SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Well Realized - Varda Kotler and Israel Kastoriano - recommended by Geoff Pearce.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Well Realized - Varda Kotler and Israel Kastoriano - recommended by Geoff Pearce.

All sponsored features >>

- Kit Montgomery

- Silvius Weiss

- Lorraine Hunt Lieberson

- contemporary classical

- Hermann Mendel

- Éric Tappy

- Cecilia of Rome

- Melton Mowbray

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. A Fantastic Collection. Penelope Cave Panorama CD. Little-known harpsichord gems, strongly recommended by Alice McVeigh.

All sponsored features >>

A Rare and Novel Experience

Opera Warwick's production of Weber's 'The Marksman', heard by RODERIC DUNNETT

The inventive and imaginative Opera Warwick is now well into its second decade. Over the years I've reviewed half a dozen of its productions. Among the most memorable have been Cinderella (La Cenerentola: Rossini) and The Marriage of Poppea (L'Incoronazione di Poppea), as different as could be: the first of which positively exploded with zest, bubble and fun; whereas the latter shone with sensitivity, agony and pathos. Mozart (Figaro, The Magic Flute) has naturally featured; so has Smetana (The Bartered Bride) and Strauss (Die Fledermaus). Sets have usually been inventive, or better still. Productions involving, vital and perceptive. Singing of a quality to be admired and applauded.

Meticulously rehearsed, Opera Warwick (located in the UK outside Coventry) is a university ensemble, its achievement all the more impressive given that Warwick University has no music department. Compared with successful productions at the UK's full-time music colleges, in London, Birmingham or Manchester, I'd just as happily make my way to Warwick, on my doorstep, where talent shines, conducting can be masterly - witness Christian Blex, who has gone on to major positions in Scandinavia and Germany, winning the conducting scholarship of the Karajan-Academy of the Berlin Philharmonic from this September - and a wealth of vocal and instrumental intelligence is commonly on display.

If Poppea was a challenge, their latest undertaking, (Carl Maria von) Weber's most acclaimed opera, Der Freischütz (Berlin, 1821) was a big nut to crack. From the very opening, one of the most dramatic, indeed sensational overtures ever compiled, the tension rarely lifts. Spooky, sinister, desperate, diabolic, angelic, at its heart it exudes maliciousness, deception and corruption set against virginity and virtue. Only at the end does good win through, and even then only by a whisker. Little surprise, too, that Wagner and most since have seen it as the first truly German opera. Essentially correctly, though one or two other candidates pipped Freischütz to the post by just a year or two.

Flyer for Opera Warwick's 'The Marksman'

The Marksman is one of several titles used to render 'Der Freischütz' ('The Free Shot') into English. Controlling the awesome prelude, music director Farbod Salamat-Zadeh - a computer science postgraduate - immediately demonstrated an impressive, one might almost say masterly, control of pacing and command of the forces in front of him. Balance was a trickier matter, as, to be fair, the orchestra demonstrated slightly mixed abilities, with the initial (and some later) brass a little ropy, and the upper strings, with possibly a couple of absences, not always on the ball: tuning fine, but confidence not always on display. However there were compensations. (See below.)

Early on, the busy double bass (Maria Vasudevan) made several pleasing (and assured) contributions, and where the cello - Edward Neo or Duncan Webb - emerged, as it does for Agnes (Weber's Agathe), it shone, as it must, enchantingly. Highest marks perhaps to the entire woodwind department: two flutes (with piercing piccolos), paired clarinets, and Eleanor Brett's most touching oboe, all three hinted at in the overture. When the composer lets the bassoon(s) loose, the effect could be gripping, not least because Weber latches bassoons onto the brass quite often; and towards the end, heralding Max's entreaty to Prince(ss) Otokar, at key moments, one bassoon plays a significant, plangent role. Benjamin Winstanley's trumpet solo at roughly the same time made its mark - perhaps the most welcome solo offering from the brass. But the carousing horns boisterously had their moments. Elsewhere the brass was mostly massed, and a mighty noise they engendered.

Several, if not all, the solo roles bore white-chalk faces; possibly to stand out against a determinedly dark background (although Caspar's naturally suggested malevolence). And several were cross-cast, that is, girls played men in a nominally male-dominated text. The idea was fine: no real objection. Kilian, the Huntsman who has previously won the competition and who marshals the dance at the outset, was played with spirit by Isobel Cole. A fraction soft - was this down to the sound controllers? - but she nonetheless launched Act I with energy and verve, as it needs. The Head Huntsman, Cuno (German Kuno) was Matthew Calladine, whose bass timbres were gratifyingly firm, and whose expressive delivery of his major spoken passage - the story of his ancestor, of the same name, whose notable hunting exploit initiated the competition - was strong and sturdy, even if his attempt to try looking unsturdy lost something by his (seemingly undirected) inept lurching around with a walking stick. (Or was it, rather, a badge of office?)

One of the amusing features in this text is that presumably Cuno has told the assembled crowd the same story umpteen times before. But the Head Forester gave us a goodish start, and his interaction with the (here) six-woman chorus provided a chance to see how well moved and thoughtfully positioned even they were by director Thanos Adamidis, the palpable quality of whose well thought-through leadership could be seen in every section of the opera, and at every turn.

Opera Warwick's The Marksman: the loyal chorus members hope, despite all, for a happy outcome. Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

Well, like the rickety moving above, some other elements creaked. By now we meet the ultra-virtuous Max (Reuben Wilmshurst) and the wicked Caspar (Josh Taylor). They could not have been more differentiated, and this crucial fact benefited greatly from the supposed comrades - but in fact rivals' - acting. Wilmshurst's Max, with a highly impressive, all but beautiful and certainly commanding tenor voice which shone in his several big scenes and arias, was unremittingly stiff: hands invariably by his sides, dressed rather awkwardly - no fault of his - in an encompassing robe down to his feet was, let us say, not a top class actor. He badly needed taking in hand: and a few well-imagined ideas fed to him might have prevented him seeming so static. In a couple of places too, not necessarily from Max, a melisma – actually a signal feature with Weber - was omitted: Wagner would not have approved.

It is the daughter of head Forester Cuno (Matthew Calladine, centre) whom Max (Reuben Wilmshurst, left) hopes to marry. Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

But Max's first big aria – 'O! Diese Sonne' (anglicised, 'Ah, this sun') and his deeply yearning stanzaic rural ditty ('Durch die Wälder' – 'Through the woods/forest') were as perfect as one might hope. Maybe a hint (not too much) of vibrato might spare his impressive, consistently on the mark tenor from sounding a fraction pallid, like his moves and stance. And two lighting features that had a valuable, compelling impact were the follow-spot on Max, which followed him with remarkable accuracy and maybe underlined his virtue; and a yellowish green diagonal path (front left) which lent unexpected life to an otherwise darkened patch of the stage. Again, it seemed to be for Max: a path to purity and safety?

Max (Reuben Wilmshurst) clings to the green path of safety. Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

The very acceptable translation of The Marksman drew on that of Natalia Macfarren and Theodore Baker, from the mid nineteenth century, and served it well throughout. Nonetheless, one major warning. English is often the least easy language to enunciate lucidly - contrast, say, Italian. Hence the need even here for surtitles (which might be thought superfluous, but wrongly), is just as important as when an opera is sung in a foreign language. Let the words be seen as well as heard – even though the use of loudspeakers - design, manipulation and control by Jon Kowalski, Cat Heald and Vincci Chung - was all managed very acceptably. It's advice worth addressing.

So much for Wilmshurst's competently voiced tenor as Max. By contrast, Josh Taylor's Caspar (German Kaspar) was a revelation at every turn: endlessly frenetic, energised, zippy, restless, animated, boisterous, hyperactive to a degree I haven't seen before in many a Caspar elsewhere - London, Cardiff, and naturally in Germany. There's no doubting that Taylor, for all the high quality around him, was the star of the show. And that is how Caspar must be: fleeting and precipitate till the very moment of his death at the end (of which, more anon, for with that alone, he and Adamidis produced a visual masterpiece). This Caspar was a miracle, and was a perfect vehicle for, not least when inspiringly and tightly allied with, Salamat-Zadeh's conducting.

Alone in his tortuous world - the scheming ne'er-do-well Caspar (Josh Taylor). Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

What of the girls? The first of their two main scenes comes at the start of Act II. What is striking is the very large role, and arias/ariettas, allotted to the maid or confidante, Annie (Ännchen, Ingrid Berdall): 'A slender youth comes along', and later 'Once my dear cousin dreamed ...' were – allowing for a scintilla of flat intonation in launching the first: nothing that mattered - were charming, appetising, enticingly sung. Here was a rich, patently mature voice, which had the strength and firmness of what might verge on the professional. She encompasses fast runs with effortless élan. Any of the other voices (bar one, see the end), even Caspar, whose declamations benefited, however, from the upper speakers, albeit might gain from, indeed deserve, some additional guidance – they certainly receive some expert instruction - to firm them up, and to evolve the promising voices they already have into something fabulous.

Annie can be a pest as well as a friend, and tends quite often in stagings to be overacted. To one's relief, not so here; more stylish. Yet one of many nice touches was the way this production's Agnes (Agathe) dismissed her when she interrupted or intruded, a couple or times - especially the Agathe-Max exchanges. Annie goes off and vividly pouts. To be assertive where needed lent a little extra character to Israeli-born Noga Levy-Rapoport's Agnes. The maiden's two principal arias - the yellowish light which shines out above her could conceivably be intended as the sun, to which she refers as a symbol of her embracing of the good - are one of the joys of the opera. Gorgeously pure, innocent, angelic, god-fearing, presumably recognisably young and deeply in love, Levy-Rapoport sang with not a single flawed intonation, although perhaps a slightly harsh tinge to the voice for Agnes to be truly moving. She shone, charmingly, in duet with Annie, and equally in trio with Annie and Max, in which Annie virtually sustains the bottom line. At best Agnes' delivery was atmospheric, and her intensity apt. We cared about, and for, her.

The innocent, love-lorn heroine Agnes (Noga Levy-Rapoport) listens patiently to the vociferous Annie (Ingrid Berdall). Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

The highlight of the whole opera is the central casting by Caspar of the magic bullets. Here was one – in fact seven – moments which showed up Adamidis' nerve-racking direction (not to mention Weber's staggering orchestration) to such powerful effect. It's a scene that has to be got right, and never be limp or insufficiently mapped out. Josh Taylor's Caspar on his knees in the Wolf's Glen, shuffling around his seven tiny projectiles, was as sinister, eerie and poisonous as one could possibly imagine. Not just his actions, but his vocal delivery, were exceptionally fluent, fluid, fervid. The excitement intensifies when Max arrives, faltering and all but terrified; the whole atmosphere gets sharpened. Caspar has one aim: to trick his naïve fellow Huntsman into firing the crucial seventh bullet: one that he intends to ensure Max will kill his only beloved. At perhaps just one point, Max himself utters a prominent diminished fifth – the devil's interval; by then he is in deep danger.

The decisive moment approaches. Max (Reuben Wilmshurst, right) is tempted as the abhorrent Caspar (Josh Taylor, left) prepares to cast the terrifying seven bullets. Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

Manipulating this whole gory business is the heinous being, or non-being, or demon, Zamiel (Matthew Jenkins). The voice – his part is spoken – has to be ominous, menacing, grotesque. Clad here – an inspired touch – in bright scarlet, he is, you feel, omnipresent in almost every scene: indeed the threat he poses is sometimes more ominous still when he does not emerge, but addresses Caspar from offstage. In league, or in thrall, to Zamiel, Caspar will ultimately pay the price for dicing with extreme evil. We sense this might be so from Zamiel's ominous threat – 'him – or you'; ie 'One of you shall perish'. Zamiel's scarlet – a bit like a member of the Inquisition – is matched in several ways, but mainly twofold; by overhead scarlet lighting (occasionally tingeing, threateningly, the dominant eagle above, as if the hunting activity itself were deeply imperilled); albeit once, seemingly, misplaced, on Agnes' bed – or was that the exact intention?; - and a platform or dais or pallet (front stage right), sometimes spookily smoke-infused, which glares or glows, with an identical scarlet; there seems no getting away from this ghastly, non-human creature. To suggest the presence, seen or unseen, of maliciousness, all this set and lights detail works extraordinarily well. There's a lot of redness (some variety might be beneficial); and yet by its ample use the scarlet presence becomes all the more frightening. If Zamiel sang, it would be as vengeful and threatening as Mozart's Commendatore. Caspar is, in addition, an obvious forerunner of the villainous Lysiart in Weber's later major opera, Euryanthe.

