DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

GENUINE ARTISTIC PERSPECTIVES

GEORGE COLERICK discusses

the music of Sergei Prokofiev

with reference to the Soviet authorities

the music of Sergei Prokofiev

with reference to the Soviet authorities

The originality of the style of Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) is easily recognised and dissected in his piano works, with which he burst into notoriety and lasting fame. Angular themes which last agreeably longer than expected, ironic tunes and 'wrong' notes, clusters of dissonant chords, fierce percussive technique, the briefest pause before a disarming mood change, the piquant effect of one hand playing major, the other minor. One movement might contain Russian folk rhythms, leisurely almost lazy passages, machine-like repetition and soaring lyricism.

If Beethoven's third Piano Concerto was an immensely enjoyable farewell to the classical, Mozartian concerto, Prokofiev's third (1921) looks back similarly to Romanticism. This is apparent in the dreamy, lyrical opening theme which awakes to lively transformations, and a final big melody, bathing in Rachmaninov-like glow. That and the cheeky neo-classical theme of the slow movement, with its impish set of variations, have made the work a concert-hall favourite. It is not far from the spirit of Shostakovich's First Symphony.

Prokofiev, drawn by Henri Matisse on 25 April 1921 for the premiere of the ballet Chout the following month

A youthful work which illustrates the extent and variety of Prokofiev's expressive powers is the pantomime opera, The Love of Three Oranges (1919), based on an eighteenth century Italian farce. The comic-hero prince suffers a range of moods which extend the conventional operatic aria to extraordinary degrees: excessive melancholia, uncontrolled laughter, fear of cosmic phenomena. It is late in the proceedings before he can declare his love for a princess, who has just been conceived in an orange, in terms which are passionate beyond belief. He rushes around the world on a wind-propelled machine, is almost eaten by a giant with a very low IQ and has to contend with an enemy who, taking the shape of a rat, brings chaos to the court. All this leaves so much scope for bizarre orchestration that these highlights are regularly performed in a symphonic suite now as well-known as the opera.

There is a surreal game of fate played with cards between two fantastically-dressed witches conjuring, in shrieking voices, the fiercest infernal voices at their command. The orchestra seems to split in half in splendid confrontation. Yet though the composer may not have wished it, the march was destined to become his hallmark: bold, spiky and manic, it may be suitably presented on stage with soldiers marching backwards at the request of the King of Clubs. No earthly monarch, president or general would dare include it in any ceremony.

All this might suggest suitable attitudes in a composer at the heart of the political revolution. In fact, Prokofiev was living among the artistic avant-garde and fleshpots of New York and Paris. He enjoyed composing for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, including the primitivist Scythian Suite clearly influenced by Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.

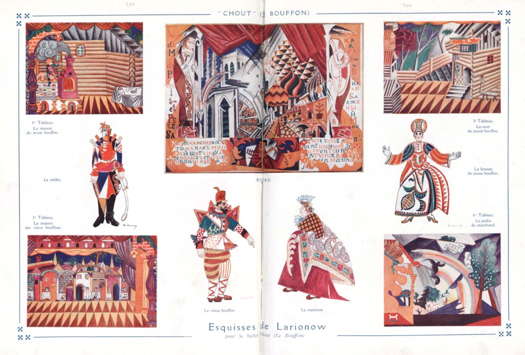

Sketches by Mikhail Larionov for the 1921 Paris premiere of Chout - Prokofiev's first ballet score for Sergei Diaghilev

He put some of his most complex but overwhelming music into an opera, The Fiery Angel, once more enabling him to enter the supernatural world and grapple with diabolical forces. Its theme mixes religion and sensuality, rising to the most frenzied scenes, and this 'decadent' story never found favour in the USSR so that Prokofiev did not see it performed. It was therefore valuable that he used it as material for the Third Symphony (1928). That and the Fourth, related to music for his ballet, The Prodigal Son, are very enjoyable works, but the big advances in symphonic style were to come nearly two decades later.

Sergei Prokofiev in New York, circa 1918

His sympathy for the revolution extended to naive efforts to write 'industrialisation' music, but that was regarded in Moscow as dilettantism. Yet he grew tired of the West, even though he had unrestricted travel between there and Russia, and returned home in 1936. He was becoming bored with the trendy fashions and attitudes in Paris, needed the musical inspiration of his homeland and hoped the requirement that Soviet composers should select uplifting and relevant themes would help him to achieve his most genuine artistic perspectives.

The earliest works to emerge from his new environment were therefore awaited with special curiosity. At least one English critic had described that popular Third Piano Concerto as totally devoid of feeling, presumably thinking of the Parisian fashions of the 1920s. He took back to Russia a new Violin Concerto, the Second, which was admired for its warmth and lyricism, a trend which he would continue.

As complement to that, he always had at hand sprightly melodies with an instant appeal, such as in the music for the satirical film, Lieutenant Kijé (1933).

Izrail Bograd's 1934 poster for the film Lieutenant Kijé, which satirises beaurocracy using a fictional character from the time of Russian emperor Paul I, who reigned from 1796 until his assassination in 1801

Specially popular has been his First Symphony, that had been concieved in the style of the eighteenth century, with a gavotte, a Haydnesque finale and symmetrical themes which are given piquant twentieth century harmonies.

