DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

PROVOCATIVE THOUGHTS:

The late Patric Standford may have written these short pieces deliberately to provoke our feedback. If so, his success is reflected in the rich range of readers' comments appearing at the foot of most of the pages.

TEMPO CALCULATED

TEUN VAN DE STEEG finds evidence of

a missing link in our perception of music

a missing link in our perception of music

Introduction

Every music lover, amateur and professional musician is extremely aware that the success of any musical performance depends entirely on its presentation. In other words it can only succeed if it is performed in the appropriate manner. When we ask ourselves what does this depend on, we come up with the following essential characteristics:

- Acceleration and deceleration

- Difference in Volume (dynamics)

- Characteristics in articulation and phrasing

This survey is about acceleration and deceleration in a musical performance. Two well-known musical terms define this precisely: agogics and rubato. They express, in principle, that all music is performed on the phenomenon of acceleration and deceleration, which refers to very subtle changes in movement and is indispensable in any musical performance.

In the world of classical music it is commonly thought that musical deceleration and acceleration are merely arbitrary and based on 'habit', resulting from the musical performance itself by musicians from all over the world nowadays as well as in the past. At the same time it is assumed that agogics and rubato are dependent on musical feelings rather than timing. I rigorously oppose this viewpoint. My investigation proves that musical performance is based on stringent musical laws which, in their turn, are based on natural laws. This is my perception of a natural musical performance, which I will specify.

Music and convention

When ten musicians play Für Elise composed by Ludwig von Beethoven, we will notice subtle differences in all ten performances. This can create a major problem, as to which performance is the right one? A subsequent question might be: is there a perfect performance in our world of imperfection? Plato would say: 'yes there is, but only in a world of abstract ideas, not in our five senses'. However, can we assume that all performances are really perfect? A professional musician has to admit reluctantly that there is no ideal way to perform perfectly. At the same time he has to acknowledge that not every performance can pass the test of perfection. Some performances are not very good and others are even bad. In other words, musical performances can be judged differently, yet at the same time some can be more acceptable than others in the opinion of most musicians.

During a lecture on musical performance it was clear that there is no criterion for measuring sound to determine whether a musical performance is appropriate or even perfect. It is relatively a matter of good taste in the common world of music based on musical feelings which, in turn, reflect fashionable musical trends. When we consider the waltzes of Fryderyck Chopin for instance and realize they need to be performed in an appropriate way, we can perceive that every renowned musician uses his own freedom of movement which is attributable to subjective musical feelings and understanding. At least that is the reasoning of every musician, which, in my opinion fails undeniably. In other words, the assumed relationship between musical feeling and a convenient or correct musical performance is imperfect owing to the absence of a (musical-physical) measuring rod. However, I will demonstrate that such a measuring rod based on the law of physics does exist.

Music and notation

Having searched for many years to find an objective measuring rod to assess a musical performance, I encountered a very curious shortcoming in music notation and became determined to find the real connection between note values and what was really happening in the actual performance. Les us consider this in an almost phenomenal way. It is very curious to observe that in our assessment the notation of longer and shorter notes is quite the opposite. Just examine the two examples below in detail.

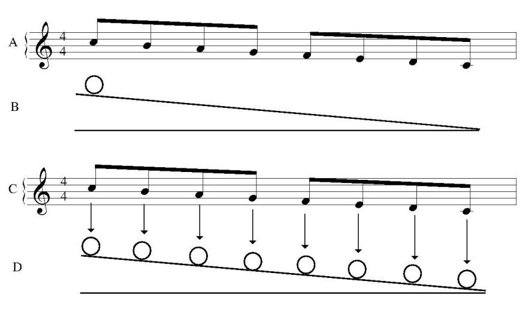

Figure 1. Image © 2019 Teun Van de Steeg

When we compare eight crotchets with eight quavers for instance, we can see that quavers cover twice the distance as crotchets. If eight crotchets cover a distance of eight centimetres then eight quavers cover a distance of sixteen centimetres. Here we can see a precise connection between music and physical reality. To clarify this, movement in music has nothing to do with musical feeling but rather a simple link with physics. I can demonstrate this quite simply on the piano. When I play a scale in crotchets with my left hand and one in quavers with my right hand at the same time, then the one with quavers covers twice the distance. However, in the printed form it looks quite the opposite. Movement in music has nothing to do with musical feeling but simply an understanding of physics. Just take a look at the two examples depicted in A, B, C and D below. In examples C and D it is obvious what we usually find in our notation. Optically it looks as if four semiquavers cover the same distance as one crotchet, but we realized this was not the case. A semiquaver moves four times faster than a crotchet and because of this covers four times the distance. Therefore it is equal to eight semiquavers. The main problem lies in our conventional notation, which does not allow different notes according different time lengths and distances. It is important for us to realize that there is a definite physical proportional relationship between movement and distance (of notes)!

