- Harrison Birtwistle

- Bantry House

- Werther

- Slovakia

- Kennedy Music Group

- Denmark

- Liechtenstein

- Marcy Stonikas

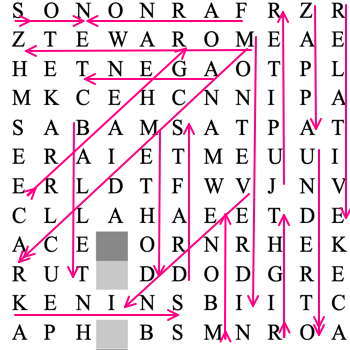

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The Creative Spark, including contributions from Ryan Ash, Sean Neukom, Adrian Rumson, Stephen Francis Vasta, David Arditti, Halida Dinova and Andrew Arceci.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The Creative Spark, including contributions from Ryan Ash, Sean Neukom, Adrian Rumson, Stephen Francis Vasta, David Arditti, Halida Dinova and Andrew Arceci.

A Sumptuous Programme

RODERIC DUNNETT reports from the 2024 Three Choirs Festival in Worcester

If Scotland has enjoyed three weeks of Edinburgh, and The Albert Hall countless days of the BBC Proms, is there an annual British festival outside London whose awesome programme of concerts can possibly rival the impact of those extensive, enviable events?

The answer is yes - definitely. The Three Choirs Festival can claim to be the world's very oldest Festival, its first dating from most likely Queen Anne's reign, roughly in 1710; or if not, then took off in George I's, which began in 1714.

The Worcester Three Choirs Festival opening celebration.

Photo © 2024 James O'Driscoll

Every summer between late July and August the organist (Music Director) of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester cathedrals - this year, Samuel Hudson at Worcester - designs a sumptuous programme of massive choral events, chamber and instrumental music, organ recitals, polished chamber choirs and chorale concerts, late night happenings, lectures, plays, and much else. Every day - morning, afternoon and evening - is packed.

Samuel Hudson conducting the opening celebration

of the 2024 Worcester Three Choirs Festival.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

This includes the daily Evensong, with Worcester's Nicholas Freestone the organist: an appropriate tribute to Edward Bairstow (born 1874); a remarkable discovery of the seventeenth century composer John Reading (born c 1645 - organist of Lincoln, Chichester and Winchester); the sadly missed William Mathias (1934-92), and Donald Hunt (1930-2018); a celebration of the festival's much-valued and generous American friends (another anniversary - their tenth year); and conceivably most treasurable and exciting, a new set of Canticles by Ian Venables.

But the most important feature of this wide-ranging festival is the bringing together, in a massive deploying of the unified choral societies of all three cathedrals - to perform large scale works, both traditional - sometimes rare - and contemporary. The impact and high quality of this giant ensemble is astonishing. For the vast audience, the experience in the magnificent cathedral acoustic is invariably thrilling.

And so it was in the festival held at Worcester this year. Following the Opening Celebration (and prefacing Widor's Mass - a dazzling and unusual choice - at the Festival Eucharist) this year's pioneering director Samuel Hudson programmed from the start substantial uncommon works by two of the major composers whose anniversaries are celebrated this year: Stanford (died 1924) and Holst (died 1934; Elgar and Delius of course also died the same year).

The principal event honouring Stanford, conducted by Hudson himself (as were several of the week's outstanding performances) was his Stabat Mater, a full forty-five minutes long. The strikingly (and attractively) extended prelude had, unexpectedly, a certain amount in common with Wagner - not an association commonly reognised, Stanford being more compared to Brahms. This early twentieth century work emerged as a masterpiece - strong on drama, well driven, fresh, energised. Solos soon take charge - a spicy cor anglais, the soprano (the superb Rebecca Hardwick, exciting, forthright, gripping) heading a long, operatic initial quartet, then a steadying, restrained mezzo 'Quis est homo' (Marta Fontanals-Simmons); plus more finely conceived, appealing orchestral interludes, a forceful tenor lead ('Eia Mater') for the commanding tenor Nicky Spence, with an alluring harp link, and just as desirable bass (Themba Mvula) at 'Tui nati vulnerati'.