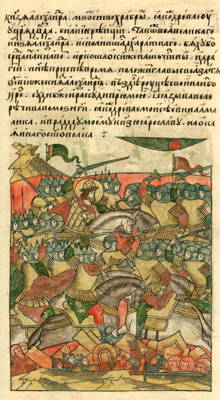

He threw himself into compositions supporting the Soviet system, of which probably the best was Zdravitsa (Greetings), a large scale choral work that also drew on the musical idioms of seven national groups in order to glorify the political union but was criticised in the West as praising Stalin. For the film classic, Alexander Nevsky (1938), he wrote one of the most effective pieces of descriptive music ever heard in the cinema. It portrays a ragged Russian peasant army rushing to fight the historic Battle on the Ice in which the pseudo-religious Prussian invaders are defeated and drowned. This cantata also displays a deep feeling for Mother Russia and that won the enthusiastic approval of Stalin; its moving choruses were performed widely by schoolchildren, especially during the war.

The Battle on the Ice, part of the Northern Crusades, 5 April 1242 on Lake Peipus, between Estonia and Russia, as depicted in the late sixteenth century illuminated manuscript Life of Alexander Nevsky

In 1948, as spokesman for the Composers' Union, Tikhon Khrennikov, who wrote not inconsiderable symphonies with a political, socialist-realist program, criticised, among others, Prokofiev for 'formalism', and having been too much influenced by Stravinsky. Prokofiev in reply wrote that to compose a melody instantly understandable, but also original, was most difficult, with the pitfalls of banality, sugariness and unconscious rehashing, whereas complex melodies were easier to find. He was determined to resolve this problem.

He rejected atonalism which had once attracted him. Constructing a musical work with the recognised key system was using a solid foundation, whereas building without tonality was as if on sand.

To explain himself further, he divided operatic accompaniment into that supporting action, recitative, and the song-like, which he called cantilena and arioso, including the typical nineteenth century aria. He had been criticised for using recitative too much, or almost entirely in the opera, The Gambler. Yet he recalled painful experiences of listening to almost one hour of Wagner without anyone on-stage moving. Opera-goers wanted action, which implied the use of recitative, and fear of immobility had reduced his use of cantilena. The letter song in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin resolved this problem perfectly and he would try to follow its example.

The most official interference Prokofiev had to suffer was over his plans for an opera on the sensitive theme of a war hero. Seen as being intensely political, it had to conform to accepted policy, and later critical opinion is that it ended up as one of his least satisfactory large-scale works.

For his adaptation of Tolstoy's War & Peace (1944), he was asked to give more prominence to the war, and less to the love story. His biggest frustration might have been that he saw neither of these works performed as he wished in their completed forms, though we can now see his achievement in War & Peace. In the patriotic tones of a pageant opera, it leads on from the style of Alexander Nevsky, balanced with a lyricism which suits the love entanglements. There is a moving scene in which Pierre confronts Natasha about her infatuation for a feckless married man. Surely a fulfilment of his wish for the desired operatic style.

Otherwise, there is not much evidence that the difficult poiitical climate affected badly the quality or nature of his output. He could always rely on official approval whenever he composed for children, and that was an undisputed benefit, such as the universally popular Peter and the Wolf with its inspired instrumental characterisation of the animals.

Front cover of the Peter and the Wolf Coloring Book, drawn from Nicholas Benois' 1947 Peter and the Wolf ballet at La Scala Milan. © 1985 Bellerophon Books

Nor were all obstacles political. The appearance of his Romeo and Juliet in Leningrad was delayed because the Kirov dancers complained it was technically problematic, diverging so much from the traditional ballet scores of Tchaikovsky and others. Yet it is now of course considered a classic, worthily placed alongside Swan Lake.

The most important developments of his last years resulted in three fine symphonies. The Fifth was lyrical and intense in ways that won approval as an example of what was hoped-for in Soviet music. The official comment which best summarised the Soviet position was clearly stated firstly in connection with Peter and the Wolf:

Here we have, in a classically pure and polished form, the melodic and harmonic style of the mature Prokofiev ... the gift for clarity and directness of a new Soviet symphonic style, free from both intellectual self-analysis and a tragic view of reality.

Within these terms was implied a generalised criticism of developments in form and content of the symphony among composers in Western Europe, where allegedly, such works had suffered a serious decline and only 'decadent' specimens were not being promoted.

Prokofiev was quoted as relating that symphony to the freedom of the human spirit. That and the Sixth were conceived in 1944 when all the leading Soviet composers had been offered a temporary home together away from the war, and were mainly concerned with works which would celebrate the return of peace.

Yet the Sixth Symphony (1947) had to be completed slowly after a severe heart attack, which may partly account for its more disturbing passages. In its slow movement, the feeling is such that a melodic reference to a noble theme from Wagner's Parsifal blends movingly.

The Seventh Symphony (1952) is in total contrast, attractively light-hearted, with percussive sounds such as we enjoy in his ballets. It was at first regarded in the West as not quite worthy of its momentous predecessors. Perhaps some critics did not appreciate the value of writing for young people, which had been the composer's intention. It should settle as a popular concert classic, inimitable Prokofiev.

In those years before his death - on the same day as Stalin - Prokofiev, born of a privileged family and at one time considered perhaps wrongly to be enjoying life as a 'playboy' in the West, composed in close consideration of the requirements of the Soviet state. Whereas Shostakovich, a son of the revolution from a loyal communist family, gradually moved towards a more private and questioning philosophy reflected in his later music.

From left to right: Soviet composers Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-76) and Aram Khachaturian (1903-78) in 1940 or 1945, by an unknown Russian photographer

Much has been written about the problems of both composers within the Soviet system. It may have provided them with, at best, the inspiration and, at worst, the nervous tension which found expression in some of their finest and most loved works.

London UK