- Grand Piano Records

- string quartets

- folksongs

- Galina Ustvolskaya

- Mirella Freni

- Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli

- Langgaard: The Music of the Spheres

- Tomáš Brauner

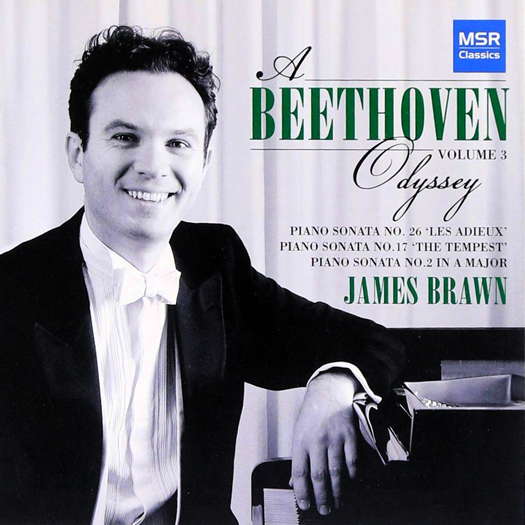

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

SPONSORED: CD Spotlight. Masterful Handling - Volume 3 of James Brawn's Beethoven, praised by Andrew Schartmann.

All sponsored features >>

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

DISCUSSION: John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about Composers, individuals or collective?, including contributions from David Arditti, Halida Dinova, Robert McCarney and Jane Stanley.

A Splendid Achievement

FAREED CURMALLY listens to the Chamber Orchestra of the Symphony Orchestra of India

The fact that the second concert of the season announced by the Chamber Orchestra of the Symphony Orchestra of India took place at all was a minor miracle. Nay-sayers be damned, the pundits advising the state government on all matters public won the day. Exactly two weeks on from the first concert of the season, the resident chamber ensemble came together on another pleasurable Sunday afternoon of 14 November 2021. It is also a pleasurable duty to confirm that the third concert in this series did in fact take place some two weeks after this one on 2 December.

Let me pause a little to ruminate down memory lane. Just over fifty years ago, the foundation stone of the visionary project called the National Centre for the Performing Arts to enshrine the valuable and diverse art forms extant within the country was laid by then Indian Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi. 29 December 1979 would have been a red letter day with the stars' augured well for the future of this artistic endeavour. Invited guests had gathered together in the small mini-auditorium within a posh residential district of the city of Mumbai to hear two of the greatest instrumentalists of north Indian music: the world-renowned sitar maestro Ravi Shankar and his most favoured tabla player-partner Alla Rakha. At that moment in time the horizons of the new project were limited by space and technology. The committee were anxious to record and archive the great living exponents of Indian music, both vocal and instrumental, and dance. At the very most performances of theatre in English and Indian languages as well as screenings of films did take place. At least as far as western classical music was concerned there was a worthy anniversary or two celebrated in fledgling circumstances. They had performances and screenings to mark the deaths of Shostakovich and Bertolt Brecht. Beethoven's two-hundredth birth anniversary came in 1970 and invited musicians of the stature of Lord Yehudi Menuhin, his sister Hephzibah and brother-in-law Louis Kentner played the great German master's sonatas.

Some ten years on, a large plot of reclaimed land was donated by the Bombay Port Trust to the NCPA for a 99-year renewable lease. Under the leadership of several successive talented and industrious directors the sprawling five theatre arts district occupies a southern tip of coastal Mumbai. Lapping the shores of the Arabian Sea on two sides of a rectangle, it is picturesque, easily negotiable and eminently practical to attend after working hours.

Nariman Point, Mumbai, India - home to the NCPA. Photo: Suhail Kazi

The Tata theatre bears the name of the majority sponsoring family. At just over a thousand-seater it is by far the most used of the five theatres of the arts complex and was opened on 9 November 1980 with a week-long celebration. It has excellent sight lines and near-perfect acoustics. And it is the home of the more recently established Chamber Orchestra of the SOI.

In keeping with the generally optimistic and balmy air this Sunday afternoon there was some light and frothy music from the Venice-born Antonio Vivaldi to open the concert. The afternoon began with two excerpted concertos from the Op 3 L'estro armonico (Harmonic inspiration) set, first published in Amsterdam. The roughly contemporaneous German composer Johann Sebastian Bach was surprisingly less well-known in his early lifetime than was Vivaldi. The latter wrote more than five hundred violin concertos and numerous operas. Bach wrote all manner of instrumental and vocal music with the exception of opera. In their own lifetimes there was no question that Vivaldi was famous all across Europe while Bach remained quietly unknown until his rediscovery by Mendelssohn in the mid-eighteen hundreds. On this occasion two of Vivaldi's Op 3 set were performed: No 10 in B minor and No 11 in D minor. No 10 scored for four solo violins, a cello and continuo, is often played and its technical challenges remain largely insurmountable. To get four equally gifted fiddlers on one stage in fierce dialogue is rare and we are not expecting the highest standards as in the recording studio. Suffice to say, these four youngsters acquitted themselves admirably in the face of any preconceived comparisons. The soloists included two Kazakhs - one the principal violinist - and two Indians. The other Vivaldi concerto on the programme was scored for two violins, lower strings and harpsichord.