C V Stanford's hugely rewarding setting of the Stabat Mater with soloists and the Festival Chorus conducted by Samuel Hudson. Photo © 2024 James O'Driscoll

Stanford's finale ('Virgo virginum') was notable for the splendid role allotted to the tenor and bass, not just joyous but at one point positively explosive. But notable was the, one might argue, brilliant way Stanford shares the chorus parts around, interweaving them expressively, and indeed cleverly, from voice to voice, and the variety he achieves overall, so many details of which Samuel Hudson revealed. This work's potential was actually unveiled more than twenty-five years ago on a Chandos recording by Richard Hickox and the Leeds Philharmonic Chorus (CHAN 9548) - appropriate as once Stanford was himself that chorus's conductor. But this magnificent, exciting Three Choirs performance emerged easily on a par with the recording.

Of special, added value, and hugely instructive, was a well-attended lecture on Stanford and his music by the composer's biographer Jeremy Dibble. Dibble is the world expert on Stanford (as also Parry and Stainer), and to have his versatile insight was a very considerable bonus, expounding most articularly Stanford's importance as an inspired composer as well as, famously, the teacher of many of the next generation's leading composers.

A superb lecture on Stanford by biographer and world expert Jeremy Dibble.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

Aptly, Holst played a major part all this week, in all different genres. Two major choral works at the festival's outset gave him especial prominence. The first, under Hudson, the same night as the Stanford, was The Hymn of Jesus. Vividly prefaced by two Easter plainsong hymns, it opens onto a fortissimo, climactic acclamation (with sopranos or trebles soaring above) offset by a most expressive pianissimo. The contrast between sections - a violent beat ('Divine Grace is dancing' - it does just that), heralding the empowered, whirling extensive and raptly repeating extracts from the Apocryphal Gospel of St John (including a finessed trumpet interspersed), and the exciting proclamation at the close, were all rivetingly sung - and exhilaratingly conducted. A marvellous, ecstatic work, and a really fine performance.

It fell to Geraint Bowen to introduce the exceptionally unusually heard full-length Holst oratorio, The Cloud Messenger, the following night. It's a tall order, needing careful managing, and that Bowen certainly achieved, perhaps especially because he managed to produce from the hard worked yet admirably articulate choir so many passages kept soft, quiet and virtually confiential from the text, which Holst himself, as so often passionate about oriental poetry - compare his opera Savitri or many Songs from The Rig Veda - translated from the Sanskrit. Thus the chorus's 'I was like you', the rocking 'They sat at our table' and the exquisite 'I love you, girl' are all transmitted immensely softly - almost at a whisper - highly effective; while the work expands latterly to a strong forte both midway and during the late entering solo -lustrous mezzo Beth Taylor. Holst uses tympani, bells and more - and some striking modality before the terminal brass blast - to generate variety.

The Three Choirs Festival Chorus in Holst's full-scale oratorio The Cloud Messenger, conducted by Geraint Bowen. Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

The substantial works by Stanford and Holst were prefaced by broadly fifteen minute contemporary pieces, essentially relating to the festival's principal theme, which this year dwelt on nature, the damage it suffers, and the urgent need for its preservation. The Imagined Forest by Grace-Evangeline Mason proved an exquisite work, doubly noteworthy for its enchanting violin solo by the sensational Leader of the Philharmonia Orchestra, Zolt-Tihamér Visontay, who contributed numerous gorgeous solos during the week. Nathan James Dearden's enchanting five movement commission is entitled messages. What impressed perhaps most was the sheer quality all week of these well-chosen, persuasive, carefully worked pieces. And in each case, it was the full evening audience which was treated to, and it seemed, appreciated these contemporary items, of which there were several more.

The most extensive, full-length, ultra-modern work - or might one say poem - some three quarters of an hour in length, was by the American composer Sarah Kirkland Snider. Entitled Mass for the Endangered and again conducted with crucial precision and refinement by Samuel Hudson, it expounds a substantial text by author and fellow musician Nathaniel Bellows. Snider intersperses fresh, inspiring and originally, fascinatingly adapted sections from the Mass; the freshness in Bellows' text stems from notable, indeed remarkable adaptations and unexpected verbal developments - for instance his novel treatment of the Agnus Dei. The Credo is an entirely innovative exploration, resulting in a kind of pleading, or assertive, Benedicite ('we believe'), in various formats, more than twenty times.

