- John Reidy

- McDowall

- Parlophone Records Limited

- Vincent La Selva

- Anthony Poole

- Glamorgan

- Scottish Highlands

- Jerry Brubaker

VIDEO PODCAST: Come and meet Eric Fraad of Heresy Records, Kenneth Woods, musical director of Colorado MahlerFest and the English Symphony Orchestra and others.

VIDEO PODCAST: Come and meet Eric Fraad of Heresy Records, Kenneth Woods, musical director of Colorado MahlerFest and the English Symphony Orchestra and others.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

Opera is a Whole New World

As rehearsals begin for her new opera, Gabriela Lena Frank talks to RON BIERMAN

The opera El último sueño de Frida y Diego (The Last Dream of Frida and Diego) premieres in October 2022 at the San Diego Civic Center. I spoke with the work's composer Gabriela Lena Frank for more than an hour via Zoom while she was in Boonville, the rural area North of San Francisco where she lives. Although the opera is her first, her orchestral music has been performed by an impressive number of major orchestras including those of Cleveland, Philadelphia and Boston. And despite the challenge of a serious hearing deficiency from birth, she's produced music the New York Times described as 'brilliantly effective', while the Los Angeles Times chimed in with 'glorious'.

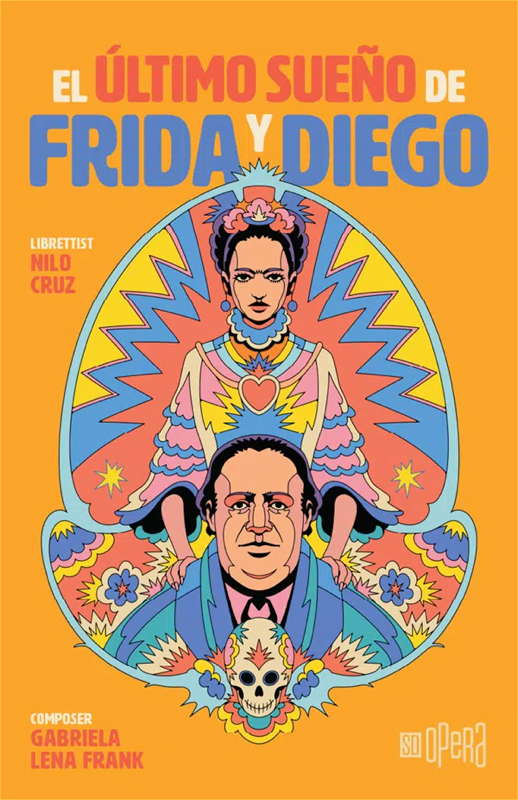

San Diego Opera's poster for El último sueño de Frida y Diego

Although Gabriela's hearing loss is substantial, it affects sound volume, but not frequency range, and she has perfect pitch. At five, the effect of hearing aids was startling. She's described it as the air suddenly coming alive - she heard her breath, a 3D piano sound, and birds singing for the first time.

Her experiences with sound have made her more introspective. 'Why is what I do important? How is my music going to change the world? I developed a high standard for what I thought could be done for people. And I think I became a different kind of artist because of that.'

Gabriela Lena Frank (born 1972). Photo © Mariah Tauger

Although Gabriela played her share of Bach and Clementi when very young, she never imagined a career in classical music. 'My older brother and I came of age in the 80s, a wonderful period of great pop music, and my parents played a lot of older rock and jazz.' Since her mother is Peruvian of Chinese descent, she also heard a lot of Peruvian folk-music.

The San Francisco Conservatory was a career-changing revelation. Before attending the summer before her senior year in high school she'd been thinking about political science and maybe law for college. But ...

'I'd been playing the piano in our living room in the evening with the lights off except for one on the piano. Just me in the darkness while I improvised. When I saw this school with a piano in every room, staff lines painted on the chalkboards, and music theory textbooks instead of horrible chemistry and algebra, I suddenly realized it was a world, a culture I could go into. My heart was booming that first day, and I thought, oh my god, oh my god, this is what I want to do!'

And she did. After high school, she entered Rice University music programs for bachelor's and master's degrees, then obtained a doctorate in composition at the University of Michigan.

Well-known composer William Bolcom was one of her most effective teachers and the first she mentioned. She admires his writing, but once an established pianist she recorded pieces by another of her Michigan professors, Leslie Basset, less well-known though a Pulitzer Prize winner.

'I felt keenly that he was on the verge of being forgotten. That was painful for me. The best way I could think of to thank him was to record his music. A phenomenal violinist and one of my best friends Wendolyn Olsen and I stayed with him at his house for a whole week. And every morning, he and his wife would feed us breakfast. Then Leslie, very frail at that time, would sit in the recording booth while we recorded. It was such a once-in-a-lifetime kind of experience.'

In a similar vein, she chooses to champion the works of modern composers she admires rather than the standard repertoire. 'You don't want to hear my Mozart. Haydn and Beethoven have enough champions.'

Gabriela's professional career as composer began with a piece for piano and violin commissioned for a small chamber music series in Durham, North Carolina. She and a fellow graduate were the first to perform it. She preferred chamber music at first.

'In part, I think, because I could relate to each one in the group. A symphony seemed a huge monolith, a mob. I couldn't get into it. But I did like concerts, so I started learning how to orchestrate. It's kind of ironic that my commissions are now mostly orchestral pieces, and I've fallen in love with the size and grandeur of a symphony orchestra.'

For a time after graduating from Michigan, Gabriela felt less than secure while freelancing as a composer, but gradually realized things were going well. I'll say!

She's currently composer-in-residence at the Philadelphia Orchestra and has held similar posts in Detroit and Houston. She's on the Washington Post's list of the thirty-five most significant women composers in history. She's won a Heinz Award in Arts and Humanity with a prize of US$250,000 for breaking gender, disability and cultural barriers in classical music composition. A partial list of commissions includes those from cellist Yo Yo Ma, soprano Dawn Upshaw, the King's Singers, major symphony orchestras and well-known conductors, and she has a Latin Grammy and nominations for Grammys as both composer and pianist.

But opera is a new challenge. 'Oh, my goodness yes, opera is a whole new world for me. It's a completely different animal, not just the art form itself, but the mechanics of performance.' Those mechanics include rehearsal times. While days or even hours are typical for orchestral rehearsals, opera's complex staging and singing demand weeks of rehearsals. The first of four performances is on 29 October 2022, and the composer will join the San Diego company almost three weeks before then.

El último sueño de Frida y Diego on the San Diego Opera website

It may be different, but she's well prepared for the challenge. Her Conquest Requiem is a previous large-scale choral/orchestral work, and a review of her catalog made me think an opera was inevitable. Most of Gabriela's compositions have evocative titles suggesting underlying stories and emotional reactions to inspirations such as ethnic history and traditions. Operas are just a more direct way to communicate.

'I think my desire to tell stories is my father's influence. He was a Mark Twain scholar at UC Berkeley for many decades and had my brother and I read literature with him and write short stories for him to critique. So it's something that comes naturally. I love it when I have the chance to write an essay, a short story or a song.'

She was tempted to write the libretto for her first opera, but her agent-publisher insisted on experience. The result was the start of a long friendship and working relationship with Pulitzer Prize winner Nilo Cruz.

'We're kindred spirits. He's one of our great writers, one of our most important. His writing is so lyrical, and beautiful, but also historically informed.'

While most operas projects begin with either words or music clearly in the lead, Cruz and Frank have more back-and-forth. It's a partnership she treasures. 'He gives me text he knows I may move around, and sometimes I show him musical ideas. I don't feel like I have to put forward perfect music. We can explore things together.'

Béla Bartók and Alberto Ginastera are the composers she mentions most frequently as influences, a bit of an odd couple at first glance. The common element is their extensive interest in ethnic music, Hungarian and Slavic for Bartók and Argentinian for Ginastera. Gabriela's heritage presents her with more ethnic choices than most. I count four continents in her recent family tree, North and South America, Asia and Europe. Her mother is Chinese/Peruvian and her father Lithuanian/Jewish.

Peru's influence was first to the fore. 'My mother has a Peruvian accent, fed us Peruvian fruit and meals, and played the country's music.' Gabriela began to combine elements of her European classical training with that of South American music. Her multi-ethnic, multi-cultural background became a huge influence on her work.

'At times, especially if there's text, there's a very strong narrative behind the music but I may not explain every detail. It's often more of a strategy to get my ideas going, just a feeling of cultural landscape. But my viola concerto, for example, is highly programmatic, a different spin on the classic Rusalka, a crying woman, a female spirit not at rest.'

The Picaflor (Hummingbird) is her latest inspiration. The Chronicles of the Picaflor is a forty-five-minute work commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra. 'It's on my table right now. I spent about four hours on it this morning. If I'm able to, I get started on a commission far ahead of time so I can explore different possibilities, try alternative endings.'

An excellent pianist, Gabriela, like many composers, sometimes uses the keyboard when developing a piece but has found it often inhibits her creativity. 'I generally don't write at the piano anymore. It's too real. If I can get away from it, I come up with things I otherwise wouldn't. So it's better for me to go into my fantasy music-land. The only thing I always do at the piano is music for piano. If I don't, I come up with things that are like, why did I think this was going to feel good? I can't even play it.'

That reminded me that I've often wondered how clearly composers can hear music in their minds while working on something new.

'Many of the composers I mentor can't do it, and then it gets better. But it can take decades of practice. I have to work at it if a score has a lot of experimental techniques and sound I've not worked with before. I'll have only some idea of what it sounds like just looking at the score, but the standard repertoire I hear as vibrant as can be. Of course, like tasty food, it's always better when you actually experience it live.'

Frank clearly enjoys mentoring composers as they develop. Five years ago, partly with personal funds, she and her husband Jeremy established the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy.

'Some time in the second year we started attracting a lot of attention and thankfully some funding support. We built an educational program about creativity at first.' Since it's a nonprofit on her own property, she has great flexibility as priorities change. 'We've had close to eighty composers come through our program now and gotten to know them really well. They text me all the time. I even get asked things like should I get a nasal septum piercing or not? So I'm something of a big sister mentor, and it has transformed me, made me a better composer and more aware of the industry through their eyes. I'm very hopeful when I see what these next generations are coming up with and how bold and unapologetically optimistic they are.'

A screenshot of the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music website

Gabriela is generally optimistic about the future of classical music and believes the key to expanding audiences is combining, as she has, its European tradition with invigorating new ideas from other cultures.

Civic outreach is another or her passions. 'We've been working hard with the local school district. We have a second home that graduating composers can live in for months, and in return they spend a certain number of hours of service working in the schools.'

Despite a busy professional schedule, Gabriela has a long history of civic outreach. Volunteering at a Michigan prison is probably the most unlikely example for a classical composer.

'I was a guest instructor at the Gus Harrison Correctional Facility when I was in grad school. (The facility is surrounded by double fences with razor-ribbon wire and two gun towers.) It was an exceptional experience as a grad student. I would take a music class in Schenker analysis, then go into this prison to talk to a group of people with a completely different set of values. It was a group for well-behaved Latino inmates from minor offenders to lifers. I spoke to them about Latin American composers and why they wrote the music they did.'

She listened to the inmates' stories and tried to make them feel there was value in those stories and that they could make something worthwhile of their lives.

'It was a very moving experience for me. It made me think about my own situation, to understand why I was doing music, and to wonder about some of the values I saw in my peers.'

Most unexpectedly, in addition to piano, Gabriela has studied Japanese taiko-drumming. Picture lithe but muscular men, bare arms stretched up to the limit and about to crash down violently on a huge drum.

'I learned taiko drumming as I was coming out of a long illness. During my last year at Michigan I started noticing I wasn't feeling well, and I was diagnosed with Graves disease which affects the autoimmune system.' She got through a first year but then, 'I got slammed even harder for the second phase which attacks your eyes, and as a hearing-impaired person, I really need my eyes. That lasted about seven years with multiple surgeries and radiation every day at a cancer center. I stopped playing piano because I couldn't see well and felt a terrific amount of pain.

'In the final phase, I needed something physical and something new to re-engage me and saw a demo at a street fair while we were living in the Bay Area. And they weren't super athletic. They looked like ordinary people with many body shapes, ages, sexes and races. So I signed up. and worked really, really hard at it for a couple of years.' Then the demand for her compositions took off and classes became less frequent and, perhaps, the need to take out her frustrations on a drum less necessary. 'I still have all my drumsticks and a taiko I bought from a local drum maker, and since we have a wonderful beautiful valley and neighbors are far away, I'll pull it out on the deck and have at it. Physically, it feels wonderful. I did aikido Japanese martial arts as a child in my youth, so I recognize a lot of the motions used.'

Add a concern for global warming to her incredibly busy life. 'My husband and I spend all our money on fire preparation. We're stewards of the land and that's very real to me. I teach classes on the climate crisis, and I think the industry must reexamine how much we fly around and other harmful practices. We have to figure out a new way of disseminating creativity and music, and as part of that I have a commitment to cut my travel dramatically. I've been taking trains. I have like hundreds of thousands of Amtrak points.'

Gabriela's family will be represented at her opera premiere in San Diego. 'Oh yes. They're coming. Are you kidding? My mother, my father. Absolutely. My husband.' Even more family members and friends will be at subsequent performances at the San Francisco Opera to see a story that has fascinated Gabriela for many years. Artist Frida Kahlo has been a hero since she came across her in one of her mother's art books. The handicapped mestiza's passionate love affair with fellow artist Diego Rivera seems an ideal subject for an opera and Gabriela Lena Frank an ideal composer to bring it to life.

Copyright © 26 September 2022

Ron Bierman,

San Diego, USA

FURTHER INTERVIEWS, PROFILES AND TRIBUTES