WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

WORD SEARCH: Can you solve Allan Rae's classical music word search puzzles? We're currently publishing one per month.

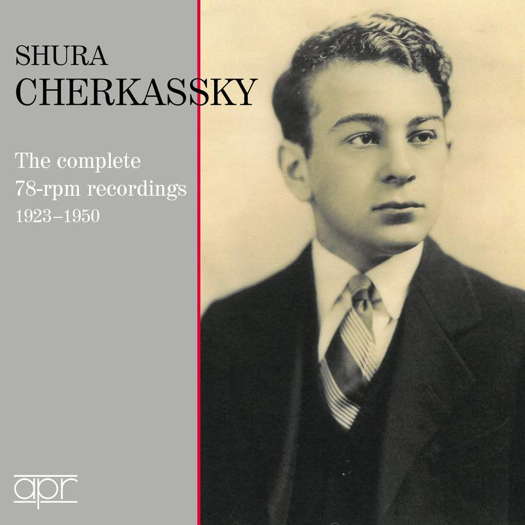

A Romantic Piano Master

ESDRAS MUGATIK listens to Shura Cherkassky

'... a magical capacity to differentiate levels of sound ...'

Shura Cherkassky had an unusually long career as a pianist. Born in 1909 he was still performing into the 1990s - and indeed probably until his dying day. He was one of those to go with his boots on, as they say in the Wild West. His connection with the nineteenth century piano tradition begins with his birthplace: Odessa. Something about the air in the city engenders pianists.

Secondly, he studied with Josef Hofmann who himself was a student of the great pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein. Hofmann is often considered one of the greatest pianists of all time. This lineage ought then to place Cherkassky in the succession of great Romantic Russian pianists. And it certainly does, though Soviet era pianists seemed to have taken a steelier turn in the 1920s and 30s and of course, much more, much later.

However, it is always somewhat peculiar to discuss these lineages. Hofmann was sometimes considered a modernist and Busoni came to his defence on such counts. But more important is that Cherkassky lived long in America with its characteristic sound world, culture and speech patterns. It would be wise to take these into consideration when trying to 'place' a pianist in this or that tradition.

Probably though, it would be best to just listen. On this new and wonderful three disc CD compilation lovingly and professionally restored are recordings from the first half (or so) of Cherkassky's life. They are mostly musical trifles and from the compositions alone one might develop musico-diabetic afflictions due to over-sweetness. There are some exceptions, but it is sad that more serious repertoire was not recorded. We can be glad for what we do have, but we must beware of ignoring what was lost, for we have a distorted picture.

For this selection will harden the incorrect notion that Cherkassky was a miniaturist, or worse, a small scale pianist. In fact, such was the opinion of him for much of his career. He seemed to struggle with receiving proper respect for his talent and achievement.

Indeed, his repertoire was very large and he kept adding to it throughout his life. He even added Stockhausen to his repertoire late in his career.

Now, what do we hear on these recordings?

Listen — Mendelssohn: Prelude Op 35 No 1

(APR 7316 CD1 track 2, 0:01-0:41)

℗ 2023 Appian Publications and Recordings Ltd :

We hear a magical capacity to differentiate levels of sound (and not by mere accentuation): melody, accompaniment and supporting bass tone. His command of this truly nineteenth century approach is astounding. The result is spellbinding. Modern listeners and pianists are probably mostly immune to this, having grown up with Phil Spector's 'Wall of Sound' audio engineering sonic ideal.

Next, we might say 'It's all in the pronunciation'. Cherkassky's music is sung 'as if he knew the words' and inflected with variety that sometimes bends the rhythmic shape, but almost always gives it life and certainly gives it grace.

Cherkassky was born before pianists were imprisoned in the bar line and the recording studio. That makes him a Romantic. Further, he served his own artistic vision, not that of reviewers, nor producers. The exception to this might be the Cello Sonata of Rachmaninoff in which a piano concerto is wedded to a sad sack cello part overwhelmed by its matrimonial partner. How did this piece come to be recorded? Sad, for the performance is very fine, the cellist (Marcel Hubert) noble in his efforts and the sound quite remarkable for its day. Cherkassky mastered the music and proves himself also a fine chamber music partner.

To me the least successful performances, perhaps because I had high expectations, are the Liszt Hungarian Rhapsodies (5, 6, 11 and 15). Some of the tone creations in the fifth (which is a pseudo Wagnerian Tristan-esque lament) are lovely, but the work does not jell. Horowitz's version of the sixth has deep six-ed everyone else.

Perhaps the most important recording here is of the Chopin Fantasy. Important because it is a certifiable great work of Chopin's, Cherkassky would seem ideally suited to this Romantic repertoire and because it contains so many elements that might reveal Cherkassky's pianism. Indeed, it does. First, the performance reveals the remarkable variety of tonal shadings - 'orchestral' in old style parlance - that Cherkassky had at hand and in imagination. Second, it reveals a technique that can produce the most vivid and extreme finger dexterity and chordal power. Third, is the elocution of the music where Cherkassky subtly accents, delay or anticipates with beautiful effect. The result is a performance that will gratify the antiquarians and the appreciators of old school pianism.

Listen — Chopin: Fantasy Op 49

(APR 7316 CD3 track 7, 0:00-0:56)

℗ 2023 Appian Publications and Recordings Ltd :

Some performances come as a surprise. The Saint-Saëns Prelude and Fugue Op 52 No 3 is (are) given a driven performance which does not let up, surging to the final bars in a torrent of virtuosity.

Prokofiev's Suggestion diabolique is given a rendition that is shy on the expected harsh sounds and yet works for its manner. I prefer it to the sonic battering Prokofiev usually engenders among pianists.

Listen — Prokofiev: Suggestion diabolique Op 4 No 4

(APR 7316 CD2 track 7, 0:00-0:50)

℗ 2023 Appian Publications and Recordings Ltd :

Was Cherkassky 'the last of the Romantics'? There are some other pianists who also take (or are given) that title. Any pianist who can manipulate three (or more) simultaneous sonic lines, any pianist who is his/her/their own judge and creative arbiter, any pianist who believes that Western classical music is important and in a way crucial (sacred?), any such a pianist should earn and deserve the title of Romantic. Who shall be the 'last' is another matter ...

I will end on a personal note. I heard Cherkassky play a concert in the mid 1980s and it included a fabulous performance of Beethoven's 'Waldstein' Sonata. Afterwards in the foyer leading away from the magical music making a prominent pianist from the town announced with Stentorian apoplexy: 'That was not Beethoven!' How that pianist knew so vociferously and emphatically what Beethoven was or is supposed to be I am not sure. Indeed, it was Cherkassky's very own interpretation of Beethoven and it was astounding. That's all that was needed.

Copyright © 9 February 2024

Esdras Mugatik,

Bradwardine, Manitoba, Canada