UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

UPDATES: There's a new feature every day at Classical Music Daily. Read about the various ways we can keep in touch with you about what's happening here.

To Vladivostok With Thanks

Memories of the Russian pianist and teacher Vadim Suchanov (1949-2024) from BÉLA HARTMANN

These recollections of my former piano teacher come from a desire to mark his departure with a sense of gratitude and respect. In spite of my time studying with him and subsequent enquiries about him I have very little knowledge of the hard facts of his life. This is partly due to his life as an emigre, far away from what family he had, and partly to the erratic nature of many of his relationships. I assume his parents are no longer alive, but I also know he had a brother and nephew in Moscow with whom contact seemed to have been lost in his later years. Therefore, if these recollections are inaccurate in any way I would be grateful for corrections, and if they view things very much from my personal perspective it is from the lack of other perspectives to draw on.

Vadim Suchanov was a highly respected Russian pianist and teacher, born in Vladivostok in 1949, who after leaving Moscow around 1980 was for most of his life based in Munich. He recently passed away in complete obscurity after withdrawing into a life of little contact with others, but is and will be remembered with great warmth and appreciation by countless colleagues, pupils and friends. For several years in my teens he was my teacher, and the fact that I now enjoy life as a professional pianist is almost exclusively due to his inspiration and skill; amongst his pupils there are many successful pianists and prizewinners of international competitions. His was a complex character, full of warmth and generosity on the one side but prone to alienate even close friends on the other, so his death in conditions of almost complete solitude saddened but did not surprise many of his past acquaintances. Yet he brought so much good to many aspiring pianists and was held in such esteem by many much more celebrated musicians that it seems unthinkable that he should just slip away from near to complete anonymity with only private appreciation on the part of one or two dozen former pupils to accompany him.

I met Dima, as I was encouraged to call him, through the mercurial Cypriot pianist Nicolas Economou, whom I had approached during the ARD Competition in Munich asking for a chance to play to him. Nicolas agreed, listened to my playing some days later and agreed to take me on, adding however that he wasn't really a teacher and therefore would recommend I also have regular lessons with his friend Dima Suchanov. I began visiting Nicolas several times a week, dropping by his apartment after school, and there met Dima, who indicated he would be happy to follow this plan. At the time he was teaching at the Richard-Strauss-Konservatorium in Munich, a slightly lower-rated municipal sibling to the more glamorous Hochschule für Musik. Apparently he had found this position through Russian colleagues after emigrating. It was quite a new building, part of the Philharmonie am Gasteig complex which also housed the municipal library where I spent many hours sifting through sheet music and listening to rare LPs and cassettes that couldn't be taken out. It was a brick building, fairly dark inside but well heated, usually busy with students and other people using the various facilities in the complex. Apart from the large Philharmonie the building included the smaller Carl-Orff-Saal and the very small Kleiner Saal which accommodated the bulk of the student concerts.

Dima taught in a smallish room with two grand pianos, mostly spending the lesson sitting at one of them or wandering around. Being only fifteen years old at the time I was still at school and was only coming as a private pupil. I would arrive early and sit in on the tail end of the previous pupil, usually a female student who for a while was working on Schumann's Davidsbündlertänze. Dima could be a fearsome teacher: he would often shout and frequently became very impatient - one had to develop a thick skin to get through it. Tears from the pupils where not uncommon. He had many ways of telling a pupil they weren't playing well, some very imaginative, some very colourful. I recall a lesson where he was more than usually cross with splashes and wrong notes in the Chopin Etude I was playing. He shouted repeatedly, more and more angrily. Needless to say I played with more and more caution until he accused me of playing without pleasure - so boring! he said. However fierce he could be he was also able to praise and give you the feeling you could do it. I remember the feeling of confidence I would have when he signed off on something. You felt you were ready to play! He always gave me the feeling he truly believed I had talent and could do something special. The ferocity of his criticism and the level of detail he demanded in turn made his praise immensely powerful.

