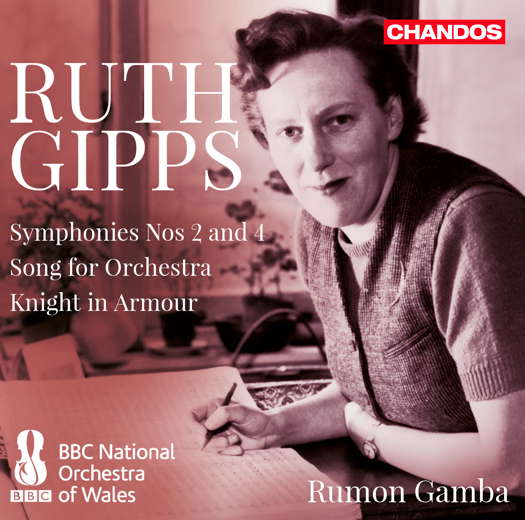

Dazzling Symphonies

Symphonies by Ruth Gipps,

recommended by RODERIC DUNNETT

recommended by RODERIC DUNNETT

The courage and innovation of Chandos Records in championing many who might be deemed significant composers of the mid-last century, and whose music, as new fashions took hold, became needlessly neglected, is one of the most admirable facets of the label's wide-reaching repertoire.

Dyson, Edgar Bainton, Rubbra, William Alwyn, Thomas Armstrong, William Lloyd Webber and Cyril Scott are just a few of the names into whose music Chandos has breathed new life.

One of the undoubted stars in their firmament is conductor Rumon Gamba, whom they have also promoted as the moving force behind their adventurous collection of British film music. And under his baton, some of the fire, flair and, conversely, tenderness of those scintillating scores finds its way into Gamba's championing here of two dazzling symphonies, plus two notable ancillary works, by Ruth Gipps: certainly one of the outstanding women composers of that era - 1921-1999; her centenary approaches; but also a magnificent technician - whatever her sex.

Chandos' rediscovery is, as always, apt and timely. Gipps was multi-talented; as an oboist (married to a clarinettist); as - from an early age - a revealing performer of piano concerti; as a choral conductor (and founder of choirs); as a teacher, who transferred from Trinity College to succeed her own mentor, Gordon Jacob, at the Royal College; and most memorably of all, as a composer of very obvious talent.

One is grateful, as so often, to Lewis Foreman, whose breadth of learning about English music has furnished here the most ample and perceptive notes about her life, achievement and these works here recorded. Taken altogether, as an introduction to Gipps' work, both text and music could scarcely be bettered.

Her achievements were multiple: she was, as he says, 'a byword for hard work'. And he nicely likens one passage - it could apply to others - to 'what one might imagine from a latter-day Holst', pinning down another likely influence as well as hinting at the sound world Gipps espouses.

There were five symphonies - she felt most drawn to orchestral writing, although the opportunities for performance grew fewer in the post-war period. The two offered here, Nos 2 and 4 - we hear the Fourth first - confirm her remarkable achievement from the outset: her First was composed when she was 20/21, the Second in 1945 in response to an invitation for works to celebrate victory in World War Two. Actually it is not especially vainglorious: the shifts of mood and constant variety of the writing, the transitions in dynamic and momentum, reveal just the kind of accomplishment that pervades her work. She wrote this (No 2) the same year that her First was publicly performed, by the City of Birmingham Orchestra (as it then was) under the enabling George Weldon.

Ruth Gipps fought articulately and energetically against the lionising of serialism and the avant-garde, and its consequences. But happily taste has since swung to the realisation that many of these ignored composers were in themselves a kind of avant-garde: their management of material, their mastery of symphonic (or indeed chamber) development, their command of idiom and their economy in handling motifs and patterns was nothing to be sneered at.

Gipps was abreast - it is clear here - of composers like Walton (who often comes to mind), Bliss, Sibelius, the Impressionists and a host of others. But her voice comes across loud and clear as an individual and quite insistent one. These symphonies actually work - the Second, cast in a single movement, producing interesting and original treatment. The sections within them compress, expand and interlink with a magisterial assurance, wit and evident feeling for a range of expression. These are subtle and clever works, as well as approachable ones.

It was to Bliss that she dedicated her penultimate Symphony, the Fourth, Op 61, which dates from 1972. There is doubtless a measure of added maturity here from a composer who wrote her First some three decades earlier. But essentially we are hearing the same voice, the same freshness of harmony, the same immensely satisfying approach to orchestration: the ingredients of the Fourth are in fact heralded in the Second, and, one gathers, the First also.

The sensitive opening bars of No 4 are wonderfully hushed and evocative, even though (unlike some of the slow movements on this disc) it soon starts to swell, then subside again. Several layers seem to move in contrast to one another, creating a kind of (at least) proxy-bitonality one finds throughout both symphonies. This intertwining, especially of the woodwind, has something of Stravinsky. And it soon gives way to a fugal, or quasi-fugal sequence that could, as Foreman reminds us, be straight out of Walton (Spitfire).

Her interest in the woodwind perhaps reflects her own expertise as an orchestral oboist and cor anglais soloist; she seems to have a natural affinity for making her most dramatic gestures here rather than in the strings. Solos galore burgeon and disappear. Some of her most engaging touches are for the tuba, which gets a whole tune to itself, something Vaughan Williams would have approved of. Both this and much else throughout the disc has a kind of yearning about it; not sentimental, but a feeling generated largely by sensitive control of pace and dynamic.