Samuel Hudson conducts the dramatic performance of Sarah Kirkland Snider's Mass for the Endangered. Photo © 2024 James O'Driscoll

And Snider's music? Endless invention and variety. An extraordinarily effective use of piano, often strikingly exposed and fabulousy played. A notably insistent Kyrie from a very alert choir. A Gloria unusually quiet, pianissimo, with harp solo and soft or even secretive women's chorus. Violins sharing the unusually devised Alleluia and its intense, evocative if elusive script ('Contour, carve, corrode - breathe through camphor' ... with men's voices ... 'Hearth of stone, of tar, of lava ... Fracture, foist, defoul'). Compare his unexpected version of, again especially, the Credo with its rocking strings ('Land limned on loam, haven to the harmed ...'). What did it all mean? At times, difficult to say. Yet it was somehow compelling, thanks to Snider's incisive, deft and precise use of the text. Yelping flutes and piccolos, breathtaking orchestral invention (again in the Credo); the contrast of delicate and joyous in the choir's Sanctus and Benedictus. And the electrifying feel of the much altered Agnus before a hugely effective fade out.

It would be a mistake, indeed a serious oversight, not to pay ample tribute to the programme of daytime concerts, which play such a significant role in each year's Three Choirs. Before the Snider, also in the cathedral and enhanced by its mighty acoustic, Christopher Monks directed his first-rate Armonico Consort in 'The Forgotten Scarlatti', which made a case for Francesco (1666-1741), younger brother of Alessandro and uncle of Domenico. And what an impression they made: the undoubted quality of Francesco's works, Dixit Dominus and his sixteen-part Mass, was irresistibly proven by this splendid, formidably precise and meticulously trained ensemble.

Christopher Monks introduces Scarlatti with his sizzling Armonico Consort.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

Elsewhere, at St Mark's Church, the violinist Thomas Gould and his piano accompanist Gwilym Simcock also offered three sonatas from another famous family, in this case by Arcangelo Corelli (climaxing with his superb Op 5 No 12, 'La Folia'). Fine repertoire, perfect playing.

Indeed the well-planned variety of daytime concerts was admirable. Another visiting choir, the highly capable Carice Singers, shone in an inspired, proficient modern programme, notably incorporating Anglo-Japanese Ben Nobuto and Luton-born Robert Crehan, both born in the 1990s; while the five-strong Corvus Consort - their programme entitled 'Byrd takes flight' - focused as one might expect with great insight into the Elizabethan era - Tallis and Byrd, with flute and saxophone in attendance. The cathedral Lay Clerks, it should be said, in a similar period and very attractive late night programme, proffered us Tomkins, Sheppard, the delightful German Johannes Eccard (1553-1611), from Bach's Thuringia, and the opulent Lodovico da Viadana from Mantua (c 1560-1627).

The Elias Quartet included, to great effect, Judith Bingham's dramatic and intensely exciting, almost Bartókian clarinet quintet Elsewhere (Robert Plane the clarinettist), while the Heath Quartet matched them with A Life Cycle, a vivid premiere from Joe Duddell, and very significantly, the half hour work Patrol by the late Steve Martland - another anniversary, born 1954. They also introduced a ten minute festival commission, O dreamland, by Luke Lewis, who hails from from West Wales; while Tippett's Second Quartet verged on the sensational. An intriguing, very full and very alluringly sung solo programme, including music by several women composers, came from Nigerian-American soprano Francesca Chiejina (with pianist Jocelyn Freeman), a marvellous perfomer of richly appealing presence, who later made a very welcome reappearance as one of the evenings' soloists (in Rossini's Petite messe solenelle).

The four Rossini soloists - Francesca Chiejena, Claire Barnett-Jones, Nicholas Mulroy and James W Hall - with conductor Geraint Bowen.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

Four organ recitals, including the usual three for younger executants, ranged from John Bull and Buxtehude - plus, intriguingly, the little known William Tisdall - to skilled arrangements (played by Roger Sayer) of three movements from Holst's The Planets - not just Mars and Jupiter, but more fascinatingly Venus as well. But also definitely a major event was a performance by Tom Bell, in nearby Pershore Abbey, of the entire Livre du Saint Sacrement by Olivier Messiaen, nearly two hours long, and of course some riveting playing by Nicholas Freestone in the daily Evensong.

The other main anniversary being cheerfully celebrated, aptly with several works, was that of Judith Weir: the seventieth birthday of the recently retired Master of the King's Music. Interestingly, especially appealing was a piece just four minutes long, entitled Still, Glowing, for small orchestra. A wonderful work, expressive, hushed, murmuring, inviting. O Sweet Spontaneous Earth unveils magic with enchanting harp, and gradually blossoms into enraptured joy.

