- Evgeny Kissin

- sixth century

- lute music

- EUCO

- Jennifer I Paull

- light music

- Wei Wang

- Reverence for Life

Changing Moods

MIKE WHEELER listens to a talk about, then a performance of, Elgar's Symphony No 1

If anyone was going to write the first great English symphony, Elgar would be the one to do it. That was broadcaster and writer Stephen Johnson's opening gambit in his latest Discovering Music event, on Elgar's Symphony No 1 – Royal Concert Hall, Nottingham, UK, 22 February 2022. It followed the familiar pattern: he talked us through the work, with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted on this occasion by Mark Wigglesworth, on hand to provide live illustrations, followed after the interval by a complete performance.

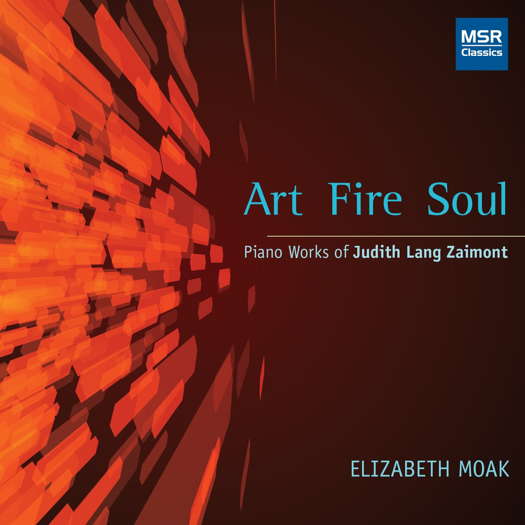

BBC online publicity for the 22 February 2022 event with, inset, a photo of Mark Wigglesworth conducting

Johnson's take on the symphony was to view it from the standpoint of Elgar's complex personality, prone as he was to 'alarming mood swings'. He directed our attention to the link from the opening – in serene, confident A flat major – into turbulent D minor; 'all is flux now', he commented. He gave us three examples of Elgar's command of orchestration. In one fully-scored passage the cellos are placed particularly high in their range, giving it a sense of strain. Johnson suggested that Elgar's 'dazzling' brass writing would have astonished the work's first hearers. Among a number of points at which the opening motto theme reappears, one in particular, played from the back of the orchestra, gave the effect of physical, as well as emotional, distance, while a later reappearance gave us 'at last a real memory of something solid'.

The second movement begins with, in Johnson's words, a 'dark-toned, nervous, edgy' march. It is followed by a gentle, more limpid episode, which Elgar once told an orchestra to play 'like something you hear down by the river'. Johnson suggested the spot Elgar may well have had in mind – where the River Lugg joins the River Wye, near Hereford, an area he knows well.

The point at which the River Lugg (bottom right) flows into the River Wye, as the Wye turns a corner, near Mordiford in Herefordshire, UK. Photo © 2022 Keith Bramich

The process of gradually slowing the opening string phrases down to form the main theme of the third movement was, said Johnson, 'as though the river itself is slowing down steadily'. When we enter the third movement, 'the transformation is absolutely majestic'. Johnson also drew our attention to a subtle thematic connection with the motto idea.

He characterised the dark, uncertain introduction to the finale with a quotation from Macbeth: 'something wicked this way comes'. He reminded us of the tonal distance between A flat and D, with an illustration from the principal harpist. And so he took us back to Elgar's mood-swings, via a quotation from WB Yeats: 'The intellect of man is forced to choose Perfection of the life, or of the work' and Michael Tippett's 'I would know my shadow and my light'. But the motto theme finally emerges complete and triumphant at the end, Johnson producing the engagingly apt image of a galleon 'crashing through the waves, sending spray in all directions'.

The complete performance began with a broad, confident take on the motto theme. The restless D minor section included some positively volcanic outbursts, following which a passage for solo violin sounded plaintive, almost a quiet protest. Amid moments of limpid tranquillity, shadowy recollections of the motto theme sounded almost defiant. Conductor and orchestra were particularly successful in projecting a sense of breath-taking quietness in the final pages.

It's a pity the opportunity wasn't taken to seat the first and second violins left and right on the platform, given the number of passages in which material flies backwards and forwards between the two. This is particularly true of the second movement. Wigglesworth and the BBCPO launched it in white-hot fury, in contrast to which the 'river' music was clear and fresh. After the slowing-down process, the third movement began with a magical sense of a corner having been turned, though also tinged with sadness. The movement's final pages is one of the greatest passages in all Elgar. The gently radiant tranquillity, the intense hush – here they were simply riveting.

The finale followed without a break, and with the changing moods deftly navigated. The clipped march figure, speeded up from the introduction, verged on the brutal, so its eventual flowering into broad, lyrical serenity was all the more moving. As the performance continued there was a suggestion that the eventual outcome might even be in doubt but, after the motto's final appearance, orchestra and conductor really went for the race to the finish; the ending was as big an orchestral whoop of joy as you could imagine.

Copyright © 3 March 2022

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK