- Pierre Hasquenoph

- Vox Classics

- Sarasate

- Matthias Goerne

- Dora Pejačević

- Liapunov

- Alban Berg

- Jeanne Shapiro

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

DISCUSSION: Composers Daniel Schorno and John Dante Prevedini discuss creativity, innovation and re-invention with Maria Nockin, Mary Mogil, Giuseppe Pennisi and Roderic Dunnett.

DISCUSSION: Composers Daniel Schorno and John Dante Prevedini discuss creativity, innovation and re-invention with Maria Nockin, Mary Mogil, Giuseppe Pennisi and Roderic Dunnett.

Excitement at Coventry Cathedral

RODERIC DUNNETT experiences Nitin Sawhney's new work 'Ghosts in the Ruins'

There was a great deal of excitement recently at Coventry Cathedral. The versatile composer and polymath Nitin Sawhney had accepted a fascinating commission, jointly initiated by the cathedral and Coventry City of Culture 2021, to compose a major work to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of the consecration of the splendid new Coventry Cathedral.

This amazingly modernist, original and visually powerful building took almost a decade to plan and construct during the 1950s, following the destruction of its predecessor, the Gothic St Michael's, by Luftwaffe bombers in November 1940.

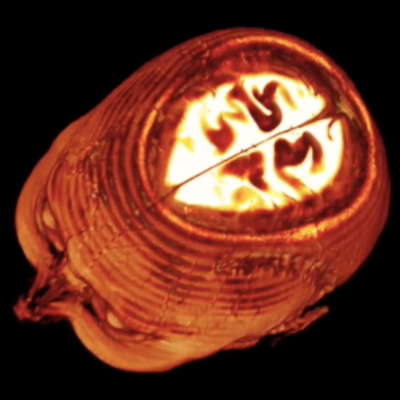

Coventry Cathedral bomb damage in 1940

Nitin Sawhney was raised in Kent by British Indian parents. His achievement and reputation are utterly remarkable. He has been viewed, since roughly 1993, as a world-class producer, as well as songwriter, and amongst many other excellences as an orchestral composer who ranks as an incredibly pioneering, multi-cultural initiator and expert, who deftly merges Asian and also African influences with a wealth of further worldwide influences. His masterly pioneering work with young ensembles is one of his most significant undertakings.

A notable recipient of the Ivor Novello Lifetime Achievement award in 2017, and a host of distinguished other awards, Sawhney is now Chair of Trustees for the PRS (Performing Right Society), the crucial body which looks after the entitlements and needs of UK composers, and serves as patron of a host of film, music and educational bodies. He also acts as a very active chairman of the film body BAFTA, and recently worthily received a CBE.

Nitin's wide experience in music, film - some fifty scores, an outstanding and extensive output: including in 2018 the whole score for the acclaimed movie Mowgli, Legend of the Jungle plus Midnight's Children after Salman Rushdie, and (for TV History Channel) The Real Nelson Mandela - plus dance, theatre - Simon McBurney's superb theatre company Théatre de Complicité, numerous other stage works for other spheres, and his bold, unceasing curiosity in exploring a wide range of music earned Sawhney the reputation of 'a formidable polymath'.

Nitin Sawhney in Brixton, London. Photo © 2017 Suki Dhanda

Ten years ago a modest celebration of Coventry Cathedral's fiftieth anniversary paid tribute to the grim destruction of the previous building. But it is greatly to the present cathedral's credit that in conjunction with the last stages of the city's somewhat curtailed (because of COVID) year as UK City of Culture, it has reached out and brought to radiant life a truly original, aptly entitled musical work, Ghosts in the Ruins, which has received its dramatic premiere, and which aspires to evoke not just that appalling experience of destruction but - surely more significantly - the richly positive, fresh, original and arguably unique spirit of the shared ministry of both new and old combined.

This wondrous occasion was truly atmospheric - in fact there have probably been few such overwhelming and visually evocative adventures in the present cathedral's life. First, because the occasion embraced both locations, opening up (with numerous superbly displayed black and white wartime photos) the new; and then transferring - the entire fascinated audience - to the roofless remains of the old to evoke a vision of a shared future.

A scene from Nitin Sawhney's Ghosts in the Ruins at Coventry Cathedral

Secondly, because of the huge number of active performers, the best of the singing felt quite mesmerising: the Cathedral choir was directed by the splendidly gifted Director of Music, Rachel Mahon, but the work also featured entrancing community groups, including some supportive instrumental playing which added a special vividness to several sections.

The declared introduction indicated clearly the worthy aspirations: 'Created with Coventry's professional musicians, poets and communities, Ghosts in the Ruins will explore contemporary ideas of peace and reconciliation' and reflect Coventry as 'a city of sanctuary, with a strong history of helping refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants', and - thanks especially to the initiative of its pioneering Deans (Provosts) Richard Howard, and then the immensely active Harold (Bill) Williams - worldwide associations.

'The aim of music and text', declared the introduction, 'will explore themes of acceptance, healing, transcendence, hope, resilience, regeneration and reconciliation in relation to contemporary conflicts, an acknowledgement of the destruction of the past as well as hope for the future of the world.' These, the spreading of such aspirations, are the aspiration of the new cathedral to societies around the world, not last to America, have been, since its foundation, the passion and determination of Provost Williams especially; and the goal and ambition. And the dream of a worldwide spread has proved, one might assert, a triumph.

A scene from Nitin Sawhney's Ghosts in the Ruins at Coventry Cathedral

The dazzling impact of the occasion - shifting colours played onto the projecting edges of the old building, a constant feeling of change and perhaps new life - was undoubted. The questing new music commissioned from Sawhney was even designed to pay some level of tribute - most appropriately - to Benjamin Britten's War Requiem, the major, exotic work designed for the new cathedral's opening festival in 1962. Sawney himself read most movingly at the outset from one of those focal, evocative, culminating passages of Wilfred Owen originally set by Britten.

It would be nice to say that a measure of parallelling was achieved here in the music; but perhaps this was not the actual purpose. Sawhney has gifts of varying his movements - vivid scherzo, achingly beautiful, passages, especially enchanting chorale-like, soothing sequences, a distinguished nobility, and an especially fresh, original use of gaps or pauses, each one captivating; and an almost miraculous, quite frequent an evocative use of a solo violin. But - unless some detail was furnished with the printed words (of limited use in the darkness), the musical and textual aspect - that healing and transcendence and regeneration - seemed well nigh, or almost, lost.

But the resilience and regeneration we did feel, wonderfully strongly. This was a major strength. So - a large scale event, vivid, exciting, awe-inspiring, visually inspiring, we were treated to. The very full audience will have felt that strongly. And how thrilling that was at its best.

Copyright © 9 February 2022

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK

FURTHER CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT THE UK