DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

NO VULGAR COMMERCIALISER

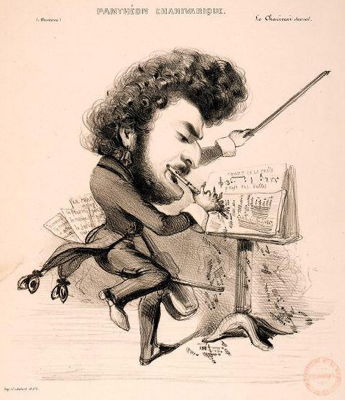

GEORGE COLERICK tells the story of Louis Jullien, a French impressario, composer and conductor famous in London in the nineteenth century

London's promenade concerts have now achieved over one hundred and twenty consecutive seasons and been broadcast to at least forty-five countries. The program format has generally followed a similar aim, which has been to preesnt mainly large-scale works by the great composers.

The initial concert of the 1895 summer season, though not intended to provide a pattern, cautiously paid tribute to the relatively low-brow tradition of promenade concerts which had occurred spasmodically during the previous half century in London and some other cities. What the new organisation had in common with the earlier conception was a policy of low prices but good quality of musicianship, and a one shilling entrance charge, enabling far more people to attend than at an all-seater event.

That first programme of 1895 played works by twenty-one composers of whom over half are still very well known and admired, whilst eight are forgotten: ten songs, several instrumental solos, a grand march, the highlights being the overture to Rienzi and selections from Carmen.

The pre-1895 promenade concerts in London are less well documented. They took place in theatres with the seats removed from the stalls, and offered the same kind of entertainment as many all-seater 'instrumental concerts'. An advertisement for two such events on Friday 20 February 1846 is specially eye-catching. These were to take place in Cheltenham, and without promenade facilities, the cheapest entry was two shillings.

The organiser was Monsieur Louis Jullien, famed for his activities in London and beyond throughout the 1840s and 1850s. He and some of his companions had travelled by the new railway system, of which a main-line extension to Cheltenham had recently been completed, so that its good citizens were specially privileged by comparison with most other provincial centres where such visits were not yet feasible.

M Jullien conducted, and of his seventeen credited assistants, nine had foreign names, a modest proportion even though most of them were almost certainly English. Signor Sivori was in the afternoon to follow Paganini's example by playing a fragment from Rossini's Moses in Egypt on one string, but without the help of the devil who was said to have presided whenever the old maestro performed that prodigious act.

Herr Koenig was perhaps the most valued member of the entourage, frequently enthralling everyone with a cornet-a-piston and playing his own composition, the Post Horn Galop, which is still a curiosity that everyone has heard but which has not earned him a place in Grove's Dictionary of Musicians.

The overture would be a lively alternative, from Auber's opera La Barcarolle or Flotow's Stradella. Beethoven would be represented by his triumphal march and a movement from either the 5th or 8th Symphony, sufficient for Cheltenham though London might hear a complete work occasionally with one or more military bands. Nor were the infernal elements to be excluded: the afternoon interval would be followed by four arias from Robert the Devil, an opera so notorious that as to be correctly written-up as Robert le Diable. Its creator had his name mis-spelt as Meybeer, a strange error concerning a man thought by many in the fashion of the time to be the greatest living composer.

For the evening, the diabolical Robert was to be replaced by excerpts from Donizetti's Lucia and Bellini's Puritani, but with clarinet solos instead of being sung.

Apart from cornet pieces by 'Roch Albert', M Jullien had composed the remainder of the program. His skill in special orchestral arrangements would be shown in his set of quadrilles from Verdi's popular Ernani, and his polkas would take us in our imaginations as far as Hungary, Bohemia and Douro. His Cricket Polka was not related to the hard-ball game but to Charles Dickens' Cricket on the Hearth.

He assures the readers that his new Redowa Valse will be as great a favourite in the 'Salons of the Nobility' as his polonaises and mazurkas. Well, a decade previously, the waltz had not been quite respectable because it enabled a man to get at least one hand onto a sensitive part of a woman's body, and even France's poet of the future, Victor Hugo, had condemned it as having a lascivious, circular flight.

M Jullien had immersed himself into popular British culture, resulting in a composition which had to be performed both afternoon and evening: the British Navy Quadrille. The fleet takes to sea, the men dance a hornpipe, the Bay of Biscay and the origin of gunpowder are celebrated in song, there is heroic declamation and Vulcan's Forge is not forgotten.

Seats for the afternoon show were sixpence more expensive than the evening one. Since it began at 1.30pm, why was it called a morning concert? This suggests linguistic association with the term matinée, but perhaps also that the idle Rich did not take breakfast until mid-day.

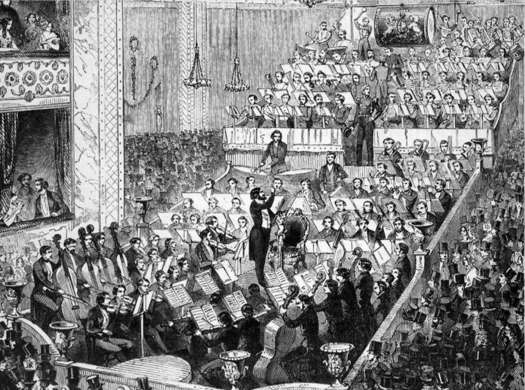

The great impressario-composer-conductor had numerous tricks available, including someone to play that mighty serpentine bugle, the ophicleide. His showmanship was nowhere better displayed than in his 'Concerts Monstres' which he had initiated one year previously in the comparative remoteness of the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens before 12,000 spectators. For the 1849 show at the same venue, advertised in English, excerpts from Meyerbeer's latest operas had to take top billing: his relatively unknown Prussian work, The Camp in Silesia, and almost straight from the printing press, his Parisian sensation, The Prophet. Alongside them, a composition which was much famed in its time but is now regarded at best as an interesting museum piece, Félicien David's symphonic ode, The Desert.

Twenty-four 'Roman' trumpets, led by the formidable Herr Koenig and double orchestra, were to play Bender's Triumphal March of Julius Caesar. Each bar of God Save the Queen would be accompanied by an eighteen-pounder canon, and there would be an enactment of the storming of Badajoz, presumably without the rape and pillage. The whole performance, including fireworks, would be over in five hours.

Though we laugh at some reports, Jullien was no vulgar commercialiser, but a daring entrepreneur with musical flair and vision, in addition to white conducting gloves and a jewelled baton. He could be very adventurous by introducing relatively unknown works, such as Beethoven's, and even attempted to popularise opera in the English language. The reward for that and bringing Hector Berlioz to conduct a London season in 1847 had been bankruptcy: but that had been a common experience in those days of bold private enterprise. He recovered in time to become very prominent in London's International Exhibition of 1851, where he exerted himself to achieve even wider fame. Even so, he was a fine example for other undischarged bankrupts not to follow.

Yet the final words on the 1847 failure can perhaps be left to Berlioz's distinguished Mémoires, if we remember that his writings had an imaginative force second only to that which he lavished on music. Jullien's invitation that Berlioz conduct an opera season, in English no less, at Drury Lane seemed to offer hope of relief from accumulated problems in Paris. Jullien had engaged an impressive ensemble, but allegedly had given little time to the choice of works. The venture depended on a new opera, The Maid of Honour, from Michael William Balfe, but it would fail to produce enough revenue. A safety net was to be Donizetti's Lucia, which could not take the estimated £400 nightly needed to cover initial costs. Jullien's final emergency plan was that Berlioz should prepare in six days from scratch the monumental Robert the Devil, including non-existing translation and stage effects.

Berlioz wrote that Jullien had an equally ineffective selection committee which included Sir Henry (Home, sweet home) Bishop, famous for his efforts to popularise operas through altering even the finest foreign ones before the British could hear them, and therefore a man who must have been anathema to Berlioz.

Berlioz wrote that he received no payment for London commitments, having written the sum off against Jullien's presumed 'madness'. Years later, he waived his claims when the debtor appeared in a Parisian bankruptcy court. Jullien's gratitude took the form of an improbable commitment; having recently heard the music of the spheres and received from God (seen in a blue cloud) an exhortation to make Berlioz's fortune, the wretched man then offered to 'purchase' his latest masterpiece, The Trojans, for 35,000 Francs. Jullien (1812-60) was by then on his way to a debtor's prison and death in an asylum.

London UK