SPONSORED: Profile. A Gold Mine - Roderic Dunnett visits Birmingham to talk to John Joubert.

SPONSORED: Profile. A Gold Mine - Roderic Dunnett visits Birmingham to talk to John Joubert.

All sponsored features >>

A Connolly Smorgasbord

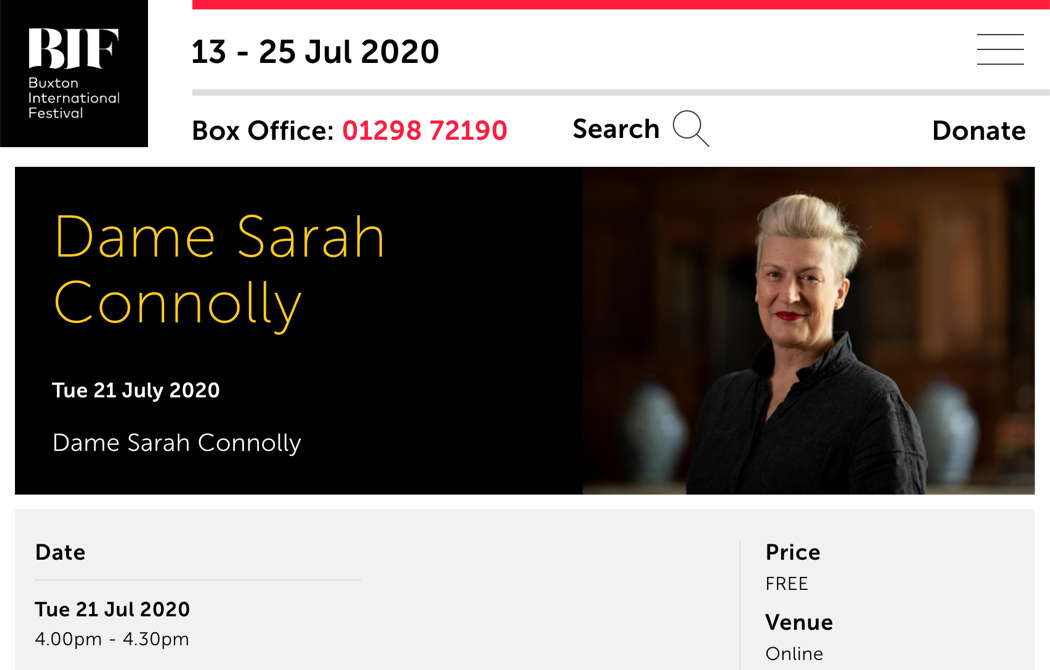

A selection of performances by Sarah Connolly, as part of the Buxton International Festival Digital 2020 Season, reviewed by MIKE WHEELER

Mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly was due to give a song recital with pianist Joseph Middleton at this year's Buxton Festival. In her charming short welcome message to this 'Connolly smorgasbord', she says how sorry she is not to be in Buxton this year, and promises to be there next year. She urges us all to stay well and wear our masks, and sends us all 'lots of love'.

A screenshot from Sarah Connolly's introduction to the BIF film

We begin with two contrasting Handel opera arias. 'Va tacito e nascosto', from Giulio Cesare in Egitto, is taken from Glyndebourne Festival's much-celebrated 2005 production, directed by David McVicar, with William Christie directing the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Caesar has stepped unwittingly into the power-struggle between Cleopatra and her brother Tolomeo, Egypt's joint rulers. When Tolomeo offers to show him round the royal apartments, he accepts, but is sure that Tolomeo is up to something. In this, one of Handel's most familiar arias, notable for its horn obbligato, Caesar is very much on his guard, comparing Tolomeo to a hunter sneaking up on his prey. Connolly's Caesar is in full command of the situation, vocally authoritative, and deftly negotiating the twists and turns of the stage movement, as he and the other characters pace the ground like so many human chess-pieces.

Connolly was reunited with McVicar and Christie, this time directing his own band, Les Arts Florissants, in November 2019, for a Vienna State Opera production of Ariodante. In 'Scherza infida', from Act II, the knight Ariodante thinks he has been betrayed by his fiancée Ginevra. This is all a plot by the villain, Polinesso, of course, and everything works out fine in the end. But for now, Ariodante wishes the faithless Ginevra joy in her lover's arms, and longs for death, but warns that his ghost will return to torment them. The sombre blue cast to the set and lighting point up Ariodante's lament perfectly, though it's sometimes too dark to see much detail. Connolly's diction and phrasing are as sharp as ever, investing words like 'infida' and 'morte' with a weight of despair, and the threatened haunting in the middle section with a kind of weary determination. The audience goes wild at the end, as well it might.

Robert Schumann's Gedichte der Königin Maria Stuart (Poems by Queen Mary Stuart), Op 135, were recorded at the Wigmore Hall, London, in March 2019, with pianist Julius Drake. The first thing that strikes you is the oddly distant-sounding acoustic. The ear adjusts, but it is disconcerting at first.

These settings of poems attributed to Mary, Queen of Scots were Schumann's last songs. Mary was a much-loved romantic heroine in nineteenth-century Europe, and Connolly balances intensity and dignity as she rides the fluctuating emotions, with Drake in sympathetic support. The poignant lament of Mary's opening farewell to France is followed by her touching prayer to Jesus after the birth of her son. The fierce scorn with which her address to Queen Elizabeth, in the third song, begins, softens convincingly by the end. Connolly and Drake are equally good at capturing the resignation in the fourth song, and Mary's cry for divine intervention in the last.

Online publicity for the Buxton Festival film Dame Sarah Connolly

We also see, but for the most part don't hear, actor Emily Berrington, whose readings, mainly from Schiller's play Mary Stuart, have been edited out, sadly (but understandably, because of their length). The one exception sees her reciting the start of a Latin prayer leading into the final song. (The full recital is available on the Wigmore Hall website.)

Connolly and Drake make a powerful case for these songs, still not as well-known as they should be, and hold out the tantalising prospect of her visit to Buxton next year.

Copyright © 7 August 2020

Mike Wheeler,

Derby UK

FURTHER INFORMATION: BUXTON FESTIVAL