DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

DISCUSSION: What is a work? John Dante Prevedini leads a discussion about The performing artist as co-creator, including contributions from Halida Dinova, Yekaterina Lebedeva, Béla Hartmann, David Arditti and Stephen Francis Vasta.

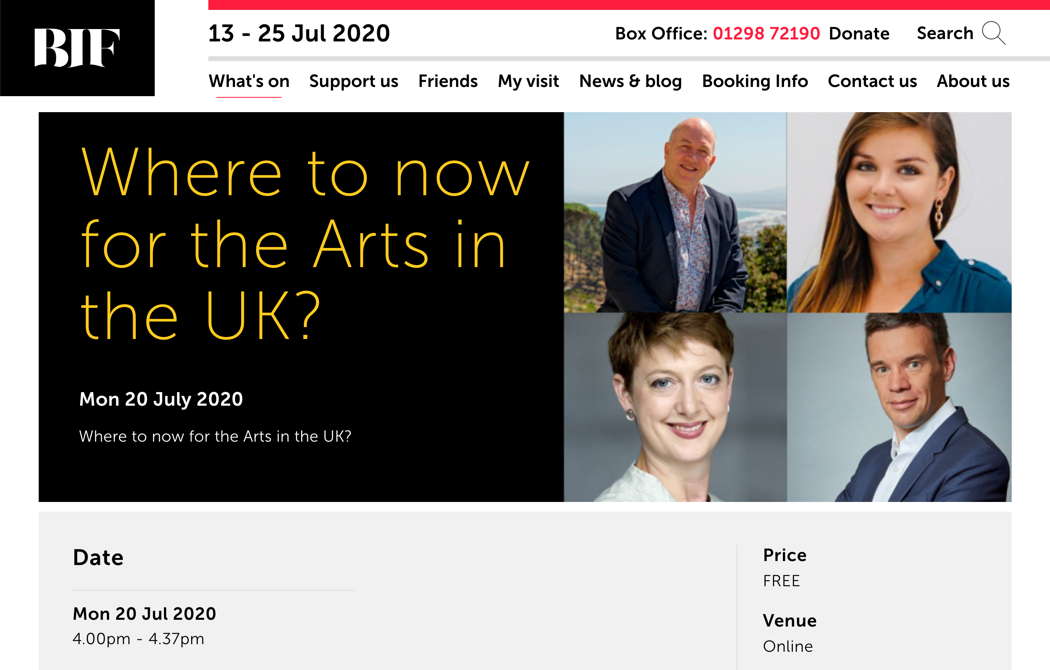

Where to now for the Arts in the UK?

Annie Lydford, Julian Glover and Emily Gottlieb in conversation with Michael Williams as part of the Buxton International Festival Digital 2020 Season, reported by MIKE WHEELER

Annie Lydford has been Chief Executive of Nevill Holt Opera, in Leicestershire, since November 2019, journalist Julian Glover is Associate Editor of the London Evening Standard, and Emily Gottlieb is Chief Executive of the National Opera Studio. 'Where now for the Arts' says the heading, but the discussion, for most of the time, focuses very much on opera.

Buxton Festival CEO Michael Williams begins by suggesting to Lydford that it must have been devastating not to have been able to deliver her first season because of the COVID-19 pandemic. She agrees, but points out it was much more so for people who have been involved in the company for years, given that everything done during the rest of the year leads up to the main summer event. Nevill Holt Opera runs an education and community programme before the summer each year: 'we had just completed a three-month spring educational tour around the Midlands, and our ability to pay for that tour really hinges on the summer festival taking place'. Different types of companies - big opera houses, tiny companies, summer opera festivals - will have been affected differently, she adds. 'We will all respond, I hope, in slightly different ways ... that bring in new ideas and new thoughts into the sector', and she looks forward to 'more choice, more diversity of thought, more diversity of persons working within the sector' - Gottlieb nods vigorously in agreement - 'and lots of different responses that ultimately make us more creative.'

Online publicity for the Buxton Festival film Where to now for the Arts in the UK?

Asked about the impact on the National Opera Studio - 'such a key institution within the opera industry', as Williams describes it - Gottlieb echoes Lydford's comments. One of the wonderful things about the sector is that there are so many different ways of working, resulting in a 'rich ecology'. The NOS has its own building, is independent, and has been relatively OK so far. It runs a nine-month training programme for young artists from all over the world which has been able to continue through online coaching. One of the opportunities has been to develop into new areas, including meetings via Zoom. Taking part from their own homes has encouraged people to be more open, honest and authentic with one another. This in turn reflects the way the audience interacts, through communication, story-telling, and authenticity. 'The digital world has enabled us to work out what that looks like in the modern age.' She also underlines the connectivity between opera companies and festivals in the UK - 'we are probably having more conversations than we ever did before' - but also internationally. The Opera Europa family of opera houses have all been talking together, and 'some really positive ways forward in terms of future communications and partnerships will come out of this.'

