- Berlin Philharmonic

- Sergiu Comissiona

- Giuseppe Sammartini

- Darius Milhaud

- Anatol Ugorski

- Enescu

- Collegium Records

- Ashok Klouda

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

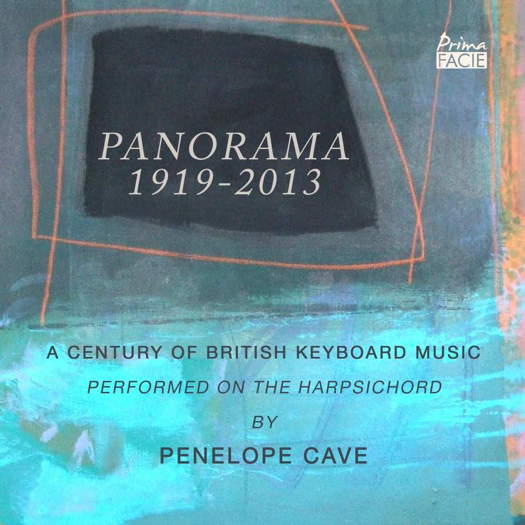

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

Well-chosen Contrasts

Sinfonia Viva is joined by Nottingham Harmonic Choir

and vocal soloists for an evening of

Sibelius, Mozart, Vasks and Salonen,

impressing MIKE WHEELER

This isn't the first time Sinfonia Viva has played a Sibelius symphony. I remember a very fine No 3 with the up-and-coming Edward Gardiner some years ago. No 4 is a very different animal: stark, austere, 'poignantly anti-heroic' in writer and broadcaster Stephen Johnson's description. That the orchestra and conductor Frank Zielhorst had the measure of its rarefied atmosphere was clear from the start. I don't know of any other symphonic opening like it - an attention-grabbing gesture that dissolves as soon as it lands. There was no shying away from the music's sheer strangeness, with a touch more bassoon colour in the very start than I've heard before, an apt grittiness in Deirdre Bencsik's solo cello tone, taut concentration in the exposed high violin lines, and a kind of aloofness in the three contrasted brass phrases that punctuate the movement.

In the second movement Sibelius seems to draw on his light music style, but to very different effect. Maddy Aldis-Evans' oboe solo was positively playful, but then the chill set in with the slower second half, here not so much resigned as biting back.

The cellos' first statement of the theme that builds gradually through the third movement set off in an almost unearthly calm, its grip on the music's structure becoming more forceful with each appearance. This may be Sibelius' most sparsely-scored symphony, but, paradoxically, there's so much detail to take in, like the solo woodwind phrases later in the same movement, clearly etched against the backdrop, and echoed by the piercing bird-cries in the finale. That movement's astonishing climax appeared not as a point of arrival, but a staging-post on the way to the oddly disembodied ending.

A publicity image for Sinfonia Viva, featuring Frank Zielhorst

In a brilliantly imaginative piece of programming, the Sibelius was paired with Mozart's Requiem, in the standard Süssmayr completion, for which Sinfonia Viva was joined by Nottingham Harmonic Choir, clearly fired up by its Director of Music, Richard Laing. The opening 'Requiem aeternam' moved with a steady tread rather than a heavy plod. A fierce, almost angry account of the 'Kyrie eleison' fugue led naturally to a blistering 'Dies Irae'. In the 'Tuba Mirum' the four soloists worked well as a team, beginning with bass soloist David Ireland combining cavernous sonority with agility across some wide melodic leaps. Tenor Konu Kim's clear, focused tone was a foil to Claire Barnett-Jones' warm, not too matronly mezzo-soprano, and soprano Elizabeth Karani's well-shaped phrases, though with a little more vibrato that I felt comfortable with.

The choir was forceful in the 'Rex Tremendae' and tender in the 'Recordare' while, in the 'Confutatis maledictis', the infernal whirring mechanism of the men's voices and orchestra was perfectly contrasted with the sopranos' and altos' plaintive 'Voca me'. There was a real sense of weariness in the Lachrymosa. The reference, in the Offertorium, to the lion's mouth prompted the choir to produce a definite roar, and 'Quam olim Abrahae' was not so much a plea as a forceful reminder to the Almighty of his (her? its?) promise.

There was punchiness in the 'Sanctus', offset by a not over-sweet lyricism in the 'Benedictus'. The three-fold' Agnus Dei' became increasingly urgent, and the concluding 'Cum sanctis tuis' fugue had just as much fire and determination as the 'Kyrie', whose music it reprises, capping a performance that had me wondering just how far we can take Mozart's expressive intentions at face value.

Advertising banner for the reviewed concert

Before the performance Frank Zielhorst announced a new partnership between Sinfonia Viva and local musical superstars the Kanneh-Masons, without giving details. It turns out that the family has, collectively, become the orchestra's first patrons, which has to be good news all round.

After the Mozart, the platform was reset for the After Hours concert, for which the Sinfonia Viva strings returned, this time with conductor Holly Mathieson.

Holly Mathieson conducting the National Youth Orchestra of Scotland

In Lonely Angel, Pēteris Vasks offers a vision of 'an angel gazing down on the world, concerned and hopeful at the same time'. It is a severe test for the violin soloist - it was written for Gidon Kremer - who, from a barely audible start, plays virtually uninterrupted for its twelve-minute duration, much of the time at a low dynamic level. Viva's leader, Sophie Rosa, met the challenge with aplomb, warmly supported by her colleagues.

Sophie Rosa. Photo © Helen Rae

Continuing the pattern of well-chosen contrasts, the evening ended with Esa-Pekka Salonen's Stockholm Diary. Edgy and restless, this is the exact opposite of Vasks' Lonely Angel, and with Rosa now in the leader's chair, the Viva players focused the work's energy, with its generally higher dissonance level, in which it was hard to avoid hearing suggestions of Bernard Herrmann's score for Psycho. The unexpected final moment of stillness was a tantalising glimpse of some other place.

Copyright © 14 November 2019

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK