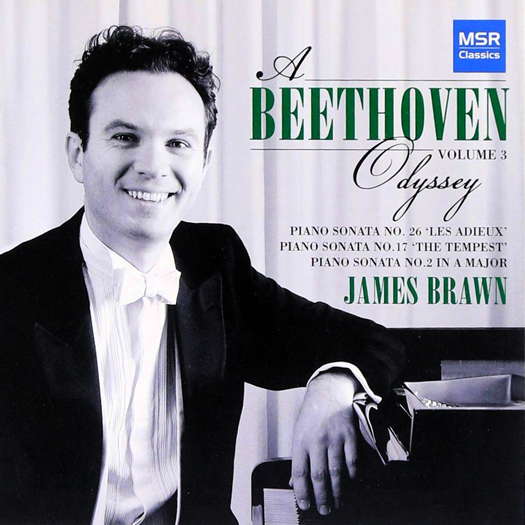

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

Per Giuseppe

Classical music, at least until it started to develop in new directions in the New World and beyond, has been one of the most extraordinary and overt manifestations of Pan-European history. For me, as a European, I doubt if there is any more impassioned, enlightening and enriching means by which to get to grips with the immense and fascinating richness - across space and through time - of the motley tapestry of peoples, customs, climates, languages, landscapes, faiths, philosophical ideas, artistic means of expression and experiments in living and dying that we call Europe, than classical music and vice versa.

As such, in this age of online magazines, blogs and forums where everybody seems to think their opinion is worth reading, it is extremely disappointing and saddening to encounter so much writing about classical music in English that is extremely ignorant of and/or indifferent - and what's worse blithely so – to this very same incredible motley tapestry. I am reminded of an anecdote of George Steiner's about how an eminent colleague of his from Cambridge asked him perplexedly 'What have concentration camps got to do with English Literature?'

This being the case one of the most attractive aspects of Classical Music Daily for me - and why I was very happy to have anything I write welcomed here - is the fact that it isn't yet another Anglocentric smug exercise in navel-gazing. Not another members' bar in a male only monoglot golf club. Although the medium here is obviously English, there are contributors here who are mercifully and gratefully from outside the English-speaking world. I wish there were more and I wish there were more women but beggars can't be choosers, unless you are Smokey Robinson. Contributors who have a perspective on music - and more - from outside the English language, ie the same perspective as the vast majority of composers and musicians who have made classical music what it is over the centuries.

There was no greater example of this here for me than our recently departed and very sadly missed colleague Giuseppe Pennisi. When it came to writing about classical music Giuseppe set the bar very high, as it should be. I felt proud to have anything I wrote published alongside his wonderful concert and CD reviews. Giuseppe, writing in his second or maybe third language, wrote better English than most native speakers.

Giuseppe Pennisi (1942-2023)

What I most appreciated and enjoyed in his writing was the sense that there was a real person behind everything he wrote. His reviews were not the clichéd cut and paste Wikipedia articles, such as so-and-so was born in ..., blah, blah, blah, nor written in a formulaic writing style which is so tediously predictable and prevalent these days. His erudition came from his extraordinary memory and his long personal and enamoured experience and not from some search engine and most valuable of all he gave his opinions - positive and negative - and explained why he held them.

I never met Giuseppe in the flesh but through his writing, I feel I obtained a very real sense of the man and the music lover. Giuseppe's reflections on his own rich recollections in connection with his lifelong passion for music and musical performance gave his writing a unique dimension. What made his reviews so worth reading and such a pleasure was that they were written by him and couldn't have been written by anyone else. Which for me is the very essence of criticism. As an example just read his magisterial review of Busoni's Doktor Faust published on 14 February last. If Busoni ever received a better Valentine's gift he was a very lucky man.

One last thing I want to mention that I really valued about Giuseppe and his writing is that, unlike so many people who pontificate about music these days, he saw classical music for what it is; an ongoing adventure, a phenomenon that has always been an intimate expression of its times and mores, whether that be the fifteenth century court of Burgundy, Lutheran Saxony, Belle Époque Paris, an early twentieth century reeling from the death of God and the reality of uncertainty, relativity and evolution, Nazi Germany or post-pandemic Putin-stalked Europe and not merely some simple feel-good after-dinner tuneful entertainment that died with Puccini or Mahler. He did not go in for the tedious and tiresome bigotry and idiocy that holds wonderful composers like Schoenberg or Boulez up as malevolent figures whose effigies need to be burnt in public in order to save 'real' music. Giuseppe, thankfully, as a man of his times and true to them and not one cowardly and ignorantly ensconced in some invented self-indulgent past, was as comfortable and enthusiastic talking about Verdi as he was talking about Salvatore Sciarrino: a composer younger than himself, or in the case of his very last article published here, Thomas Adès: a composer very much younger than himself.

As a very small token of my appreciation of and gratitude to Giuseppe Pennisi today's pranzo musicale has a very distinct Italian flavour.

1: Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924):

Berceuse Élégiaque (1909)

Busoni: Berceuse Élégiaque; Canto della Ronda degli Spiriti; Lustspielouvertüre; Four Songs for Baritone and Piano; Violin Concerto in D Major; Rondò Arlecchinesco - Boult, Fischer-Dieskau, Barenboim, Copland

Giuseppe left us on Easter Saturday. Ferruccio Busoni was born on Easter Sunday which in 1866 just happened also to be April Fool's Day. This piece was originally composed for piano in the summer of 1909 but when his mother Anna died that October he adapted it into this quite extraordinary orchestral lullaby. It received its world premiere performance under Gustav Mahler in what would be Mahler's last ever concert before he died three months later. It was also beautifully arranged for a chamber ensemble of nine instruments by Schoenberg some years later. Busoni believed that in this piece he had dissolved form into feeling. It is a magical molten example of how consonance and dissonance can be used and fused together to increase expressive possibilities. The orchestration is so accomplished and unique that even Richard Strauss was left in awe and in the dark as to how Busoni had produced some of his colours, especially what he called 'that whispered roar' that ends the piece. Today it serves as an elegy for Giuseppe.

