- Hollywood

- Michael Haydn

- Sir John Barbirolli

- Stephen Dodgson

- Konrad Boehmer

- Neuma Records

- Andrew Dawes

- Joseph Fort

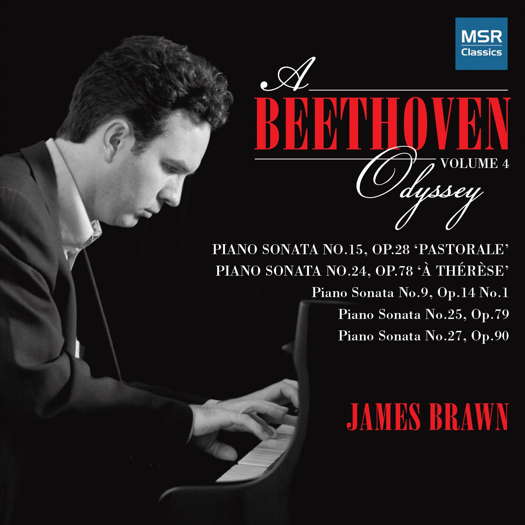

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Pure Magic - James Brawn's continued Beethoven Odyssey, awaited by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Pure Magic - James Brawn's continued Beethoven Odyssey, awaited by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Artificial Intelligence, including contributions from George Coulouris, Michael Stephen Brown, April Fredrick, Adrian Rumson and David Rain.

VIDEO PODCAST: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Classical Music and Artificial Intelligence, including contributions from George Coulouris, Michael Stephen Brown, April Fredrick, Adrian Rumson and David Rain.

Passionate Conducting

Daniel Harding concludes the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia's 2021-22 symphonic season in Rome, reviewed by GIUSEPPE PENNISI

Saturday 18 June 2022 was a hot day and many preferred to go to the beach. At the last concert of the 2021-22 symphonic season of the Santa Cecilia National Academy, there were several empty rows in an auditorium that holds three thousand spectators. Those who opted for the beach ought to know that they missed one of the best concerts of the season: Daniel Harding on the podium, Paul Lewis on piano and violin soloist Andrea Obiso. There were ten minutes of applause and ovation from an audience who knew the two pieces well, as they are performed very often in the Academy's symphonic concerts: Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A minor and the symphonic poem Ein Heldenleben (A hero's life) by Richard Strauss. The orchestra members have long applauded Harding by tapping their feet.

Daniel Harding and the Orchestra dell'Academia di Santa Cecilia. Photo © 2022 Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

I have known Harding since 1998, when, at only twenty-three years old, he alternated with Claudio Abbado on the podium of a memorable Don Giovanni with stage direction by Peter Brook at the Aix en Provence Festival. About twenty-five years have passed since then, and Harding has made an amazing (and deserved) career, but he always conducts with his arm wide and his back straight, carefully caring for the orchestra members who adore him. Passionate about football, a bit foul-mouthed towards certain stage directors (when you dine alone with him), he transmits to the interlocutors the passion he has when conducting.

Grieg's Piano Concerto is the Norwegian composer's best-known and most performed work. It is often compared to that by Robert Schumann: it is in the same key, the descending bloom at the opening is similar, and the overall style is considered to be closer to Schumann than to any other composer. Grieg had listened to the Schumann concerto played by Clara Schumann in Leipzig in 1858 and was greatly influenced by Schumann's style in general, having had as his piano teacher Ernst Ferdinand Wenzel, a friend of Schumann himself. In many recordings the two concertos are often paired.

The work also reveals Grieg's interest in Norwegian folk music: the initial flowering is on a motif typical of popular music. Grieg was an excellent pianist, but at the concerto's debut on 3 April 1869 in Copenhagen, Grieg was not present, having engagements with an orchestra in Christiania (now Oslo).

An attentive and scrupulous connoisseur of European Romantic literature and a scholar of the instrumental refinements by Wagner and Liszt, Grieg could not classify himself as an imitator of other people's styles or a follower of fashions alien to the spirit of Norwegian folklore. The hugely popular Piano Concerto was composed in 1868, during a holiday in the Danish village of Sölleröd, north of Copenhagen.

Harding (and Paul Lewis in his dialogue with the orchestra) highlighted the freshness of the musical ideas and the elegance of the orchestration, articulated according to Grieg's very personal style.

Paul Lewis, Daniel Harding and the Orchestra dell'Academia di Santa Cecilia performing Grieg's Piano Concerto. Photo © 2022 Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

A sweet melodic serenity characterizes the first movement, but it is above all the theme of the Adagio, entrusted to the orchestra and taken up by the piano with dreamy Chopin delicacy, which involves the listener emotionally with tenderness typical of Nordic lyricism. The third movement has a particularly varied dynamic with easy sonic brilliance and on Norwegian dance rhythms. Harding (and Lewis) emphasized the fiery moments and the more purely lyrical ones.

Paul Lewis, Daniel Harding and the Orchestra dell'Academia di Santa Cecilia performing Grieg's Piano Concerto. Photo © 2022 Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Ein Heldenleben was composed in 1838 and conducted by Richard Strauss on 3 March 1899 in Frankfurt. Strauss conducted the work twice, in 1909 and 1913, with the Cecilian ensembles in Rome at the Augusteo concert hall. With this work, Strauss consciously concludes his cycle of symphonic poems, and the literary theme is now openly autobiographical. The hero is undoubtedly the composer himself; he reconsiders his entire human and artistic existence to clarify to himself and to others the meaning of his work and the experience gained so far, as well as (in the solo violin part) the complex relationships with Pauline, who was his wife for over fifty years. It is not for nothing that the score includes a large number of self-quotations, especially from his previous symphonic poems.

The program is carried out in six distinct but seamless sections:

- The hero: a decisive musical gesture full of strong-willed energy announces the symphonic poem's protagonist; three other themes depict his power of imagination, the depth of his feeling and his vitality.

- Opponents: The hero's enemies are naturally petty and petulant; the play of themes and stamps clearly draws the contrast between these grotesque presences and that of the hero.

- The companion: the expansions of the solo violin are entrusted with the characterization of the hero's companion and, through her, of the eternal feminine; the representation of the different moods of his relationship with her. The tender conversation of the two themed-character is followed by an appeal of the trumpets.

- The battlefield: the themes of the hero and his enemies return in a depiction animated by the generous use of brass and percussion; the inevitable victory is greeted by a triumphal song in which the hero's companion participates: but the deafening blows to the eardrum insinuate a dark and distant threat.

- The works of peace: the most private sense of the poem is clarified in the parade of quotations from Strauss' works: Don Juan, Zarathustra, Death and Transfiguration, Don Quixote, Till, Guntram, Macbeth, the Lied Dream in the Twilight; in this very skillful mosaic, the theme of the opponents breaks once again, but briefly.

- Withdrawal from the world and the end of the hero: an almost pastoral episode symbolizes the inner stillness finally reached after so many adventures; a last moment of contrast is overcome by the transfiguration brought by the theme of the companion.

Ein Heldenleben: Daniel Harding and the Orchestra dell'Academia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. Photo © 2022 Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

In one of his most complex and finely elaborated works, the thirty-four-year-old Strauss takes leave of a chapter of his artistic history and a whole century: his twentieth century will be above all opera and theatre in music.

Andrea Obiso performing one of the violin solos in Richard Strauss' Ein Heldenleben. Photo © 2022 Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Harding, the orchestra and Obiso, in his small but important part, offered a performance full of passion with which Strauss marks the end of one phase and the beginning of another, transmitting this to an enthusiastic audience.

Copyright © 21 June 2022

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy

ARTICLES ABOUT THE ACCADEMIA NAZIONALE DI SANTA CECILIA