- Turangalîla-Symphonie

- Senegal

- Ron Bierman

- Teatro Massimo

- Bob Auger

- Mark Stone

- Benedict Holland

- England

SPONSORED: Ensemble. A Great Start - Freddie Meyers' new opera A Sketch of Slow Time impresses Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. A Great Start - Freddie Meyers' new opera A Sketch of Slow Time impresses Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Last Gasp of Boyhood. Roderic Dunnett investigates Jubilee Opera's A Time There Was for the Benjamin Britten centenary.

SPONSORED: Ensemble. Last Gasp of Boyhood. Roderic Dunnett investigates Jubilee Opera's A Time There Was for the Benjamin Britten centenary.

All sponsored features >>

Fragments of Utopia

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at. - Oscar Wilde

I used to have a colleague who, when customers would make utterly insane demands or make known to us their ludicrous expectations, would calmly say 'the impossible we can do, but we draw the line at miracles'. Throughout Russian political and cultural history there seems to be an intoxicated love affair with the impossible, the otherworldly, the utopian. Maybe it has something to do with the inauspicious precedent of Tsar Peter I's building of paradise in a Baltic swamp where the immense loss of human life, which its realization necessitated, was a trivial inconvenience on the road to realizing a personal and imperial dream.

Peter the Great meditates on the idea of building St Petersburg next to the Baltic Sea - a 1916 painting by Russian artist Alexandre Benois (1870-1960)

Maybe in a world where catastrophe was common, unspeakable misery was on everyone's lips and where the ubiquitous presence of lamplit icons made the transcendent ever immanent, miracles had to be believed in because they just had to happen. Maybe it has something to do with the language. I have picked up a few languages through the years but sadly as yet Russian is not among them. Who could not yearn to learn a language in which as Vladimir Nabokov said:

Love rhymes with blood, nature with liberty, sadness with distance, human with everlasting, prince with mud, moon with many words but sun, and song and wind and life and death with none.

Maybe impossible translates into Russian as mildly inconvenient or irresistibly attractive. I do not know. Whichever, there is a history of seeing the utopian, the miraculous as desirable and eminently attainable.

But the heart wills and implores a miracle.

Oh miracle, let that happen which never happens.

The pale sky promise me miracles.

What I need is something not found on earth. - Zinaida Gippius

Before Stalin turned the Soviet Union into arguably the greatest false utopia of the twentieth century - there is strong competition for such a nefarious accolade - the energy unleashed by the Bolshevik Revolution coincided with (and in some part in however an intangible nebulous way was caused by) an already highly charged and wildly creative cultural period in imperial Russia fomented principally through Symbolism and exacerbated by the influence of various radical movements from western Europe in the first decades of the twentieth century: notably futurism and cubism. However, as has always been the case with Russia, whatever sparks made their way in from across Western Europe, they were kindled in that Slavic crucible into an utterly unique and inspired incandescence.

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)

Arguably the most apposite musical example of this phenomenon was that one-man whirlwind Alexander Scriabin. Scriabin started out naturally enough under the influence of Chopin but by the premature end of his life he had magnificently metamorphosised butterfly style by imbibing from a sacred chalice a heady concoction of Nietzsche, Blavatsky, decadence, symbolism and synesthesia to end up ever closer to the flame with his utterly utopian and uniquely megalomaniac vision as exemplified in his Mysterium:

There will not be a single spectator. All will be participants. The work requires special people, special artists and a completely new culture. The cast of performers includes an orchestra, a large mixed choir, an instrument with visual effects, dancers, a procession, incense, and rhythmic textural articulation. The cathedral in which it will take place will not be of one single type of stone but will continually change with the atmosphere and motion of the Mysterium. This will be done with the aid of mists and lights, which will modify the architectural contours.

