The Beauty of Italy Captured in Sound

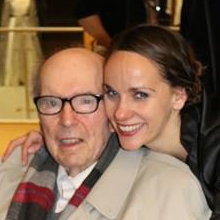

Arabella Teniswood-Harvey

plays piano music from Italy,

impressing RICHARD MESZTO

plays piano music from Italy,

impressing RICHARD MESZTO

The boot of Italy is home to more wonders, more splendours and more variegated history than whole continents. (I exaggerate, of course.) Perhaps it is a quixotic quest to seek to capture Italy at all. Like the Greek virgin huntress Atalanta, she always flies away.

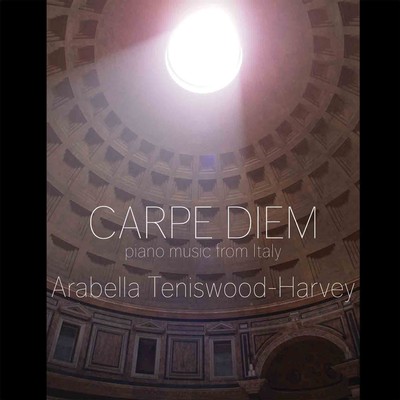

But, if you seek a small window upon that vast and magical land, then here is a place to start. But, notice that the image is a recent one: the selected music is no older than 140 years.

The earliest is Franz Liszt's Les jeux d'eaux à la Villa d'Este composed in 1877, but it is both one of his most mystical and most forward looking compositions. It is a gorgeous work, but there is a grave danger for it. Should the pianist play it as if it were an étude, then all hope would be lost. Indeed, most pianists play the work with a Czerny-esque belligerence: I will show you that I can play every tremolo perfectly evenly!!!!!

Something the great Nadia Boulanger thought about such an issue is relevant here:

'I recall a concert where [Busoni] played Liszt's 'Legend of St Francis of Assisi Preaching to the Birds' in a way that revealed the greatest depths in the work; listening to it, I tried to pin down what he did that made it seem so extraordinary. It wasn't until I had heard it three times that I realized he had managed the incredible tour de force of giving to the trills scattered all over the page the same number of notes - but this kind of feat didn't matter. Above all you sensed the unity of his interpretation.' - Bruno Monsaingeon, Mademoiselle: Conversations with Nadia Boulanger (1985), page 99

(As an aside, these days a computer can play the trills evenly, but will not necessarily attain transcendence. And if the even trills do not matter, why mention them and instead discuss the meaning of the phrase 'unity of his interpretation'? Well, it is easier to count the number of notes in a trill - even for the great Boulanger.)

The result of such an attitude would be a pianistic triumph and a poetical catastrophe. That is not to say one should be sloppy - why do pedants always jump to that conclusion? - but rather that mere evenness is but the beginning of the musical journey. (Re-read Boulanger, and note that today it is the norm to play the trills with exact repercussions, and it is not considered remarkable at all - but, the depth is sadly missing.) And here is an issue of sound and meaning.

The issue is one of a 'too up front' sound. This work (like Busoni's music according to some) must be played from behind a veil. Yes, the notes must be even, but it is not upon that - the evenness - that we must focus our attention. It is as Boulanger said. Sadly, modern recording does not easily allow this: the technology focuses us upon mere evenness and trivial exactitude. We become too close to the sound, too close to the hammers, too close to the percussive attack, and the mere addition of reverberation - now electronically done, based on usually feeble attempts by acoustic engineers to 'model' great acoustic spaces - the mere addition of that echoing noise, which will not change the quality of sound in the right way. The poor piano is heard too close up for its own good. Who will love another at first sight when the sight seen is of their beloved's molecules magnified 100,000 times?

But, clarity is the sine qua non of modern recording and modern listening. In fact, I don't think people can listen to a mere acoustic instrument any more. I have been to too many concerts now where the classical orchestra, ensemble, choir, piano and solo instrumentalists are miked and amplified for the 'benefit' of the audience. And this is done in halls with fine acoustics. But, people seem to prefer hearing sound though the medium of recording technology and amplification equipment. They prefer the shivering cardboard of an amplifying speaker to the vibrating wood of a violin or piano.

As Henry Cowell pointed out, 'A record of a violin tone is not exactly the same as the real violin; a new and beautiful tone quality results.' - Essential Cowell, edited by Dick Higgins (2001), page 254.

Now while Cowell may have preferred the recording, and I prefer the violin itself, we can agree that there is a difference.

And so, when we come to this performance, we must beware of the recorded sound: I suggest dimming the lights and turning the volume levels to very low, almost inaudible - cf Brian Eno's discovery of ambient music, or at least the specific inspiration for the 1975 album Discreet Music - and listening to the piano as if it came from a great distance away, across a vast gulf of Space, Time and Being.

Then one will hear a beautifully sculpted performance by the Australian (Tasmanian resident) Arabella Teniswood-Harvey (ATH hereafter), that captures the harmonic movement of Liszt's impressionism, along with his 'fioritura'. Just as with all mystical experience, one must make an effort to reach this fragile meaning, but if one does, it will burst forth in a glowing resplendence.

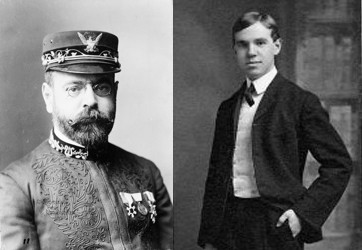

There is something utterly out of place about Charles T Griffes. How could he have been born and raised in the Gilded Age? One could equally imagine Lord Tennyson born in the American Wild West, slinging a gun, while writing poems of King Arthur. The result for poor Griffes is that one can't quite trust his inspiration. Was he wearing a mask? Did he really mean these things? They are tender, gentle, quiet, solitary and deeply reflective. Place him next to John Phillip Sousa and consider the disjunction.

In a time of almost feverish American motion, also known as 'speed', Griffes' music is a range of Slow Time. Indeed, Griffes' time is almost stopped. Each gesture floats in a moment of its own and hardly moves forward - this even in the most active sections. ATH captures this floating of time and leaves space between every gesture so that it may be considered, contemplated and soaked up. One luxuriates in her evocation of this rarefied sound world.

Ottorino Respighi also poses problems for consideration: an Italian who eschewed the voice and preferred the ways of Germanic instrumental composition. Here, he has based his composition upon Gregorian chant, but so altered and thickened is the texture that the voice is changed into just another instrument of a Wagnerian orchestra. ATH renders the density without loss of clarity and her sense of harmony is excellent. The balance and voicing of chords is ideal. In the second 'Prelude', I marvel at the bass note octaves: How does she get that sound? It's not a hammer blow, it's not a staccato, it's not an organ bass line, it is a semi-staccato that has sonority. I'm impressed.

The eponymous work by Michael Kieran Harvey (composed in 2015) begins with a virtuoso surge of clarity and sunshine, and then clouds appear to draw the mind back to solitary and inner matters. Intended to capture the towering of the pines of the Villa Borghese, the music swirls in vertiginous eddies that induces the surge for a life sought after. While the mystical, the beautiful, the resplendent are all features of Italy, forget not that it brought forth Futurism - cf F T Marinetti, circa 1909. ATH performs this demanding composition with superb command, having powerful control of chords and octaves, and in the sombre moments, a profound and subdued wisdom of sound.

Indeed: 'Seize the Day', and luxuriate in the Beauty of Italy.

Robinhood, Saskatchewan, Canada