2: Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-75):

Ulisse (1968)

Dallapiccola: Ulisse. © 2003 Naïve

Giuseppe ended his Doktor Faust review with a plea for a long overdue restaging in Florence of this twentieth century Italian opera. I still vividly remember my suppressed joy when I unexpectedly found this recording in the public library - or Mediateka as it was called there – in Bilbao many years ago. In many ways this work is a summation of Luigi Dallapiccola as man and musician. Unlike Homer's Odysseus who seems to have an answer for everything Ulisse seems to have more in common with Joyce's Bloom with his ceaseless questioning and as a twentieth century work I suppose that isn't surprising. However Dallapiccola's questioning especially about personal identity and the ultimate meaning of life has a philosophical emphasis all of its own. Chi sono? Che cerco? Ansioso cercare che giustifichi questa mia vita. Is this the fate of an artist in the modern age or just another self-obsessed man with a pathetically overblown sense of his own importance? All his interactions with others, especially women, seem to be mere means to the end of trying to know himself. He views himself as a stranger in this world until the surprising and unconvincing, for me, ending of the work. However like all great operas it makes one want to return to it as there is so much to explore, rethink and enjoy: multiple literary references, metaphysical ideas, the significance and presentation of the sea 'il mare rende saggi', its relationship to Schoenberg and his music. As he reveals to Calypso in his sleep 'guardare, meravigliarsi e tornar a guardare' is a motto that could serve for all artistic appreciation. To turn feeling into meaning as Robert Hughes once said.

3. Antonio Bibalo (1922-2008)

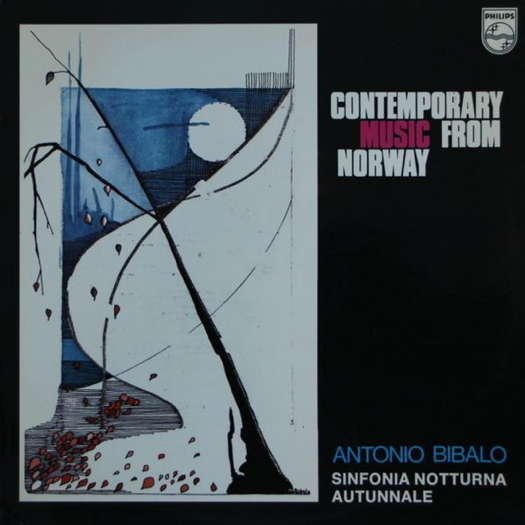

Sinfonia Notturna (1968)

Contemporary Music from Norway. Antonio Bibalo. Sinfonia Notturna Autunnale.

© 1972 Philips

All the genetic material of Joyce's Ulysses came from Dublin and although the book was born in Paris it was conceived and nourished in Trieste which is where Antonio Bibalo was born the same year Ulysses saw the light of day on a Parisian winter's morning. Bibalo like many Italians before and since spent most of his adult life outside of his homeland. His war-time experiences read like an all too real version of The Good Soldier Švejk although I imagine there was little of the comedy to be found in Jarolsav Hašek's masterpiece. Bibalo ended up in Norway of which he became a citizen in 1956. This rapturous orchestral ode to the 'eternal miracle' of night was inspired by lines of Norwegian poet Herman Wildenvey. Bibalo was also a passionate astronomer and in this piece he explores various facets of the night. From the distant cosmos to the melancholy depths of the lonely heart. From urban nightlife to the big sleep which awaits us all.

4: Franco Donatoni (1927-2000):

Hot (1989)

Hot. Ryan Muncy. © 2018 New Focus Recordings

Trying to choose one piece from the extraordinary menagerie of marvels that is the catalogue of Franco Donatoni's compositions is an onerous task indeed. So rich in invention, detail, colour, personality, effervescence, wit and magic is every one of his pieces and so many of them are there that he is one composer I could happily spend what remains of my life listening to without exception. I thought about choosing his wind quintet wonderfully titled Blow but finally as live music and concert attendance was clearly so important to and beloved by Giuseppe I have chosen a piece by Donatoni composed in the same year as Blow that brings back very fond memories of one of the most enjoyable concerts I ever attended.

5: Constança Capdeville (1937-1992):

Di lontan fa specchio il mare (1989)

Constança Capdeville

I finish today with another piece from that singular year of 1989 and another elegy. Portuguese composer Constança Capdeville wrote this haunting piece in memory of her great compatriot Joly Braga Santos who had passed away the year before. It tragically also serves as an elegy for Capdeville herself who left us only three years after this, long before her time was due.

Aside from being an elegy I have chosen this piece here for its title. Music is not the only art form that dabbles in sound, shape and structure, its sibling poetry is no stranger to these instruments and Italy is no stranger to some of the greatest poetry ever penned by humanity. The title of this piece is taken from the extraordinary poem La Ginestra by that word-wizard Giacomo Leopardi. Leopardi, Marchigiano, born in Recanati, not far from where many many years ago sitting with my back to the cathedral of San Ciriaco in Ancona and gazing upon the mirror of the Adriatic below and far out in front of me I had one of the greatest epiphanies - or something like that - of my life which always comes back to me when I see these words or hear this music. Such is music whether of sound or syllable, such is its power, its mystery, its sweetness. I think Giuseppe knew all this only too well.

Copyright © 16 April 2023

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain