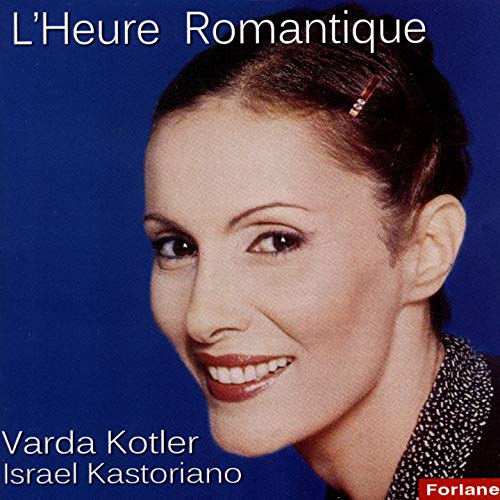

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Well Realized - Varda Kotler and Israel Kastoriano - recommended by Geoff Pearce.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Well Realized - Varda Kotler and Israel Kastoriano - recommended by Geoff Pearce.

All sponsored features >>

- William Alwyn

- Chamber Orchestra of Europe

- Joan Sutherland

- Scandinavian

- Woltera de Marez Oyens

- Giacomo Meyerbeer

- Francesco Gasparini

- Percy Whitlock

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

An Interesting Contamination of Genres

GIUSEPPE PENNISI reports from the first Italian performance of 'The Passion according to St Mark' by contemporary Polish composer Paweł Mykietyn

On 9 April 2022, I attended a grandiose concert with a very large number of performers, unlike those usually heard at the Istituzione Universitaria dei Concerti (IUC) which, for its space and audience, prefers chamber music. It is the result of collaboration between Italian institutions (the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, the Ready Made Ensemble choir) and Polish institutions (the AUKSO Chamber Orchestra of the City of Tychy) as well as collaboration with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Polish Institute of Rome and with the support of the PWM Edition and co-financed by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Poland. On the program, an event, the first Italian performance of The Passion according to St Mark (Pasja wg św Marka, 2008), a large-scale work by Paweł Mykietyn (born 1971), one of the most interesting composers of the new Polish school.

Online publicity for Paweł Mykietyn's Passione secondo San Marco

Poland has an important tradition of 'music of the spirit' (religious music), which has largely accompanied the efforts of Solidarność, the free trade union that was formed in 1980, following the workers' strikes at the Gdansk shipyards and which led to the end of the communist regime. Suffice it to recall the Passion of Krzysztof Penderecki (1966), performed all over the world and brought in 1983 to Rome too. (I had the opportunity to listen to it in Washington, where I then resided, in the mid-seventies.)

The Passion according to St Mark by Paweł Mykietyn, presented in world premiere at the Wratislavia Cantas Festival in September 2008 (and now in Italian premiere at the IUC), distances itself from that of Penderecki who knew how to combine tradition and modernity, along a cutting-edge road. In 2008, a heated debate developed. The specialized press, not only Polish, spoke of 'an hour and a half of uncomfortable but necessary music', of the 'microtones of death' and of 'a collage of individual sentences, from which emerges the story of the pain, fear and suffering of the citizen Christ'. For everyone it was clear that this was music which deeply touches the listener of today. Mykietyn replied: 'I wanted on the one hand to be witnesses, observers of those events, on the other hand that all this was happening today, now.'

Today, fourteen years after the world debut, this new Passion of the third millennium expresses the world and the man of our times: we live, in Lent 2022, marked by the tragic war in Ukraine. Mykietyn's music speaks to us even louder than suffering, pain and death.

Paweł Mykietyn's The Passion according to St Mark at the Aula Magna della Sapienza in Rome. Photo © 2022 Andrea Caramelli and Federico Priori

In the first place, the libretto, written by the composer, does not follow St Mark's Gospel but is made up of the passages of the four Evangelists and the prophet Isaiah and treats the story backwards: it begins with a brief episode on the death of Christ on the Cross to go back to the garden of Gethsemane. The text is in Hebrew, except for the one entrusted to the reciting voice - Luca Di Prospero, who impersonates Pontius Pilate - and which uses the language of the place where the Passion is performed. Jesus is the mezzo-soprano Urszula Kryger. The others, a natural voice (Kasia Moś, a pop and jazz singer), the choirs (from which the basses have short solo parts) represent the crowds and the other dramatis personae of the Passion.

From left to right: Kasia Moś, Luca Di Prospero and Urszula Kryger performing Mykietyn's The Passion according to St Mark in Rome. Photo © 2022 Andrea Caramelli and Federico Priori

On a minimalist musical carpet (especially at the beginning), such as to remember Philip Glass and also Arvo Párt, microtonalities, grafts from jazz, great choral interventions, daring use of amplifiers (for crowds) and music recorded on tape are inserted. There is a rock band with electric guitars next to the string instruments tuned in microtones, a tuba next to the saxophones, a percussion set, a classical mezzo-soprano, a boys' choir and a rock singer, a reciting voice; the interludes between the parts are the 'song of the cicadas', reproduced by the tape. We are constantly surprised by the changes in musical poetics, shreds of events, contexts, mixtures of tempos. It is not avant-garde in the strict sense, but an interesting contamination of genres, which expresses the sense of contemporaneity of a work of great emotional impact that enchants, moves and at the same time surprises the listener with unexpected inventions. Above all, there is nothing obvious: timing, musical aesthetics, words, types of narration - everything mixes. The essence of the Passion (understood as suffering and also as pesach – passage) keeps us in suspense, in tension, in amazement, in waiting. Even the Hebrew text, rarely interrupted with recitations in the local language, is incomprehensible, alien to the biblical tradition of Christians in Europe.

Conductor Marek Moś performed very well with the various ensembles on stage, which is not an easy task. The IUC audience is accustomed to contemporary music. They followed the performance with great interest and, at the end, exploded in about eight minutes of applause.

Copyright © 13 April 2022

Giuseppe Pennisi,

Rome, Italy