The levels of detail into which he delved were completely new to me, as were the demands in terms of learning and absorbing: if I had a new piece I was expected to learn it quickly and from memory in a week or two to give time for useful work in the lesson: Dima was not interested in being dragged through a piece in its early stages. He was not one for preparing everything, noting fingerings etc. He demanded I sort it out, and then he would make amendments as he saw fit. When early on I started noting fingerings or other instructions in my copy he immediately told me to stop. That was a silly habit, he said - I should keep these things in my head. This meant I had to become quite independent in learning material, much more so than I had imagined before. From his stories about his own time studying I got the distinct impression that he had never been one to whom technical mastery had come easily, rather that he had had to work hard to find solutions to problems, experimenting with fingerings, often rearranging things between the hands. This inventiveness suited me very well as I had come late to this level of playing and had many deficiencies in my technique: I needed an imaginative approach to help me get through the many unaccustomed challenges I was facing. Dima was quite discerning in what alterations he would suggest or allow. I remember redistributing a passage in a Chopin Scherzo to his displeasure: he said Chopin had been an excellent pianist and probably had a reason for his distribution. However, these subtleties had little consistency. On another day he recommended differently. You couldn't really accuse Dima of excessive consistency, or of being too methodical. However, the same can be said of most great piano works, so whilst this approach was confusing and unpredictable it was also flexible and creative. It taught me that one should approach each thing on its own merit. And that merit can change.

He would spend much time in the lesson practising with me and demonstrating at the other piano, repeating small phrases again and again, trying to give me more awareness of legato, balance, tone etc. It was this process that stuck with me most: practising together, showing a phrase, listening to my attempt, repeating, listening, repeating again and again until either he gave up or I got it. When he demonstrated he played with the most beautiful sound I can remember. Not beautiful sound in the sense of colours, as my later teacher John Bingham always demanded. It was more the transparency of the sound, the perfect balance of all the elements, as if many different instruments were playing in a perfectly attuned ensemble. As much as any other element of his teaching this ability to judge and voice harmonies stayed in my memory and has always been something I have aspired to in my own playing. He rarely spoke about tone colours, only when he felt something specific was going wrong, but so much of his teaching seemed to imply a strong emphasis on tone, always through his demonstrations. As Dima himself, although an excellent pianist, was never a typical Soviet virtuoso and eschewed the more steely sounds, he played with a certain gentleness, perhaps most akin to Emil Gilels in his more intimate moments, or even more to Vladimir Sofronitzky. Dima was also a strong believer in the importance of a more general cultural awareness for being a musician. Whether it was other areas of music he encouraged me to explore, or novels by Stendhal or Tolstoi, or paintings by Masaccio, he opened many vistas to me that remain central to my life today. To me he represented an entirely consistent approach to music, one that I could identify with and that harmonized with my own personality, and when he surprised me, as he often did, by suddenly espousing or praising something I hadn't thought of as being part of that approach I took it especially seriously.

As a musician Dima had a modest but tangible career. He had won some important international prizes as a young pianist - Prague Spring, Geza Anda Competition in Zürich - and kept a regular run of concerts going in the time I knew him, albeit a small one. I especially remember a wonderful recital he gave in the Musikhochschule that featured Schubert's 'Der Müller und der Bach' and 'Erlkönig' in Liszt's arrangements, the 'Wanderer' Fantasy, then in the second half Schumann's 'Winterzeit 1&2' from the Album for the Young and the Symphonic Etudes. It was a great concert: I remember especially the long pause before the Finale of the Etudes which seemed to separate it from the Variations - a small touch but one which literally took my breath away.

Another recital some years later gave an idea of why he hadn't built up more concerts. He had been very close to many Russian emigres and musicians in Germany and was especially close to Natalia Gutman and her husband the violinist Oleg Kagan, who at that time was dying of cancer in a Munich hospital. Dima had been spending a lot of time with Kagan in his last days and hadn't touched the piano for some time, yet was due to give a recital in Augsburg which was to be broadcast by Bavarian Radio. I attended the recital and much enjoyed it - if I remember correctly it included Chopin's Polonaise Fantasy, Scriabin's Sonata No 5 and Chopin's Sonata No 3. A hefty programme which he played with characteristic colour and imagination, but which did include a fair number of accidents and memory lapses. But his concerts went on for many years and he even gave a recital for Mikhail Gorbachev on the occasion of a state visit. He was also occasionally invited to give masterclasses, and for a while travelled to Seoul every now and again to teach. He told me he felt comfortable there as it was so close to Vladivostok.

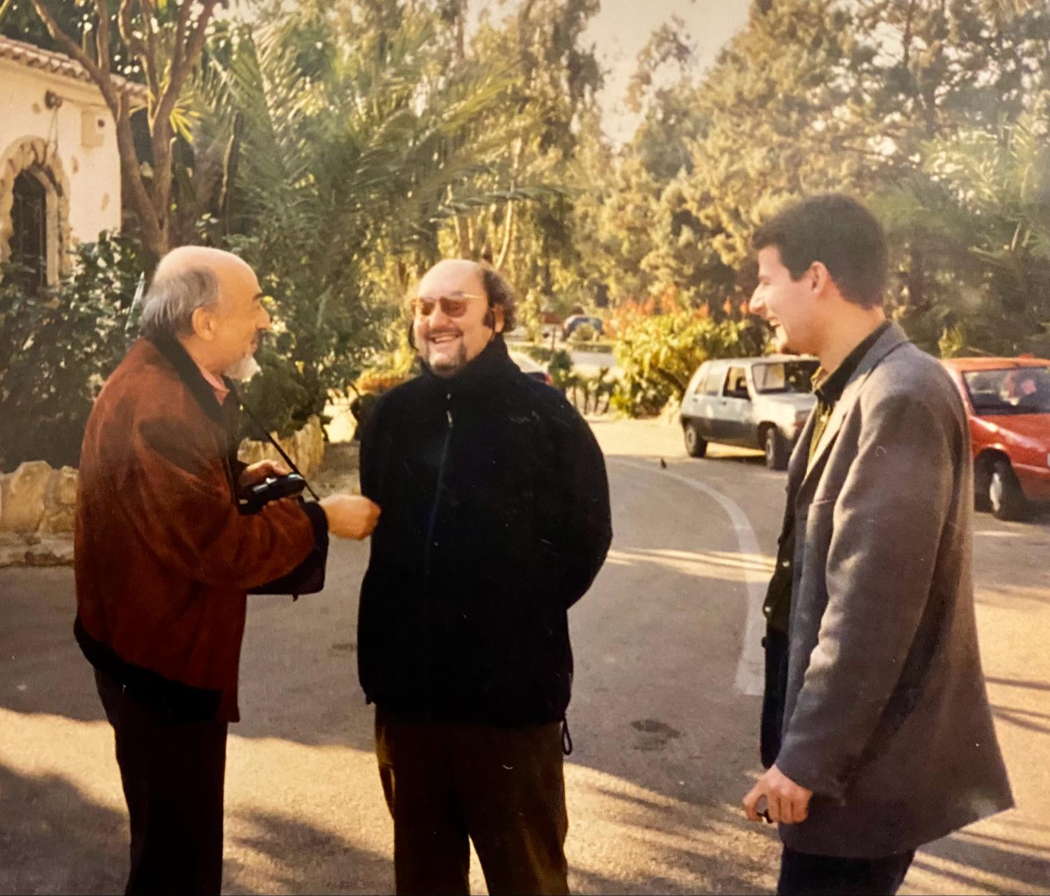

Dima often recounted stories from his time in Moscow, but they were anecdotes which I could in no way verify. He seemed to have been held in high regard by the crème de la crème of Russia's musicians: he was a close family friend of Shostakovich and Shostakovich's son Maxim, even taught the grandson Dmitri Jnr. He was good friends with Gilels but also on friendly neighbourly terms with Sviatoslav Richter. He was befriended by David Oistrakh. However, when he told stories of his time studying he was less warm. After his time at the Central School he moved up to the Conservatoire where his teacher became Jakub Flier, and whose assistant he briefly became. My impression was that he struggled a little bit against the more high flying students and felt that what he had to offer was not valued as much. He was later taught by Dmitri Bashkirov and became his assistant in a relationship that seemed more harmonious and which was to last well into my days when Bashkirov would regularly send his own pupils from Madrid to work with Dima in Munich.

