ARTICLES BEING VIEWED NOW:

- Régine Crespin

- Hector Berlioz

- Ruth Railton

- Marián Varga

- Profile. A Very Positive Conductor - Paul Bodine talks to Los Angeles Opera's Music Director Designate, Domingo Hindoyan

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

- in depth

- Bob Chilcott

- Toshio Hosokawa

- Moldova

- Elinor Remick Warren

- Justin Connolly: Ceilidh

- Nicholas McGegan

- Leroy Anderson: Sleigh Ride

A Dramatic Entrance

MATT SPANGLER and LUCY MAURO shine a light on an American classical pioneer

The high society women and men, in their tailor-mades, nipped shirtwaists, tailcoats and bowlers, paid scant attention to the slender and petite young woman, her hair tied back in a chignon, as she made her way nervously down the gaslit corridors of the Boston Music Hall to her balcony seat. Little did the patrons know that the woman who slunk low in her blue and white moreen chair, her head swimming with thoughts of the million little things that could go wrong with the evening's performance, was about to make music history.

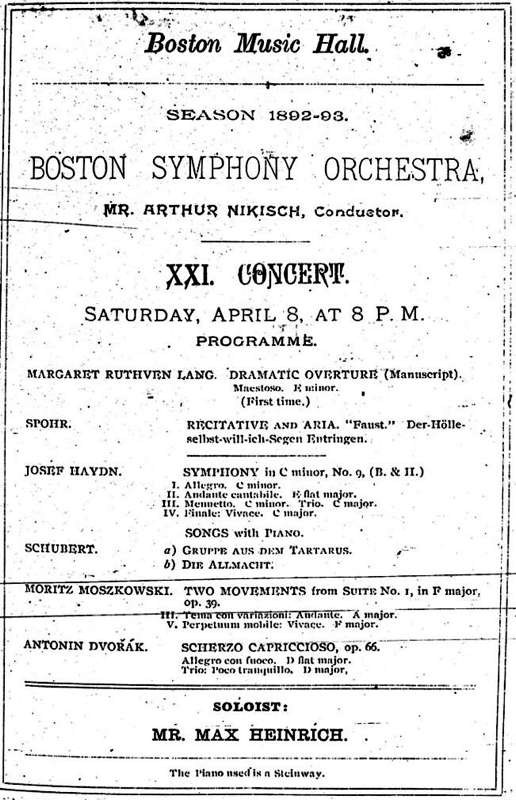

The young woman was Margaret Ruthven Lang, and it was the evening of 8 April 1893. Under the baton of Arthur Nikisch, her Dramatic Overture became the first piece composed by a woman performed by a major American symphony orchestra. The score does not survive - likely tossed onto the hearth during one of Lang's periodic purges of her work - but the program, which has been preserved, frames the piece in terms of influences by the great male composers of the time.

Margaret Lang (1867-1972) in circa 1900

'The dramatic overture,' the program note begins, 'shows the same general tendency to adhere to the spirit of the sonata form, with a very free interpretation of the letter of the law, that we find in many of Schumann's symphonic movements.' The note goes on to say the 'overture is scored for the classical "grand orchestra", with trombones, big drum, and cymbals, but without bass-tuba, bass-clarinet, English horn, or any of the unusual instruments that go to make up the modern "Wagnerian" orchestra. It is especially noticeable, too, that the stronger brass instruments - trumpets and trombones - have been reserved for special effects, and often do not figure at all in fortissimo passages. In this the composer has followed both Beethoven and Wagner in one of their most characteristic veins in instrumentation.'

Concert poster for the Boston Symphony Orchestra's 8 April 1893 concert

The performance was met with great enthusiasm from the crowd, who, before the players could resume with the Spohr, Haydn, Schubert, Moszkowski and Dvořák works that filled out the rest of the bill, called back Nikisch three times. It would be another three years, however, before the Boston Symphony's celebrated programming of Amy Beach's Gaelic Symphony (Symphony in E minor, Op 32).

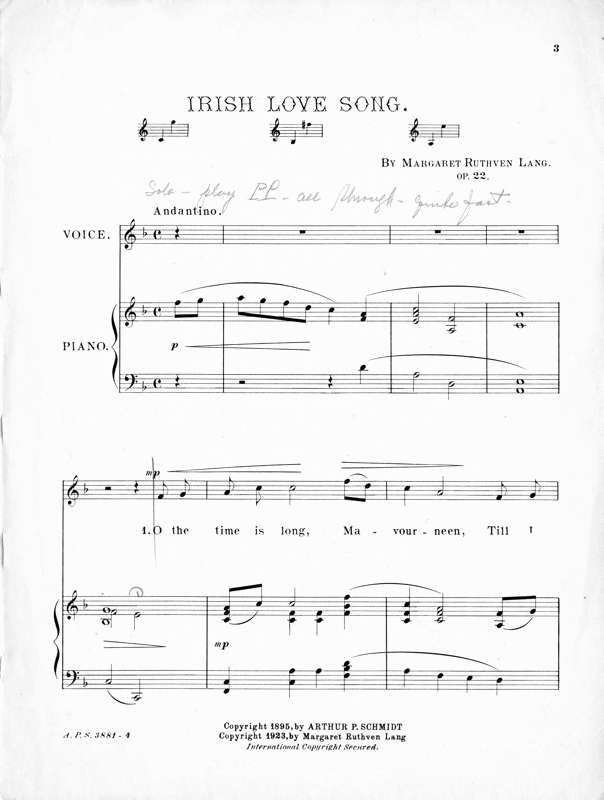

Like Beach, her Second New England School friend and colleague, Lang's star gradually rose over the American Romantic era. Fueled by her connections to Wagner and Liszt (Lang's father was renowned Boston conductor B J Lang), and private instruction from George Chadwick (later named director of the New England Conservatory), Lang published approximately 150 orchestral and chamber music works, piano solos, arias, and songs between 1887 and 1917 (and is believed to have written some thirty other works that, like the Dramatic Overture, were destroyed). Her compositions were performed on both sides of the Atlantic, including the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, which featured several of her songs; the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, which featured the Witichis Overture; and an 1896 performance of the Armida aria for soprano by the Boston Symphony. She sold nearly 121,000 copies of the sheet music for Irish Love Song, penned in 1895, and by 1897, according to one account, she had 'attained a position which puts her among the four leading women composers of the time', the others being Beach, Cécile Chaminade and Augusta Holmès.

The opening page of Margaret Lang's 'Irish Love Song' from the Historic Sheet Music Collection of Connecticut College

Lang abruptly quit composing in 1917, at the age of fifty, stating modestly she 'had nothing to say' at that point. An Episcopalian, she devoted much of her remaining fifty-five years writing religious pamphlets she called 'Messages from God', which she distributed around the world using royalties from her music sales. Four years before her retirement, Stravinsky ignited a seismic change in music in Paris, and the work of Romantics like Lang quickly fell out of fashion and faded into obscurity.

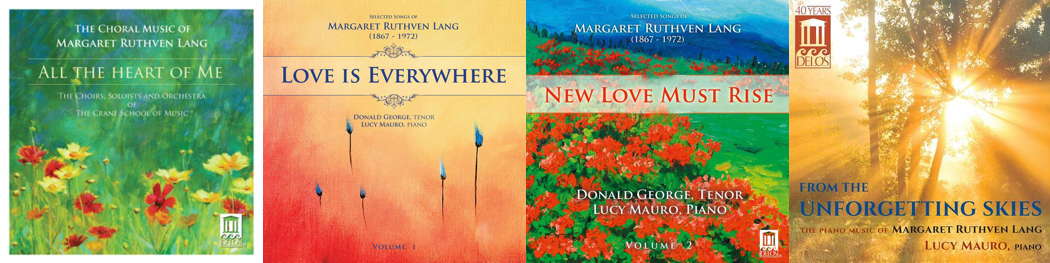

Delos Productions' Margaret Lang CDs. From left to right: All the Heart of Me: The Choral Music of Margaret Ruthven Lang (DE3426, 2014), Love is Everywhere - Songs of Margaret Ruthven Lang, Vol 1 (DE3407, 2011), New Love Must Rise: Selected Songs of Margaret Ruthven Lang, Vol II (DE3410, 2012) and From the Unforgetting Skies: The Piano Music of Margaret Ruthven Lang (DE3433, 2013). CD cover images © 2011-14 Delos Productions Inc

Lang's extant compositions can be heard on Delos' All the Heart of Me: The Choral Music of Margaret Ruthven Lang; Love is Everywhere - Songs of Margaret Ruthven Lang, Vol 1; New Love Must Rise: Selected Songs of Margaret Ruthven Lang, Vol II; and From the Unforgetting Skies: The Piano Music of Margaret Ruthven Lang.

Copyright © 11 May 2022

Matt Spangler and Lucy Mauro,

USA

ARTICLES ABOUT THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

FURTHER INTERVIEWS, PROFILES AND TRIBUTES