Listen — Ruth Gipps: Moderato - Allegro molto (Symphony No 4)

(track 1, 1:54-2:58) © 2018 Chandos Records Ltd :

It is worth advancing that, while Gipps' orchestral writing for full forces has a command and verve all its own, her writing for reduced textures feels, time and again, truly inspirational. The Adagio here fits that bill: woodwind soloists take over from each other with the elegance of a balletic handover; the music seems to be feeling its way, even in the più mosso. The valedictory harp could be one of those Holstian moments alluded to.

Listen — Ruth Gipps: Adagio (Symphony No 4)

(track 2, 0:01-0:54) © 2018 Chandos Records Ltd :

The third movement is marked Allegretto, but is in fact much more than that: like the fugue above, it reveals how skilled Gipps is at generating a dancing scherzo movement: revelling, impish, urgent. Once again, it is the BBC NOW's wonderful woodwind and brass that make the running. An oboe solo launches the last movement, achingly beautiful, recalling some of the mystery of the Fourth Symphony's evocative start.

Now at last first the lower, and then the upper, strings come into their own, the pace alternating between quick and slow passages. This extract gives some idea of the effect:

Listen — Ruth Gipps: Finale (Symphony No 4)

(track 4, 3:32-4:33) © 2018 Chandos Records Ltd :

The skittering paired clarinets which emerge from this are lightly accompanied with a beautiful finesse. It's this refined aspect of Gipps' orchestral deployment that attracts time and again. I tried to come up with a parallel, and the one that occurred to me is Nielsen's Sixth - the one that eschews the full-blooded build-ups of his mighty preceding two symphonies, and where Nielsen adduces textures as light and impish as (say) members of Les Six.

There follows a work from the very start of Ruth Gipps' career, Knight in Armour, a tone poem that she composed mostly when aged nineteen. Sir Henry Wood, no less, premiered it two years later at, amazingly, the Last Night of the 1942 Proms. A programme note by the composer, cited here, indicates how the idea was rooted in a rather alluring painting - The Young Warrior - by Rembrandt, almost nineteenth century in manner, onto whose outward bravado she has latched the story of Lancelot and Guinevere, so as to generate a solo woodwind conversation - oboe and cor anglais, her own two orchestral instruments. There is plenty of armorial bombast - but by no means only that.

The same Gipps signatures are prominent here - interleaved woodwind, prancing brass, and an oboe solo as magical as Debussy's sultry afternoon (L'Après-midi). The sheer competence here - Lewis Foreman alludes to 'its personal voice, confident conception, and vivid writing for the orchestra', all manifestly true - greatly impresses. Gipps' talent for making subtle yet smooth transitions in speed and dynamic, so notable in the eight parts of Symphony No 2, below, are already evident here in the tone poem, and are in fact essential components of her approach. The Fourth Symphony actually has twenty-eight individual sections; the Second, sixteen!

The hefty crescendo that is reached near the end dies away to nothing: unexpected soft endings are arguably another of Gipps' trademarks. It is as if to say, even in 1942, life is not all bombast: there is peace and quiet in the end.

Symphony No 2 abounds in these kinds of contrast. A blaring opening - not so much Les Six as a related composer, Martinů, springs to my mind - yields to light strings, overtaken by woodwind which goes on to sing a kind of exotic aubade. The next burst subsides into a cor anglais solo, immensely moving, and a hint of solo flute which will play a role two sections after, in a subsequent andante, where it sounds not so much maestoso (as marked), but reflective.

Listen — Ruth Gipps: Allegro moderato (Symphony No 2)

(track 7, 2:11-3:05) © 2018 Chandos Records Ltd :

The Tempo di Marcia (section 4) is a very light-stepped scherzo that grows into a jolly, prancing pirouette: one can imagine it in Vaughan Williams' view of London. Gipps writes for the piccolos like fifes: great fun. She also, one notes, likes to use the trombone as much as the horn for ponderous brass solos.

Listen — Ruth Gipps: Tempo di Marcia (Symphony No 2)

(track 9, 0:16-1:19) © 2018 Chandos Records Ltd :

The real slow section, marked Adagio, is wistful: the opposite of the more proclamatory music that litters this piece to reflect the harsher experience of war, to celebrate whose conclusion Symphony No 2 was composed.

There is more dance, and then a passage marked Appassionato. But more striking is the short finale, where delicate strings etch out a feel of laughter - perhaps joy at final victory, as Gipps allows herself to let rip with something approaching a Dam Busters march.

Ruth Gipps' passion for solo instruments shines in the oboe part of Song for Orchestra, a work dating from 1948 and premiered (like the First Symphony) under the baton of George Weldon.

Listen — Ruth Gipps: Song for Orchestra

(track 14, 0:01-0:44) © 2018 Chandos Records Ltd :

As may be heard, Gipps can harness modal elements into her construction of melody, though is quite often content to work within the normal harmonic scale, creating intensity by the quasi-bitonal accompaniments she structures below. Is this anti-modernist, so called 'cowpat' music? No. It conveys as much energy and artistry and expressiveness today as it did the day it was written.

Coventry UK

CD INFORMATION - RUTH GIPPS: SYMPHONIES NOS 2 AND 4 ETC

ARTICLES ABOUT WOMEN COMPOSERS