Dmitri Bashkirov (left) with Vadim Suchanov and Claudio Carbó Montaner.

Photo © Claudio Carbó Montaner

A further deep influence of Dima on my musical journey was his general musical outlook. I was a young music student very much in the mould of Berlioz - opinionated and constantly attacking and condemning some celebrated pianists whilst praising others to the skies, and in this vein Dima was if not encouraging then at least supportive. His opinions of others could be harsh beyond words but equally he could be full of praise where one might least expect it. As my own tendency to be judgemental gradually calmed down I was left with the undeniable insight that being famous does not mean you are good, or that being obscure does not mean you can't be valuable.

Dima was full of surprising comments ('Horowitz never managed to play the 3rd Scherzo [Chopin] properly') and his often unpredictable reviews would mean I was constantly forced to question what I had settled on in my mind, which can never be a bad thing. He transferred his deep love of Schubert onto me, and my life-long fascination with the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler was a direct result of Dima's comments. He always enjoyed performances that made you reevaluate the music, that even made the work in question difficult to recognize. When he had recorded a CD of the Brahms Second Piano Sonata with his old friend Valery Afanassiev he was initially dismayed that soon afterwards a similar CD was released by Martha Argerich, another close friend of his, and her then partner Alexandre Rabinovich, in which the same work was played, not untypically for Martha, faster and more excitingly. He then calmed down and declared seriously, and I believe he was serious, that there is value in a kind of 'noble boredom', that to be exciting is not always the best thing for music.

Valery Afanassiev (left) with Vadim Suchanov

My studies with Dima came to a natural end when I took part in the Montreal Piano Competition, severely unprepared. He had been getting edgy about it as it became clear I wasn't going to be ready, but when I insisted I still wanted to go he told me to go away and stay away. As a teacher myself now I quite understand his approach, but at the time it was a shock. In truth it was probably a natural process as I had felt a distinct cooling of relations for a while.

I had some time previously played to John Bingham in London, who had indicated he would be happy to teach me, but that was just as I had begun with Dima, so nothing came of it. A hurried audition later and I was enrolled at Trinity College in London in a vastly different musical environment. After a year or two of silence I wrote to Dima to apologize and to express my gratitude for all he had done for me, to which he responded warmly and even visited me in London. When my time there was coming to a close he suggested that I play to Elisso Virsaladse who was just building up a class at the Hochschule in Munich, with a view to taking up a postgraduate course with her. Through his friendship with her she accepted me as a student and a new chapter began for me, one that brought Dima and me closer again.

Virssaladse spent around a week every month in Munich at which point her students, who lived scattered across wider Europe, would congregate for daily lessons with her. I had successfully applied for a grant from the Tillett Trust to help me with travel expenses but still needed somewhere to stay in Munich for those times, and Dima offered to put me up in his house. So, for a year or two we spent a week every month together and I got an insight into his private life, something I hadn't been exposed to as a teenager. He was a most generous host and shared all he had with me. I had a room upstairs but spent most of the time downstairs with him or practising on his piano. Cooking for Dima at the time meant instant noodles with added spices, and drinking was several bottles of beer, then wine, then spirits, every night. We spent the evenings chatting and listening to music in a state of increasing inebriation. Dima was not a born housekeeper: the house was usually in a terrible mess and I spent some time every stay cleaning up a bit, cooking some decent food or just tidying. He didn't really wash his clothes, just wore them until they were smelly and then threw them in a dedicated room upstairs where they would lie around indefinitely. Every now and again he would go out to buy new clothes, so gradually there was a mountain of dirty laundry heaped up in a room best avoided. In the summer Dima's mother would come to visit from Vladivostok. She was a very cheerful lady, and she would spend the whole visit cleaning and washing - the overgrown garden was full of washed laundry drying off a dense mesh of clothes lines. I wasn't usually around in that time as it tended to be during the summer holidays, but when I was she was very friendly to me. I couldn't tell how the two of them got on but they seemed harmonious, at least on the surface.