It was hardly less successful with the leader pairing up here with a student violinist.

It is chastening to know and worth remembering that although Bach's music is regarded today as the pinnacle of Baroque music, he however respected and paid homage to the music of Vivaldi by transcribing many of the senior's violin concertos for harpsichord which was Bach's own instrument.

The second half of the programme was dominated by twentieth-century English composers - namely Sir Edward Elgar and Lord Benjamin Britten.

Relinquishing the baton for the violin bow, conductor Marat Bisengaliev was beguiling in three miniatures by that quintessentially English composer who died in 1934, Edward Elgar. Marat proved to be an ideal interpreter, though sometimes wilful in dynamics and phrasing as well as unnecessary agogic devices. He did however bring a sweet tone without undue lushness, hinting at just the right tinge of melancholy in the sentiment. These miniatures he is a master at, as evinced by a successfully-reviewed CD of similar pieces by Elgar for violin published by Naxos. Today he chose Serenade (in Szigeti's arrangement), Chanson de Matin and the evergreen Salut d'Amour.

First performed in 1934, the year of Elgar's death, and conducted by the composer, the twenty-year-old Benjamin Britten's Simple Symphony is a surefire hit. It is not insubstantial, being more or less twenty minutes long and within the reach technically of most amateur orchestras. Here it received a sumptuous performance full of colour, vitality and richness of texture. It is thematically conventional yet carries the indelible stamp of maturity of a composer beyond his years.

Britten's 'Simple Symphony': Marat Bisengaliev conducting the Chamber Orchestra of the Symphony Orchestra of India

Although the main body of the concert ended with the Britten, there is a post script attached to this review. This concert was showcased with home-grown talent rubbing shoulders with their musical peers in the orchestra. During the latter part of the one-and-a-half-year lockdown, teachers and students alike have been assiduously working to achieve and maintain standards. It all came gloriously to fruition in today's programme. The addition of approximately six students, all in the string section, added noticeably to the quality and size of the sound. A few trainee musicians and students of the SOI Music Academy played alongside their mentors and teachers with the confidence usually only seen in more experienced musicians.

As if all this were not enough, there was a young soloist, barely seven years of age who played the famous slow movement from Mozart's Piano Concerto No 21, popularly known as the Elvira Madigan. This ridiculous soubriquet cannot be done away with since the music played in the soundtrack of the film with the same name is by Mozart. The young boy, Aayan Deshpande by name, managed incredibly well, in spite of the fact that he was playing the keyboard. In my opinion it was unfair not to give him a concert piano. His feet would certainly not reach the pedals and the conductor must have his own reasons for the alternative offered.

Aayan Deshpande plays Mozart, accompanied by the Chamber Orchestra of the Symphony Orchestra of India

But there was more in store for us. Not just Indian performers but a couple of Indian composers.

Kaizad Patel is a twenty-five-year-old composer whose ambition is to achieve recognition writing scores for Hollywood. He has already under his belt the soundtracks of thirty-five productions of films and Netflix movies receiving recently the Remi award for best film score given to him in Texas.

The piece written as a tribute to the thousands across the globe that lost their lives to COVID-19 was entitled In Memorial. Not wishing to quibble, it should read In Memoriam, adhering to the original Latin. It is a solemn and appropriately sombre affair. Starting with a slow-moving and expressive long line, it expands layer over layer and slowly winds up from the G string of the first solo violin to the top end in alt. It is free in structure with no apparent repetition, yet entirely tonal and approachable. In some respects it is reminiscent of Barber's Adagio for Strings. Although scored predominantly for strings there is a keyboard part and a special percussion instrument created for this piece, a metal sheet which is deployed towards the end as a solemn tolling of the bells. This very effective movement was excepted from a symphony. Here is a major talent indeed whom we are bound to hear more of.

As an encore we heard another young composer, this time a girl, Aaliya Ramakrishnan who seems barely eighteen. She graduated from the SOI Music Academy two years ago, majoring in the violin. Her four variations on the song Somewhere over the Rainbow is not just charming but ingenious as well, displaying a thorough understanding of scoring and composition.

Aaliya Ramakrishnan with Marat Bisengaliev and members of the Chamber Orchestra of the Symphony Orchestra of India

It sent the audience home whistling the cheerful tunes, happy and oblivious to the cares of the outside world. A splendid achievement and a fitting conclusion to the second of three ensemble evenings, bringing us into the Advent season with hope renewed.

Copyright © 17 December 2021

Fareed Curmally,

Mumbai, India

CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT MUMBAI

CLASSICAL MUSIC ARTICLES ABOUT INDIA