Williams then asks Glover about his recent interview with UK government culture secretary Oliver Dowden. Glover describes Dowden as very decent, solid, caring, honest, 'and he's landed himself in an almighty nightmare, which everybody's turning to him to sort out'. 'The government will support the arts', he assured Glover, but the question remains: will the government bail out the sector, and what does a bail-out mean? (Since the discussion was recorded, the government announced a £1.57 billion investment package for the arts in the UK.) Companies need to know not only what they can do now, but whether they will be able to cover their costs in the autumn. Dowden has to get the Treasury on board, but he realises the urgency involved. He 'understands that the arts matter in themselves, not because of what they earn'. He was himself planning to come to Buxton this summer.

Williams goes on to mention discussions among the Buxton Festival board about the feasibility of producing a festival with social distancing reduced to one metre. Lydford replies that opera is the sector best-placed to come up with 'creative, incredible, unthinkable solutions to a challenge like that', given the time and the financial resilience. Acknowledging that she is speaking for a company with very small overheads, she says that it is time to plan for next summer in terms of using the available space, and maybe re-planning the programmes.

Williams turns to Gottlieb again. Directing opera is all about touch, and singers have to get very close to one another in getting the story across, he suggests. Gottlieb echoes Lydford's point about the opera sector's creativity and resilience, but full-scale productions are going to be really challenging. 'No-one's under any illusions that there are going to be things that we can't do ... But it's not impossible at all, we'll just adapt to the situation.' She takes the opportunity to give 'a shout-out for all the freelancers' who work in opera: stage managers, technicians, wig-makers, orchestral musicians. Opera is the most collaborative of art forms, but freelancers are really hard-hit at the moment. 'We really need our freelancers, and we really need to support them at this difficult time.'

Williams refers to the recent series of recitals in London's Wigmore Hall, which saw musicians 'performing in that wonderful space to no audience'. Is it possible, he asks Glover, 'to create art without an audience present?' Glover replies that he can't say how it would feel as an artist, but he answers with a firm 'yes'. Art is about that immediate connection between creation 'and your own body and soul and feeling'. He recalls seeing Jonas Kauffman online, performing in an empty Munich opera house. 'That was live art for me. That was real.' Two people doing something in an empty space 'has a certain dramatic power' seeing the rows of empty Wigmore Hall seats. Opera on stage with no audience would feel strange, 'so we need to get back to having an audience, and that is beginning to happen in parts of the world'. Recent sporting events in New Zealand suggest a way forward. Any social distancing rule is going to be hard. It's the sense of anticipation and being part of the crowd that makes it powerful, not just the stuff on stage. We really miss the audiences, and our audiences are missing us, adds Gottlieb.

One of the challenges, says Williams, is to woo people to feel safe and secure, and asks Lydford about measures she might put in place next year. At the time of recording, NHO recently announced live performances at the end of June and early July in the gardens, with four of their young artists. NHO members were invited to the first performance, and the wider public to the second. The response, she says, has been 'phenomenal'. There is the benefit of being outside - as opposed to cramming them into a theatre like Buxton, Williams suggests - and, Lydford continues, the audience wants to hear solutions to the challenges. 'We're not going to lie to our audiences and pretend that something's safe when it isn't.' There will be restrictions in place, but the fact that so many people want to turn out 'bodes well'.

Williams reports a conversation with Paul Kerryson, Buxton Opera House's Chief Executive, who said that the board 'was working very carefully at elements of opening up the Opera House', so that by next spring a system will be in place where the audience will be able to feel comfortable with the environment. In his short time in post at the Festival, Williams says he has been 'amazed' at the audience's loyalty. 'Will there be a sense that people are defiant in making sure that opera continues in this part of the world?', he asks Glover.

'Yes. People will want to come because what they'll see is going to be fantastic.' Hopefully it will feel like a celebration, but we will also be more used to living in the post-COVID world, and will be better at judging what needs distance and what doesn't. 'The hunger for entertainment, intelligent discussion, and music will be greater than ever', and this is something for the whole country, not just the large metropolitan centres.

A screenshot from the Buxton Festival film Where to now for the Arts in the UK?

Williams concludes by reporting back from the latest Buxton Festival board meeting, which gave its full backing for next year's Festival. Deferred productions of Rossini's La Donna del Lago and Sondheim's A Little Night Music are already in the pipeline, and 85-90% of the musicians originally engaged are available; the Festival's book events, though, will be different.

He then invites the other three to give their final thoughts, and to look forward to next year. Lydford recalls how much people have said how crucial music and theatre has been during the last few months, 'and we can't wait to get back.' Gottlieb reflects on the value of time, particularly time to think: 'I would like to build in more time in my organisation, to listen to one another. And I don't want to lose the sense of connectivity and collaboration that we've built.' Much of what has been happening, says Glover, has been horrible for institutions, for infrastructure, for people. But the performers and audience are all there - we need to 'keep that hope'. By next spring, he is sure, we'll be looking back and saying 'my goodness, 2020 was bizarre, but least we're beginning to rebuild and listen and perform'.

Copyright © 4 August 2020

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: BUXTON FESTIVAL

FURTHER ARTICLES ABOUT CLASSICAL MUSIC IN THE UK