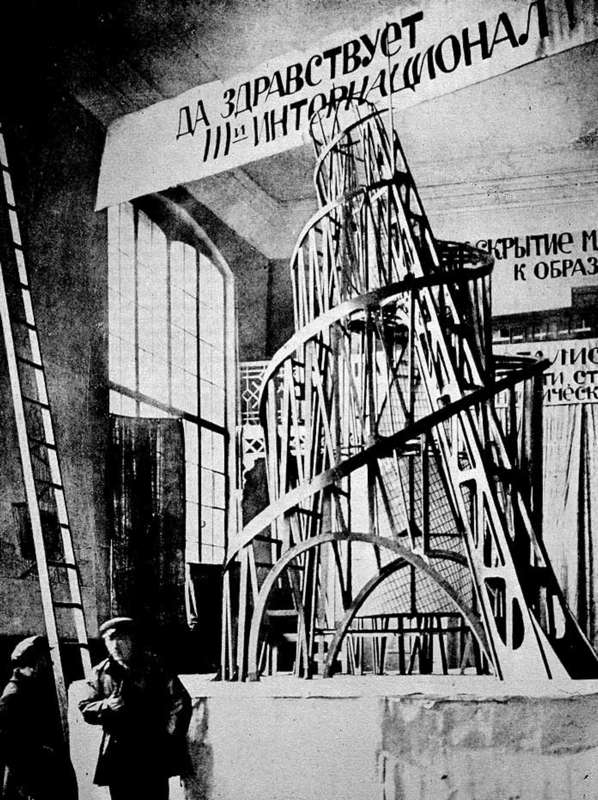

This prosaic description forgets to mention that the performance would take place in the Himalayas, that it would last for a week and finish with the end of the world no less and replace the human race with nobler beings (if only). Perhaps a forerunner of homo sovieticus. Not to forget my personal favourite; clouds hung with bells. Maybe Scriabin's Mysterium was the last dying flourish of Russia's Silver Age but like that similarly impossible symbol of the new Soviet Union: Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International, it remained unrealised by its creator. The fact that they were both unrealisable hardly seems relevant. Indeed when compared to the gloriously insane ambitiousness of these magical dreamers it seems churlish and pointless to point out the feasibility (or lack of) of such wondrous endeavours.

Vladimir Tatlin and an assistant in front of the model for the Third International

The extraordinary explosion of cultural zeal and vitality I mentioned above (whether evidenced in Tatlin's tower, Malevich's Suprematism, Lissitzky's Prouns, Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh's zaum, Mayakovsky's plays and posters, the poetry of Daniil Kharms or the unique collaborative experimental opera Victory over the Sun which united many of the talents above in a dizzyingly utopian tale of destroying reason, disposing of time and capturing the sun), also had many majestic musical manifestations. Since the fall of the Soviet Union thanks to the arduous work of many intrepid and dedicated musicologists and musicians more and more of these wonders are gradually seeing the light of day after decades of hibernation or sometimes of total oblivion and finally becoming better known to listeners outside of Russia and very probably inside Russia too.

El Lissitzky's poster for a post-revolutionary production of the collaborative opera 'Victory over the Sun'

From this purple period and for what remains of this article I want to focus on one of the lesser-known composers and on one of his works specifically. Just like Chaliapin, Elena Ivanovna Diakonova (better known to the world as Gala Dalí), Sofia Gubaidulina and the outstanding pianist and regular Classical Music Daily contributor Halida Dinova, Aleksey Zhivotov was born in Kazan in Tatarstan. I do not want any of these articles to be just biographical sketches of certain composers; sketches that can be found in many other sources but even if I wanted to give a basic outline of Zhivotov's life I would be very hard pressed to do so, as definite information about him and his life is almost non-existent. Indeed one article I have seen about him calls him 'a man who never existed'.

A pre-1918 postcard of Kazan

There are tantalising references to some of his pieces such as his oratorio Lenin from 1928, which included a speech choir whispering numbers accompanied by a piano that has all its keys depressed by a plank of wood. However the piece that is the reason for writing this article is his Fragments or Sketches for Nonet from 1929. Nine pieces for nine instrumentalists that typically do not last even nine minutes in total but once heard are never to be forgotten even if you are lucky enough to live nine lives. In its brief timespan the piece manages to crawl, grope, scrape, slide, hop, skip, saunter, dance and magic its way from the haunting to the humorous, from the daring to the dazzling from a hypnotic dream to a febrile frenzy.

I have never seen a score of this piece, which I would dearly love to, as I am still at a loss as to how exactly some of the sounds are actually produced. I am not completely sure which nine instruments are used. There must be some doubling on certain instruments otherwise there would be more than nine instrumentalists. I also do not know if some of the effects are called for in the score or just the result of decisions taken when recording. As in certain sections some of the instruments seem deliberately distanced which does add noticeably to the haunting atmosphere. Trying to give any definitive verbal description of this piece would be impossible. You may say that that would be completely in keeping with the tone and inspiration for this article and I would be inclined to agree, but with one very important caveat: I am not Russian, so I won't dare.

Listen — Aleksey Zhivotov: The Fragments for Nonet

(extract) Ensemble of the Soloists of Bolshoi Theatre / Alexander Lazarev :

There are sounds in here which would not be heard again for maybe half a century anywhere. This music is almost one hundred years old and yet it seems as if it still very much belongs to the future. Every time I listen in barely believable bewilderment, I am reminded of something Elliott Carter said in an off the cuff but very profound remark to Charles Rosen: The modern world is having a hard time being modern. Or maybe to paraphrase Hölderlin who, in one of his greatest and most lauded poems, said Aber Freund wir kommen zu spät, if we change that spät to früh this line could be applicable to that whole generation of extraordinary and extraordinarily creative and gifted Russian and Ukrainian firebirds. A glorious breed of dreamers which Stalin and his cultural henchmen utterly extinguished with the jackboot of socialist realism and the long icy shadow cast by the threat of the frozen Gulag. We are to be eternally grateful that since the Soviet Union melted into history, much of this magical music has risen phoenix-like from its dystopian oblivion.

Copyright © 4 October 2022

Robert McCarney,

León, Spain

TWENTIETH CENTURY CLASSICAL MUSIC

ECHOES OF OBLIVION - FURTHER INFORMATION