Occasionally Dima practised himself, preparing for a concert - at the time he was working with Natalia Gutman. I particularly remember him working on the C Minor Trio by Brahms. I didn't know it before then and became captivated. It sounded such a magnificent piece, so full of amazing harmonic shifts, syncopations and beautiful phrases. It has never sounded so good to me since, I searched out many recordings to listen when I returned home, but could never understand why it seemed so much less interesting than I remembered. Occasionally he commented on my playing when I practised, but largely he kept quiet, out of respect for Virssaladse.

Frequently Dima would drop in on the lessons Elisso was giving at the Hochschule. He would listen a bit and then accompany her to lunch or supper. On these occasions he was very remote toward me, presumably not to mix his relationship with her with ours. It took me a while to get used to his sudden aloofness, but I did understand. In spite of his rather chaotic lifestyle he seemed to be a stickler for certain formalities, especially in relationships. He would have no compunction in ceasing relations with someone he felt had not shown enough respect, even by being late to call, or by calling without getting his number from a bona fide source. I witnessed him on several occasions turning down promising possible pupils because they hadn't been recommended properly, or hadn't gone through the proper process to enquire. Whether they had any idea what this process was didn't matter. At home Dima used an answering machine for his telephone - not a universal practice at the time in Germany. He would screen every call before picking up, deciding carefully whether he felt inclined to speak, or whether this person deserved a conversation. I found that very unsettling, as of course every time I called and spoke on the machine I had no idea whether he was there weighing up his options or was in fact away.

Perhaps due to alcohol he could be very moody and changeable in his attitudes toward others and frequently spoke badly about his acquaintances. Looking back now I imagine he was suffering from depression exacerbated by drink. He was very aware that he was a much better musician and teacher than his reality reflected, but seemed equally insecure about his playing in comparison to others, mostly in terms of technical resources. He realised gratefully how many of his more celebrated friends tried to help him, by playing with him, such as Gutman, Afanassiev or Virssaladse, or by sending him good pupils, such as Bashkirov. He was never resentful about what he saw as his more capable friends: he admired the talents he saw in others but not in himself, and never showed any hint of bitterness. Indeed, he often said of one or the other pupils of their playing that he himself couldn't do as well. There was a lot of good will toward him that helped him temporarily but didn't change anything in the longer term.

I believe - without any hard knowledge to back it up - that Dima was left scarred by a certain insecurity dating from his studies in Moscow and by the feeling that his emigration had fatally compromised what could have become a much more substantial career, never mind a more natural personal life. By the fall of communism it was too late, he had become estranged from Russia and couldn't contemplate returning for more than an occasional visit. In this respect there were probably many other emigres in a similar quandary. The final blow was struck when the Richard-Strauss-Konservatorium was incorporated into the Musikhochschule: some professors of the RSK became professors of the Hochschule, but Dima was overlooked and was left to teach second study pianists and ensembles. Presumably he hadn't done the necessary negotiating or positioning to persuade the authorities he would be useful to first study pianists. Apart from being an act of colossal stupidity on the part of the Hochschule it finally convinced Dima that there wasn't anything left for him. From then on he withdrew completely into a life of isolation with only a tiny number of friends to communicate with.

There are many people, musicians, music lovers or just people who came into contact with Dima, who will have warm and appreciative memories of him and who will be saddened by his death and the isolation in which it came to him. Other than lashing out figuratively or just cutting ties with people I don't know of any grievances held against him - I have never come across any other suggestions of wrong-doing that are common in the world of classical music and its education, such as vanity, manipulation, corruption or sexism. In that sense I believe Dima was a highly decent character with a strong sense of integrity, only with a deep sense of unease at his place in the world and the nature of his relationships with those around him. When in 1989 I telephoned to tell him Horowitz had died, his response was 'Good for him - now he doesn't have to put up with all this terrible world any more'. I hope Dima is at peace now, safe from this terrible world, and aware how much admiration and warmth this terrible world had for him.

Some sketches of memorable moments with Dima:

- A magical evening in our flat with Dima and the passionate communist Nicolas Economou drinking vodka and together with my Czech emigre mother singing old communist songs. Dima never spoke much about politics except the usual observations on corruption etc. I have no recollections at all that would indicate where he stood politically.

- Visiting Munich Zoo with Dima. We arrived at the lion compound just as one bored looking lion climbed onto a bored looking lioness to mate. Dima declared: 'How wonderful, they waited for us.'

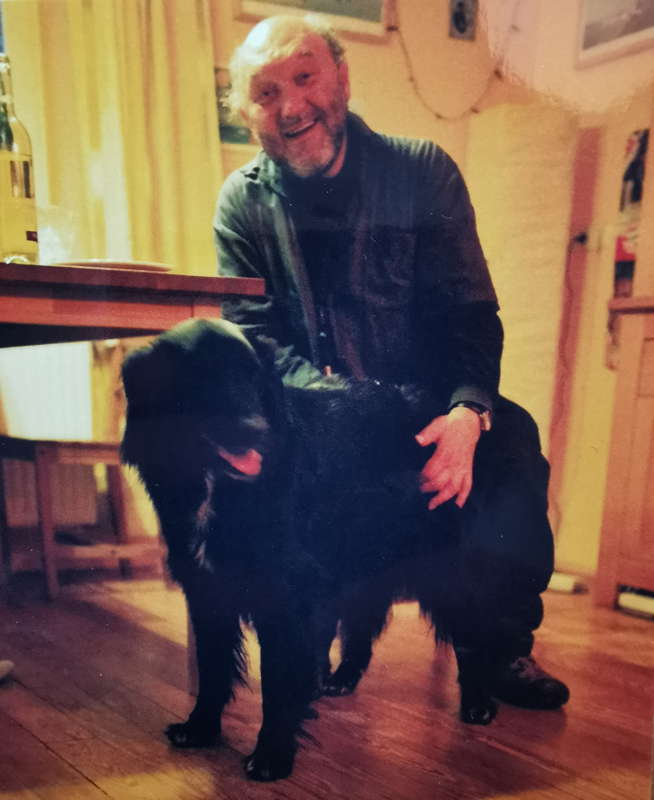

Vadim Suchanov (1949-2024). Photo © Olga Salogina

- Cycling together through forests close to Dima's house. In a rather random way he could be quite health conscious.

- Listening to old recordings in his house. In those days of LPs historical recordings were much harder to access and their existence harder to learn about. Hearing Bartók play Scarlatti, or Egon Petri play Schubert/Liszt songs was a revelation only increased by the addition of Dima's unpredictable comments.

- Listening to Dima's stories of life in Moscow and the musicians he knew. His meetings with Maria Yudina, his descriptions of Oistrakh, his tales of listening through the thin walls separating their apartments to Richter endlessly practising Schumann's Symphonic Etudes, of students competing against each other at sight reading and Radu Lupu being able to sight read upside-down scores. Of Shostakovich's generosity, of being groomed to marry Gilels' daughter Elena. Of Dmitri Alexeev being told off when playing through his competition programme in Bashkirov's class after winning Leeds.

- Taking him around London when he visited me after I began studying at Trinity College.

- Participating in his strange diet of Chinese noodles soaked in the kettle in freshly boiled water and then spiced with various MSG-rich herb mixtures. After a few days of this I felt decidedly peculiar.

Copyright © 8 April 2024

Béla Hartmann,

Surrey, UK