There is also something strange in our notation. If you look at the following example you can see semiquavers in the right hand music. According to our understanding of music there are thirty-two notes altogether and we would wager that what we have seen is really correct, but realistically our interpretation is fundamentally wrong. I will demonstrate this in the following example.

Figure 2. Image © 2019 Teun Van de Steeg

In examples C and D below we can see 8 notes in a descending scale. That is optically true but for understanding our style of playing music is totally wrong. What we must try to understand is that examples A and B give us a realistic view. In fact, only one object is moving, for instance a marble, which is depicted in 8 different places. Our notation indicates that there are 8 notes, but in fact we are confronted by an object that is about to roll down. I hope that it is now realistic to see that we are dealing with movement, time and distance. To simplify matters, imagine a marble rolling down a hill, and if I make a picture of it every three seconds I will then have several pictures of one and the same object. Thereafter I can show 8 pictures in a row as if there are 8 different marbles but in actual fact there is only one! This very important observation shows us that in the case of movement, there is time and distance, not many objects, but only one!

Figure 3. Image © 2019 Teun Van de Steeg

I hope we can understand what is going on in the above example. Our music notation is a series of notes depicting moving objects in physical nature. Slowly but surely we can begin to understand that the notes in our music are notational fixations in a structure of notes, yet they can be compared with moving objects such as cars, bicycles, marbles, etc.

Score and physical nature

Our musical performance exists generally in a score. If we read the notes of Für Elise in a score we shall clearly recognise the following aspects:

- Movement

- Time scale (eg a piece of music lasts for two minutes and thirty seconds)

But we are still missing an essential component, distance, which is very strange. We realize that movement and time are involved but we miss the aspect of distance. Here we encounter an impossibility. An object that is moving over time undeniably covers distance as well, even when an object is moving in one place at the same time (a bouncing ball). In brief a moving object covers a distance over a period of time. A car that moves does so over time but cannot do so without covering distance. In other words we can recognise every moving object according to the moderation of physical law: movement = distance and time combined. And this is what happens in music. Musical movement is a blueprint of movement in physical nature.

As soon as we comprehend music as a physical movement we learn how to calculate music tempo exactly. It is clear that movement in music can be calculated in the same way as movements in physical nature such cars, bicycles, marbles, etc. It was Isaac Newton who formulated his three laws:

- First law: mass is slow

- Second law: F = m * a (F = Force in Newton; m = mass; a = acceleration in m/s2)

- Third law: action force is reaction force

Musical performance in a physical framework.

What conclusions can we draw from this? In the first instance we can comprehend that musical performance is a blueprint of physical nature. Secondly, it is a matter which can be calculated according to the knowledge of physical law formulated by Isaac Newton. The possibility to calculate the movement of cars, bicycles, pedestrians, etc is the same procedure used to calculate the movement in music.

The reader may think that he needs to have an intense knowledge of physics to understand this. First of all he might consider doing all kinds of complicated calculations. That would not be necessary. What I recommend is to imagine the musical movement as a movement in nature as we know it from experience. Real calculation is a procedure for the future and reserved for physicians.

In Conclusion

Until now there has been no clear explanation for understanding musical movement. Nevertheless, I am really convinced that only the physical approach is the appropriate one for understanding a musical performance. We have seen that our optical perception is not an exact interpretation of what happens in music. We have been able to conclude that there is evidence of a missing link which is the distance component. Now that we have put that right we are now convinced that musical performance, in principle, is based on the law of physical awareness which was initially introduced by Isaac Newton.

Now we only need to allow our musical performance to work in the same way as objects in nature move and project this into our consciousness. Then we will observe how closely linked music and nature are. Only when we realize this will our musical performance become easier to understand.

Netherlands