The awesome Devil Zamiel (Matthew Jenkins) is summoned by the plotting Caspar (Josh Taylor). Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

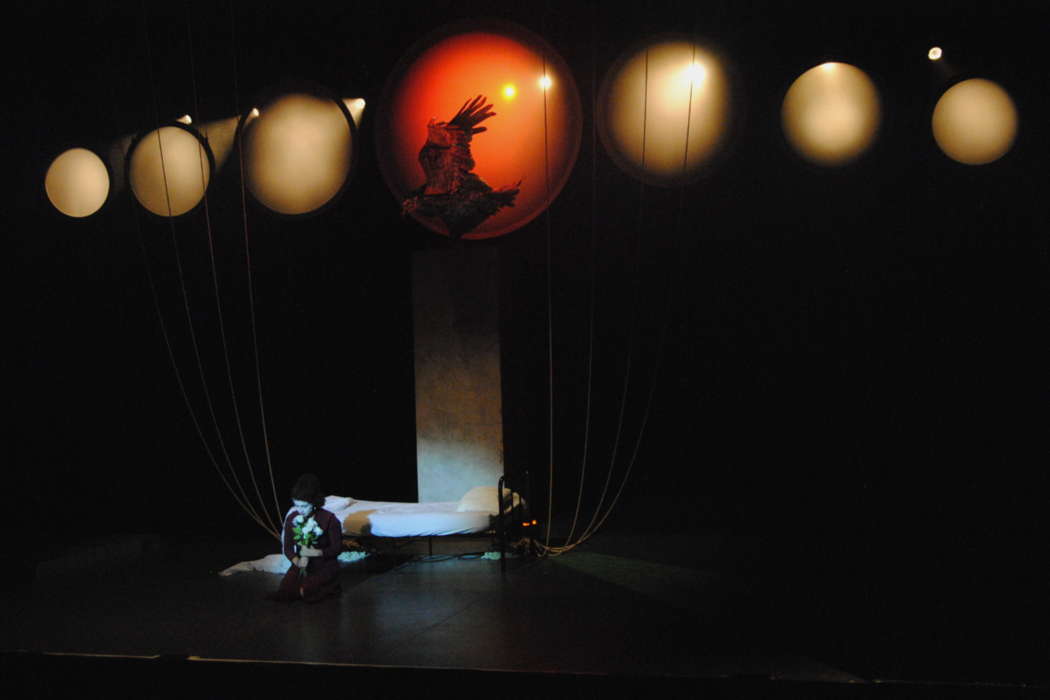

It's also in The Marksman's bullet-casting scene – and the orchestra here came right into its own, unerringly matched to the voice(s), especially given that it's immensely difficult to refine, given the ever-shifting orchestration – that yet another inspired piece of lighting came violently to life. Adamidis and his set designer, Casilda Serrano Villalobos (from Madrid), had designed a series of (let us say) saucers, discs or dishes high above the stage, all filled with a whiteish, or white-yellow light, which provided an intriguing but also worrying image from the onset, but which – one has already spotted there are seven discs – build up and flash one by one as the bullets are cast. For the last, number seven, the central circle bursts into light above the menacing silver eagle which equally presides over all the action: the creature Max originally shot even prior to the bullet casting scene, and which proves him the top-rate, but now haunted, Huntsman whom Cuno has so larded with praise.

The remarkable colour-changing set design (by Casilda Villalobos) for Opera Warwick's The Marksman, which hangs, doomlike, above the stage. Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

Weber's orchestration throughout the opera is, by general acclaim, some of the most imaginative found in any opera, not just of the period, but of any music of the nineteenth century. And the casting scene above all. Here, piccolos - Thomas Stanford and Bethan Davies-Asmar - scream. It really is hellish. But every inch of the orchestra is deployed, one way or another, to build up a horrific scenario. Here the orchestra (and conductor) emerged with superb flying colours. It's worth mentioning, too, that the two great full orchestra build-ups in the latter or final stages of this staggeringly inventive score were managed to perfection by this determined orchestral ensemble. They made it marvellously exciting. For these – both a masterpiece - there could be nothing but the highest praise.

Equally, every time one or both of the clarinets entered – and Weber, who composed two (or more) clarinet concertos, and several chamber works for clarinet, certainly knew how to use them to best effect – the sensation was mesmerising. Ruth Pugh and James Rawson gave us, together or individually, some of the most imposing moments, sometimes with flutes appended, as at the launch of Agnes' aria(s). Equally here one heard the oboe (Eleanor Bett) to splendid advantage. One does not often hear how significant a role Weber gives it (them).

As the end approaches, and the final grisly denouement, there comes another charming touch: the light-footed tripping of the children or maidens - here, three chorus members - who have come to offer a (presumably traditional, and elegant) bridal dance, to welcome and hearten the bride. Just as the full six-girl chorus were always well-directed and eloquent, so here the light-footed circling was particularly touching. The fact that it is interrupted or followed by the crisis over Annie having been supplied in error a black funeral wreath creates a very tidy if overawing contrast. And that Agnes bravely decides to make light of it only adds, advantageously, to Agnes' character. I thought I heard two or three solo viola passages around here. If so, not only Weber's originality, but the player's distinction, shone through.

Freischütz/The Marksman's famous Huntsmen's chorus, sung here by just a quintet, was astonishing. Microphones or not, the sound produced onstage by this well-tuned handful was sensational; just as an ensuing massed choir hit the right mark (as it were), evincing an astonishing echo of Sarastro's great masonic outpouring. What a rare and novel experience. The final scene it prefaces was mixed. Ottokar, a girl - 'Hence 'Princess'; Katie Gibson - had, to my mind, the most outstanding, professional voice, with a perfectly contrived, moderate, mild vibrato which in this role yielded wonder and delight. Clad in a marvellous regal emerald green, velvet robe, she had considerable presence, indeed exuded imperiousness.

The Princess Ottokar (Katie Gibson) takes her seat to judge the marksmen's competition. Photo © 2022 Tia Slavin

However the vital Hermit's appearance, bringing forgiveness and absolution, was supplied by another girl, Camille Metzger, a member of the chorus who here was still clad in a chorus brown robe - it could be argued any Franciscan would indeed wear brown. I'm afraid that aspect was a bit of a wet rag, and surely erroneous. Despite some nobility, the staging belied the huge importance of the opera's denouement.

But the finale was, despite this, pure magic. Max, static as ever, dutifully – and at huge risk – fires bullet number 7. Agnes falls on her face to be attended by a horrified Annie; but Caspar at the same moment falls on his back. To say that Josh Taylor's Caspar was mind-bogglingly, stupefyingly inventive would be a stultifying understatement. From first aria to his dying moments he was utterly believable; irresistibly cogent; endlessly creative. A human being par excellence, albeit one self-trapped on totally the wrong track. The range of jerks, twitches, spasms, convulsions and facial contortions, and most of all his last collapse, with the far knee bent and raised, as if beckoning or conceding to his fate, confirmed him as all but a National Theatre-worthy actor. Thus even at the close he managed an utterly remarkable range of talent. His singing voice - listed as bass but perhaps more a baritone - gained power when doomed, then faded tangibly towards his demise, even though further singing lessons could help his projection, and intensify even further his memorable delivery. Bizarrely, the final tremors and struggle with death were ravishing.

But what a performer, what a production, what standards, what a musical achievement by all, in an opera that is such a challenge to pull off. As always with Opera Warwick, I came away in awe of - and mystified by - its talent, bowled over, dazzled and enhanced.

Copyright © 30 June 2022

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK

FURTHER CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT THE UK