- Digressione Music srl

- Connecticut

- Shostakovitch

- payments

- Dame Felicity Palmer

- Attilio Malachia Ariosti

- Chopin: Etude in E Op 10 No 3

- Seong-Jin Cho

Richly Coloured and Immediate

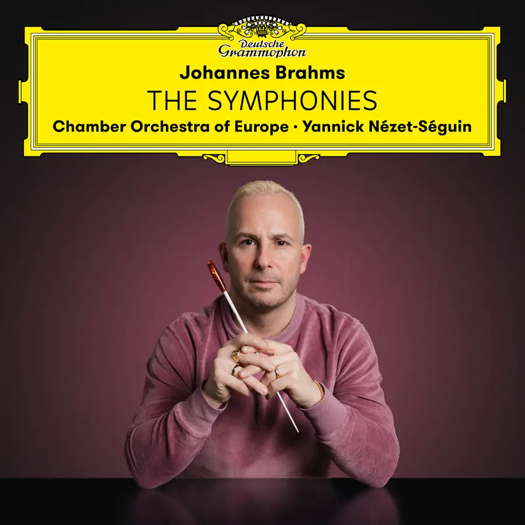

GERALD FENECH finds Yannick Nézet-Séguin's Brahms symphonies unmissable

'... performances of the greatest clarity ...'

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was one of the romantic period's most conflicted musical characters, and his four symphonies are the perfect way to find out why. Many think that Brahms was a quiet character but this image is proven to be a complete myth. Indeed, his symphonies give ample proof of all this, and few symphonic composers have done so much with so few works. Maybe this is the real reason why these four symphonies have lasted the test of time thanks to their verve, freedom and complexity. Still, Brahms' symphonic journey did not start off quite like that.

Symphony No 1 in C minor, Op 68 (1876)

If any one composer in history was hyped to breaking point, it has to be Brahms. For a variety of reasons, he was seen as the natural successor to Beethoven, whose legacy cast a long shadow over the nineteenth century. Basically, everyone was expecting Brahms to pull out the big guns and follow Beethoven's Ninth, but when the composer took twenty-one years to come up with his first symphonic utterance, expectations were sky high.

Listen — Brahms: Un poco sostenuto – Allegro (Symphony No 1 in C minor)

(DGG 4866000 track 1, 0:00-0:42) ℗ 2024 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

The premiere took place in Karlsruhe on 4 November 1876, under the baton of Felix Otto Dessoff, and the work was a huge success, although comparisons to Beethoven's Ninth did annoy Brahms, who later confided that his intention was not to be guilty of plagiarism but to compose a piece of conscious homage to the great master. This is the only one of Brahms' symphonies to use a formal introduction and the work also incorporates orchestral sonata form, a violin solo in the slow movement and a melody in the final movement inspired by an alpine shepherd's song, which in the finale is transformed into a blaze of incomparable beauty.

Listen — Brahms: Adagio - Più Andante - Allegro non troppo, ma con brio -

Più Allegro (Symphony No 1 in C minor)

(DGG 4866000 track 4, 5:25-6:08) ℗ 2024 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

Symphony No 2 in D, Op 73 (1877)

After the nightmare of expectation and hype that surrounded the first symphony, you might expect the second to contain some of Brahms' most melancholic work. Surprisingly, it is light and airy, resembling in character Beethoven's 'Pastoral'. It is a breeze to listen to, with the first movement especially full of sweeping melodies to whistle along with. In contrast to the time Brahms took to finish his first symphony, the second was finished in a single summer during a visit to Portschach am Worthersee, a lakeside resort town in Austria. The setting was apt for the work but moments of pastoral sparkle are occasionally perturbed by clouds. Indeed, during its composition Brahms dubbed the piece 'the lovely monstrosity'. On the contrary, the composer's friend Theodor Billroth described it as 'all blue sky, babbling of streams, sunshine and cool green shade.' Well, both assessments contain a bit of truth, but with its peaceful melodies, mischievous dances and a terrific fourth movement that breathes fire all along, I am more inclined to fall in line with Billroth.

Listen — Brahms: Allegro con spirito (Symphony No 2 in D)

(DGG 4866000 track 8, 4:01-4:58) ℗ 2024 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

Symphony No 3 in F, Op 90 (1883)

After the heroism of the First and the pastoral flavours of the Second, the Third inhabits a more uncertain world. An unusual feature of this work is that all four movements end quietly, something unprecedented in symphonic literature of the time. Twenty-seven years after Schumann's death, Brahms pays affectionate homage to his one-time mentor and friend with a quotation from Schumann's Third (Rhenish) of 1850. The 'Allegro con brio' is rich in rhythmic invention, embracing a wide range of feeling from euphoria to melancholy. After a turbulent ride, the music comes to rest with a gentle reminder of the opening motto theme.

The clarinet led 'Andante' has its moments of serenity, although they do not conceal an undercurrent of regret. Near its end, however, the violins are given the chance to shine with an ecstatic crescendo of joy, before the coda is allowed to dissolve into silence.

Listen — Brahms: Andante (Symphony No 3 in F)

(DGG 4866000 track 10, 6:35-7:27) ℗ 2024 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

Perhaps the tenderly nostalgic 'Poco allegretto' that follows is a song of farewell to Schumann's widow Clara, the love that had once consumed the young Brahms for his friend and muse having never completely faded. The 'finale' is a tour-de-force of changing moods and rhythmic twists, and what feels like the prospect of a triumphant ending eventually comes full circle, ending with a soft echo of the opening bars.

Symphony No 4 in E minor, Op 98 (1885)

The Fourth Symphony is, to all intents and purposes, Brahms' crowning symphonic glory. This work is the only one of Brahms' symphonic canon to end in a minor key - a rarity for a symphony of this period. It is considered the darkest and most tragic. Technically deeply complicated while remaining exacting and succinct at the phrasal level, many critics consider it the pinnacle of Brahms' symphonic achievements. The composer himself worried about how the work would be received, but despite some criticism, the piece was welcomed for what it is, and the Fourth remains well-loved and often performed to this day. Dense and intricate, the Fourth Symphony is ripe for repeated listening, and although it harks back to Beethoven, Schumann and Bach, there is so much to discover. Indeed, critic Edward Hanslick summed it all up when he said:

It is like a dark well, the longer we look at it, the more brightly the stars shine back.

Listen — Brahms: Allegro giocoso (Symphony No 4 in E minor)

(DGG 4866000 track 15, 4:57-5:55) ℗ 2024 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH :

Cycles of these great masterpieces are certainly not at a premium and the choice is rich and vast, but in most of these the symphonies are performed by a full-sized orchestra, something that Brahms did not agree with. Indeed, the First Symphony was premiered in Karlsruhe by only forty-nine players and the Fourth, premiered by the Meiningen Court Orchestra, was only performed by forty-eight players. Strangely enough, it has transpired that when these pieces are performed by a smaller than usual orchestra the music is revealed with greater transparency by using fewer strings.

Yannick Nézet-Séguin draws performances of the greatest clarity, and while adhering to Brahms' wish of a reduced orchestra, he never fails to stamp his authority on the flow of the music, which is always richly coloured and immediate. Nézet-Séguin has some truly stiff competition in the likes of Karajan, Klemperer, Bernstein, Solti and a host of other big names, but this cycle is no less a revelation in its warmth and delectable airy charm. A gem of a set that should be part of any collection. Unmissable.

Copyright © 14 August 2024

Gerald Fenech,

Gzira, Malta