The inspired, enriching text for his second New Testament oratorio The Kingdom (following The Apostles) - this year's festival's thrilling finale - Elgar chose, or devised, himself. It too focuses on the calling of his disciples, Parts one ('In the Upper Room'), three ('In Solomon's Porch') and four 'At the Gate Beautiful' in particular provided opportunities of great emotional intensity, and at key moments power, for the magnificent (and indeed massive) Three Choirs chorus, enabling them at every stage to dramatise the oratorio's brilliant, vital and exciting New Testament narrative.

Perhaps above all it's the soloists who play the most important part in the unfolding drama: from the start, St Peter (the wonderful Uppingham School-trained tenor Toby Spence), the - both superb - two Marys, soprano and contralto (Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene - Anita Watson and Rebecca Afonwy-Jones), wonderfully expressively paired in The Kingdom's elegant, flawless second passage 'The Morn of Pentecost'.

Contralto Rebecca Afonwy-Jones was also staggeringly moving in Elgar's part four, the most famous of all solos, 'The Sun goeth down', leading to The Arrest and a vital, ecstatic chorus 'The Gospel of the Kingdom'. Peter is important again in Elgar's final section ('The Upper Room'), where he joins with John (baritone Ross Ramgobin) in a deeply moving shared finale. Every detail and aspect, and every subtlety, of this unforgettable work shone forth, with the Philharmonia equally on top form under conductor Adrian Partington.

The festival's thrilling climax - Adrian Partington conducts Elgar's oratorio The Kingdom, with all four soloists and the Philharmonia Orchestra.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

Without doubt an exciting event shone out with a full length work by Bob Chilcott, who has enjoyed great success and popularity over recent years. His wealth of warmly acclaimed sacred music includes the St John Passion, the Christmas Oratorio, a Requiem, the Little Jazz Mass, Canticles of Light and Move him into the sun, a touching centenary commemoration of Wilfred Owen. Over twenty of his carols are recorded on The Rose in the Middle of Winter, a brilliant, exhilarating recording by the choir Commotio (Naxos 8.573159). An exquisite secular collection appears on Making Waves (Signum SIGCD142).

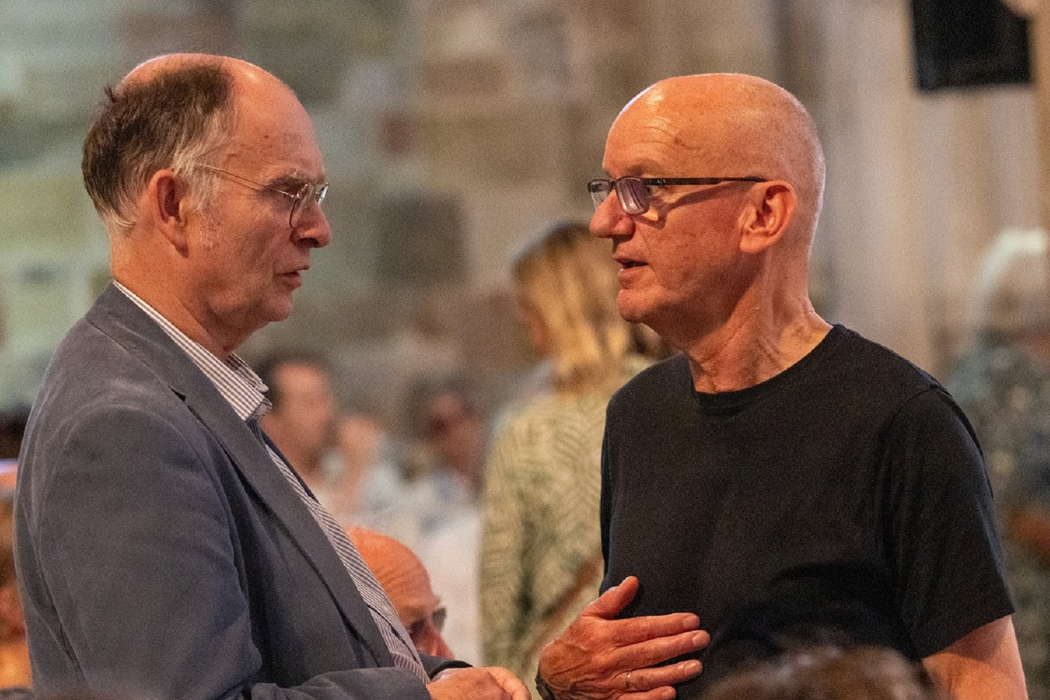

Adrian Partington meets up with the ever-inspiring and Three Choirs favourite Bob Chilcott. Photo © 2024 James O'Driscoll

It amounts to a magnificent collection from an immensely admired and justly popular composer. Chilcott is a special favourite of the Three Choirs, and with very good reason, as the present gripping work proved. (He will also feature next year.) The chosen subject of The Angry Planet is the fragility of our world, reflecting closely the Festival's theme this year, and the extensive text is by Charles Bennett, a poet of originality and distinction with whom Chilcott has successfully collaborated a number of times before.

The leitmotif of Bennett's extensive, exploratory text is wood, more precisely a forest, at night. The second sequence, 'When I woke it was midnight in the wood' is dramatic and angry: 'To grub the orchard up and rip the hedgerow out ... to hack the tree of England down, haul its root away and sell it for firewood'. And later, 'Chainsaws whine and howl as the forest dies ...'. However the poet's imagery stretches much wider: strange animals make an appearance, the ocean is 'smirched with oil', glaciers and ice-caps calve relentlessly, islands are wave-washed (by tsunamis?), falling snow, 'ditches and fallen fences'. The text offers much curious poetic licence: 'a horseshoe bat'; 'a loose-limbed otter lost himself in the water'; 'rolls and spills and ripples of fresh light'; 'our kisses will give you goosebumps'; 'corpses came from curbsides'; and a mournful list of sixteen threatened creatures: 'those who cannot speak for themselves'.

Chilcott brings to this testing, challenging text all his attractive compositional skills: many movements he preserves with a gorgeous pianissimo; there is a well-placed scherzo - in fact two, leaping and bouncing - that starts vividly and energetically then subsides unexpectedly and, paradoxically, beautifully. For 'Yellow Eye', from part one, Chilcott elicits a gorgeous, subtly crafted choral interweaving, sung here by a marvellously accomplished, and expressive three cathedral choirs under Samuel Hudson. The terrifically prepared youngsters especially impressed, but so did all voices, particularly appealing in the many passages which Chilcott sets pianissimo. He knows the importance of word repetition to amplify a text, and there is a fair amount of that.

Boy and girl choristers with soprano Florence Price perform together for Bob Chilcott's highly dramatic, bracing and powerful oratorio The Angry Planet.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

In short, Chilcott's oratorio, superlatively contrived, proved one of the undoubted highlights of the week. As indicated above, besides his splendid inventiveness in church anthems and carols, he has wrtten several full-length masterpieces. From this Three Choirs performance, it seems pretty certain that this is one of them. The accompanying commission from Paul Mealor - Ringed with the Azure World - including settings of Tennyson and a fresh treatment of the 'The Silver Swan', famous from Orlando Gibbons, proved yet another of those intensely successful short works prefacing several evening concerts.

Paul Mealor celebrated on his enraptured 2024 Three Choirs commission.

Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

Ian Venables' setting of the Requiem is, by any standards, a work of ravishing beauty. Every feature of it - the masterly way he employs just a handful of enchanting short phrases or motifs, beautifully related; the refined judgment he displays to elaborating every movement or section; the delicacy and intensity he brings to each evolving phrase; the wisdom with which he treats each line of the text, confirm the work as an undoubted masterpiece.

And on this occasion, his amazingly secure and mature approach to his orchestration, to judge by the rapturous applause following its performance throughout the cathedral, it seems that this work, perhaps above all, was a triumph for the (superbly polished) youthful choir, the members of the Philharmonia, and the composer.

Ian Venables. Photo © Simon Stafford

It was Venables' second breathtaking participation in the week's events. Midway, he offered a gorgeously and finely crafted setting of the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (Evening Canticles). He has in fact previously composed several enticing, indeed uplifting anthems. Each has the mark of his special command of word setting. Word setting is indeed his speciality. He is nationally, and increasingly internationally, famous for his very considerable number of acclaimed, arguably brilliant, song settings. They have drawn from him some dozen cycles, each in its way utterly inspiring. To say he is England's finest and easily most accomplished composer of Art Song is surely an understatement.

Since its premiere at Gloucester Cathedral (under Adrian Partington, who conducted here, and who actually founded this youth chorus, which he finessed from its very outset), Venables has orchestrated for the Requiem this breathtakingly beautiful version, wholly original, amazingly subdued, subtly poignant, treating that modest, compactly offset series of expressive motifs, the whole an example of remarkably evocative, often poignant setting of the contrasted passages of text. Venables', exquisitely crafted, deeply felt Requiem has been hailed everywhere as a masterpiece, and with good reason.

The Three Choirs Festival Youth Choir performs magnificently in Ian Venables' Requiem. Photo © 2024 Dale Hodgetts

To hear it here with the Philharmonia Orchestra felt, to put it mildly, all but a miracle. It was typically bold of Worcester's current festival to include it as a major item in this season's evening programme. And it paid wonderful dividends.

So much of the Requiem is finely subdued, and so perfectly refined. The opening Introit and the Kyries, for instance, are both profoundly reflective and utterly captivating thanks to the marvellous intimacy and restraint Venables brings to them both: the Kyries - with an entrancing start for female voices - are pleading and supplicatory; and both embrace (as the composer says) an impassioned climax; but the tenderness is revisited, with the exquisitely created melismatic idea (motif, or motto) greatly contributing, time and again, to the gorgeous calm of the whole.

By way of variety, it is the men's voices that attain prominence in the longer, dramatic, even 'anguished' Offertorium. The expression here alternates from forcefulnesss and urgency (a prayer 'de poenis inferni' - to set free from the pains of Hell), and the grim 'jaws of the lion - treated to a big, domineering passage - leaning into more optimistic, hopeful sequences ('We offer you sacrifices and prayers of praise'). Venables has aptly proposed the term 'Sturm und Drang' for this multifaceted movement. It fits.

Not surprisingly the intimately explored and repeated two lines of the Pie Jesu, which Venables decided to set only subsequently, as a form of memorial, is one of the Requiem's most expressive parts; not least because he has opted to set these moving words a cappella - without orchestra. The impact is mesmerising. Yet comparably beautiful is the Sanctus, drawing on another of his mottoes (descending like a kind of inverse), which again he presents pianissimo, with notable use of paired voices, the gentlest of organ parts, and delicately subtle instrumental touches. Like the Offertorium, the Agnus Dei starts with the men, the female voices later added above, and is one of the places where Venables' use of judicious repetition produces such an alluring, intensifying effect.

The Libera Me, again like the Offertorium, cries out for relief from the terrors of judgment and death. The tenors and basses - splendidly sung here - are again prominent, and skilfully conceived, and more or less trudging during the fiercely threatening Dies Irae. Yet despite its menacing, deep foreboding and even patches of dissonance quite a lot even of this movement is sung comparatively piano. And the effect - perhaps the irony - is all the greater. The inspired appearance in the final movement, the Lux Aeterna, of a solo oboe playing almost dazzlingly one of the salient motifs, just as a threatening, warning trumpet call or telling use of echo in the flutes during the Sanctus, exemplifies the ingenuity - indeed mastery - with which Venables has carried off the orchestration.

A few other items cry out for a mention: an accolade, rather. Cecilia McDowall's ingenious Shipping Forecast, with Worcester's Chairman, Ben Cooper, as a striking and forceful narrator, revealed the same night the deftness and inventiveness of the same composer's Antiphon Sequence we heard earlier in one of the organ recitals.

Cecilia McDowall. Photo © 2023 Karina Lyburn

There was a fascinating world premiere: a most remarkable Sonata pieced together - marvellously and with much love - by Jeremy Dibble out of movements from five of Stanford's string quartets, clearly proving the quality of Stanford's work in this field. Its range, Dibble, who clearly rates these works exceptionally highly, entails compelling fecundity, playfulness and wistfulness, a sense of passion, enthralling forward driving; compelling energy; tranquil and rhythmically becalming. All of these things he proved.

Plus on the Monday, under Samuel Hudson, as attractive, lulling and intelligently characterised a performance as one could imagine of Elgar's Serenade for Strings. Astonishing.

Next year it will be Hereford's turn, and among the unusual gems Geraint Bowen has planned are William Mathias' This Worldes Joie, a work previously championed by Roy Massey; Herbert Howells' intensely moving and to a degree biographical Hymnus Paradisi; Bliss's tender Mary of Magdala; a massive (ninety minute) and virtually never heard work by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, The Atonement; plus the world premiere - a festival commission - of The Black Lake by the versatile and engaging Richard Blackford; and more Bob Chilcott - his Mass in Time of War, another bracing commission. Clearly a veritable feast is in store in 2015.

Copyright © 26 August 2024

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK