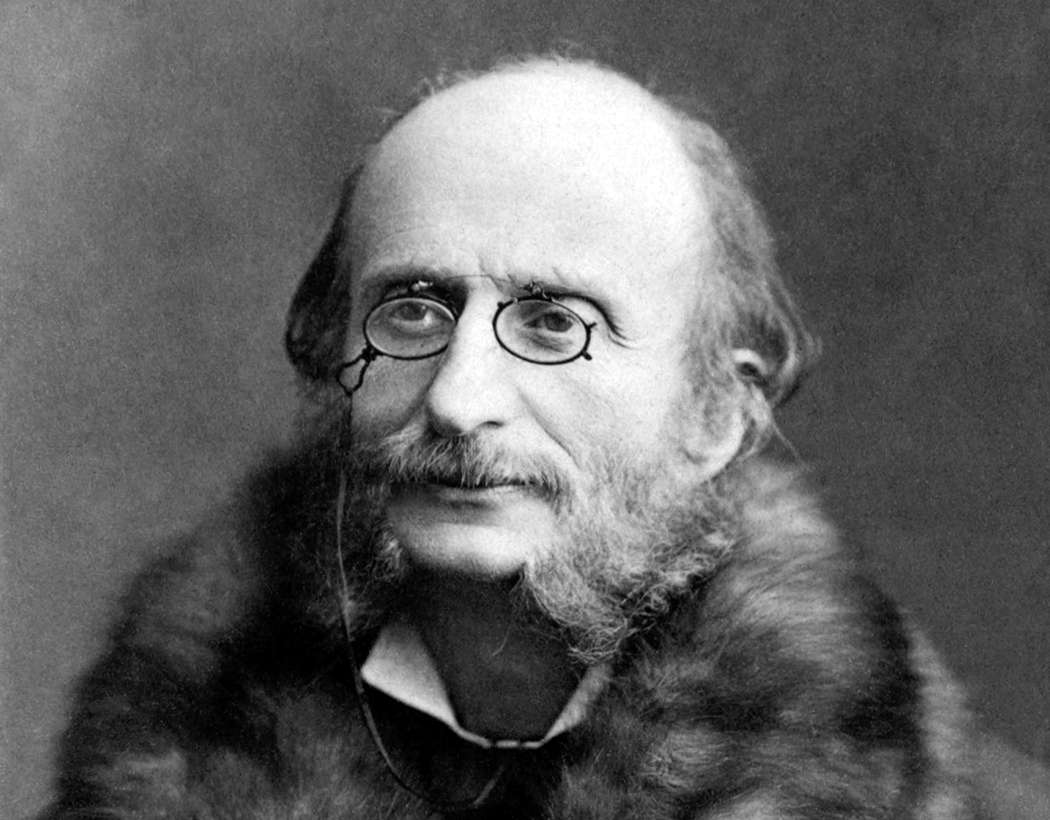

Offenbach was approaching this, his hundredth stage work and sixtieth year, but in failing health, with a race against time. His skill for parody would be brilliantly applied, moving from farce to tragedy, music to accompany a hero with the leisure to travel around Europe: Germanic drinking songs, a minuet and fleeting waltz for a Paris salon, Verdi-like fervour for the Venetian fantasy and an occasional Gounod-like pathos in the final scenes.

Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) in the 1860s

Though prolific in sensuous tones, Offenbach was better known for humour than sentiment, but there are many passionate moments such as Hoffmann's love duets with Giulietta and Antonia. From his German opera, The Rhine Fairies, Offenbach converted one piece destined to become the most famous of all barcarolles; it was first heard as a dream-like soprano duet at the start of the Venetian scene.

The lack of a definitive opera version gave extra interest to this filming, a sophisticated treatment of the macabre. The music was performed first then the ballet added. There was no spoken dialogue and nearly all the cast were singers or dancers who mimed the action. Stella's role was altered and enhanced visually into a famous dancer. Vistas are interspersed of her performing in a short ballet, with the opera's melodies adapted. It is choreographed to recall the style of Giselle (1842) but she wears tights fashionable for the 1880s in place of the tutu, with a pas de deux to a restrained variant of Hoffmann's Venetian romance, What rapture enflames my soul? Moira Shearer dances Stella and Olympia whose appearance is set within a marionette show. She is wilful, not programmed for flirtation, spinning with Hoffmann on an unending staircase until he collapses. This Act ends with horror, a bare leg twitching in mid air and the eyes of the severed head blinking at the spectators.

Here and in what follows, the singer Robert Rounseville's face reveals how far Hoffmann lives in his head, and arriving in Venice, he is scarcely aware of a discreet orgy going on around him. Then more intimately, magic takes over, to the symbolism of burning candles, as in the Diamond bass aria the rival bribes Giuliuetta into subverting Hoffmann:

Oh! Gleam with desire, in diamond the sun lies reflecting. So gleam with desire, with splendour steal her heart. As the moth flies round the candle, woman ...

In a scene attractively stylised, with moments of intense eye contact, Giulietta is briefly seen wearing a diamond necklace. Or is it just another illusion? Her role is played by Ludmilla Tchérina in an exquisite burlesque of a femme fatale, at first with apparent abandonment to Hoffmann's ecstatic romance, their duet reaching a peak for the time it takes until his reflection has disappeared. Then springing away from his embrace, coldly, she struts in triumph around him. For a moment, he regains his senses, alarmed at losing his reflection. Massine enters as Schlemil, an obsessive, humanity already drained from him. He and other sinister creatures press in upon Hoffmann, a threatening tableau which climaxes in an explosive septet. The doomed Schlemil duly makes a melodramatic challenge, the tension resolved as he and Hoffmann are rowed away along a canal to their duel. For the first time in the film, the rival is hooded as the Grim Reaper but as such, visible only to the audience. Now as if to be transported into a lagoon, Giulietta preens herself in a hugely ornate gondola with her decadent retinue, in picturesque silence indifferent to the fate of her lovers: a scenario that has surely been imitated in some later musicals.

The Munich scene is changed to a villa alongside a sun-lit Grecian amphitheatre, the lovers playing duets in Antonia's spacious home until disaster calls. By then Hoffmann has left on the arrival of her father who distrusts him. Doctor Miracle with fearsome incantations impels Antonia to sing with her mother whose statue he has brought to life. They are heard on a celestial stage, where magic violins accompany, but it is from a cliff that she is seen to fall to her death.

Of those who danced two years earlier in The Red Shoes, Robert Helpmann has the commanding acting roles throughout as the villain. He makes the film's first entry, surreptitiously, and is the last to leave, his plans achieved. Just before that, he peals off his three facial disguises to the barcarolle music introducing a second pas de deux.

The film is memorable for its sustained irony, rich imagery, rapidly changing backdrops, close-ups and exciting visual detail: the ornate medieval setting for the Nuremberg Bierkeller: a cameo danced by choreographer Frederick Ashton for the midget Kleinzach among giant beer mugs: the transformations seen through those rose-coloured spectacles: light and shade, idealised beauty alongside the grotesque.

London UK