DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

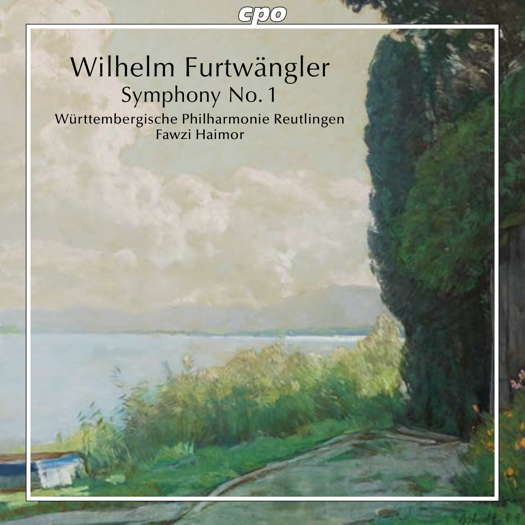

Sensitively Passionate

Furtwängler's First Symphony, heard by GERALD FENECH

'... minutely detailed and highly expressive ...'

Wilhelm Furtwängler, one of the true conducting giants of the twentieth century, was born on 25 January 1886 in Berlin. The son of an archaeologist, he studied in Munich where he was assistant (1907-09) to conductor Felix Mottl. At first he was strongly attracted to composition and, indeed, throughout his career he did write a number of pieces of a symphonic nature, but when he became director of the Mannheim Opera in 1915, he decided on becoming a full-time conductor. In 1920 he succeeded Richard Strauss as conductor of the Berlin Opera Concerts, and two years later he took over the baton from Arthur Nikisch as conductor of the Gewandhaus Concerts in Leipzig.

His other appointments included the directorship of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (1922), the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (1930), the Bayreuth Festivals (1931-32) and the Berlin State Opera (1932). He subsequently toured Europe and England with the Berlin Philharmonic, and during most of the Nazi regime his concerts were a frequent occurrence. The latter activity landed Furtwängler in hot water. Controversy arose when he led an orchestral version of Hindemith's opera Mathias der Maler in 1934, this after Hindemith had been denounced by Joseph Goebbels and the work banned.

Initially, Furtwängler resigned, but in 1935 he had a change of heart and returned to his beloved Berlin Philharmonic. Although he was offered and accepted the post of conductor of the New York Philharmonic in 1936, the hostility of American musicians to his alleged Nazi associations caused him to resign. Public sentiment also caused the cancellation of a 1949 appointment as conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, although he had been formally exonerated of accusations of Nazi complicity.

Despite this adversity, Furtwängler succeeded in forging a brilliant conducting career, and even today many renowned conductors are still under the influence of his magical baton. His interpretations were simply electrifying. As a composer he never really hit it. The main cause lies in the fact that he wrote in fits and spasms, and so his inspiration suffered from a certain want of ideas that never really wedged into a homogeneous whole.

The symphony under review is, maybe, his most successful work in the genre. Composed between 1938 and 1941, this piece clearly has Brucknerian ramifications. Indeed, Furtwängler was a huge admirer of the St Florian master, so it is no surprise that this symphony, which is satisfyingly structured, is comparably as long as, say, the 7th or 8th of his mentor.

The opening Largo - Allegro, which is a rework of a 1908 Largo, is the least impressive, but some passages are dramatically exciting, which leave the listener with a sense of anticipation for greater things.

Listen — Wilhelm Furtwängler: Largo - Allegro (Symphony No 1)

(CD1 track 1, 0:00-0:55) ℗ 2021 Classic Produktion Osnabrück :

The Scherzo is indeed delightful, and the Molto adagio, con devozione is sensitively passionate with a huge dissonance at the peak of the final 'crescendo' reminding one of Bruckner's Ninth.

Listen — Wilhelm Furtwängler: Molto adagio, con devozione (Symphony No 1)

(CD2 track 1, 16:16-17:11) ℗ 2021 Classic Produktion Osnabrück :

The final Moderato assai - Largo - Allegro is a whiff complicated but the coda, with its overwhelming cumulative power and explosive energy, is truly impressive.

Listen — Wilhelm Furtwängler: Moderato assai - Largo - Allegro (Symphony No 1)

(CD2 track 2, 28:44-29:37) ℗ 2021 Classic Produktion Osnabrück :

The conductor and orchestra are not household names, but this minutely detailed and highly expressive interpretation is a superb advert of Furtwängler's compositional skills. Maybe a fresh appraisal in this regard will not be amiss. Sound and annotations are first-rate.

Copyright © 27 August 2021

Gerald Fenech,

Gzira, Malta

CD INFORMATION - WILHELM FURTWÄNGLER: SYMPHONY NO 1